Cargill wants to expand its destruction in the Amazon

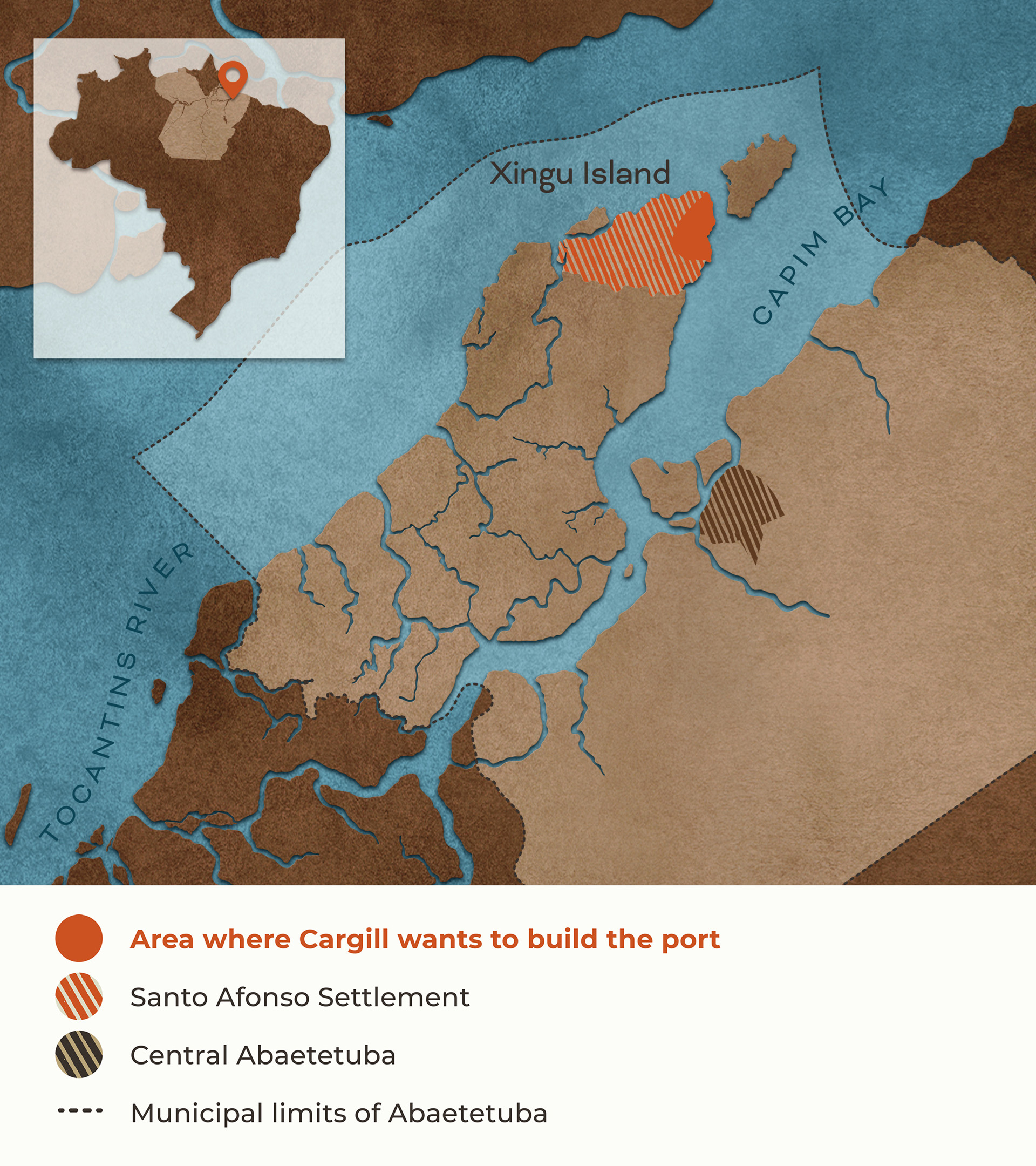

Despite failing to meet legal requirements, the U.S.-based corporation operates two ports exporting soy from Pará. Now it wants to build a third. Though the project has not yet left the drawing board, the Public Prosecutor’s Office suspects the proposed site around the Abaetetuba islands was irregularly acquired

Isabel Harari (text) and Alessandro Falco (photos), Abaetetuba/Pará – October 2, 2023

The first time Clodoaldo Santos saw soy, it was in a fish’s belly. Tucunaré, as the 53-year-old man is known, was fishing in Marapatá Bay when he came across a soggy grain in the gut of a mandi, a common catfish in the region. “This fish is better off than us, it’s even eating beans!” he joked. His brother-in-law was the one who explained to him that the bean was soy that had fallen into the river from one of the barges that transport Brazilian grains abroad. A fisherman, he was born on one of the seventy-two islands of Abaetetuba, in Pará, in the Brazilian Amazon. He learned his trade and the rhythms of the tides from his father when he was just a child, and also to recognize açaí, babaçu, and rubber tree seeds. Yet this unfamiliar, Eastern Asian legume was stealthily advancing toward his own backyard. And he would soon need to fight for the land where he was born and raised.

Ever since the U.S. multinational Cargill built two ports in the state—in the cities of Santarém, in 2003, and Miritituba, in 2017—the landscape of northern Pará has been shifting. This construction was done without consulting the traditional communities affected and, in the case of Santarém, in alleged violation of at least nine laws, conventions, and international treaties according to a report by human rights organization Terra de Direitos. The forest is languishing amidst the crops. Despite various irregularities in the two previous projects, the transnational giant plans to build a third port facility right in front of Tucunaré’s home. To do this, it will once again work outside the law and without input from affected communities. Land purchased by the company overlaps an agrarian reform settlement, a transaction that has raised red flags for the Public Prosecutor’s Office. In June, the agency filed a legal action with the Courts demanding the project be suspended and also requested a more detailed investigation by the Anti-Corruption Center due to the possible involvement of government employees.

Tucunaré, a fisherman from Abaetetuba, is confronted with the stakes raised by Cargill to demarcate the area it has bought to build a third port in the state of Pará

Tucunaré, a fisherman from Abaetetuba, is confronted with the stakes raised by Cargill to demarcate the area it has bought to build a third port in the state of ParáThe Abaetetuba islands are located at the confluence of the Tocantins and Pará Rivers, 120 kilometers from Belém. Over 7,000 families of ribeirinhos, a traditional community that lives according to the pulse of the river and the rains, call the islands home. In the dry season, they collect açaí. In the winter, when the river swells, their daily life is dominated by fish. Twenty-four agrarian reform settlements are spread across the isles, which neighbor the homes of another 700 families of quilombolas, as the members of Brazil’s Maroon communities are known.

The tide dictates the pace of life. The ebb and flow partake in a dance invisible to those who are not native to this place. But Tucunaré is from here. And he knows when to enter the river. The fisherman adjusts the boat’s motor and heads straight down the middle of the waterway that cuts through the thick plant cover. He passes by the centuries-old rubber trees he has seen since he was born and that are now surrounded by giant concrete pilings. These structures, which are foreign to the forest landscape, run along the right bank of the São José Stream and into the backyards of the community’s residents. They form a fence, delimiting the land purchased by Cargill, which may hold a future port. That is, if the company manages to once again overcome all of the barriers erected by environmental laws.

The large concrete pilings are embedded into a collective açaí grove. Already moistened and covered in algae by a forest that is attempting to take back its space, they need no barbed wire—despite the holes that are meant for them. The existence of these pilings is already effective at keeping away residents. “Most people don’t go there [anymore to get açaí] because they’re scared,” rues one fisherman from the São José community who did not want to be identified, fearing retaliation from the company.

The açaí grove is not the only communal space Cargill has fenced off. The enclosed forest spills out into a large, sunny area that is flooded and fertile: the islands’ three lakes. They are a huge nursery of fish, birds, and insects, where for generations people have collected wood for their homes and seeds for their gardens. The largest lake, Piri Grande, lies inside an area purchased by the U.S.-based giant. “They’ve already set up a boundary in the lake. If a company like that goes in there, it’s all over. Not even the animals will have peace,” laments Pedro de Alcântara, a fisherman from the Igarapé Vilar community, neighboring Piri Grande. At 80 years old, Pedro fears the lake will be destroyed to build the port.

While he prepares bait by mixing babaçu and meal and wrapping it in tururi fiber, a specialty of the fishers of Abaetetuba, Osvaldo de Sousa, or Seu Vadico, as he is known, talks about the life that could potentially disappear. “Here we catch shrimp, paraíba fish, whitefish, gilded catfish, caracids, mandubé catfish, mandi catfish, highwaterman catfish, Amazon ilisha, peacock bass, rhombic mojarra, toothless characins, mullet, pike cichlids, black ghost knifefish…” he says. On the river hours later, Vadico ties the cylindrical shrimp traps known as matapis to the pilings lining the banks of the island. When he raises his head to look forward, he sees the area Cargill has marked off as its own. The tide there changes several times a day, but Seu Vadico is well-acquainted with those shifts: he knows exactly when to pull out the matapi without getting stuck in the sandbanks when the water level is low. Knowledge that could be lost with the imposition of the port.

In an environmental impact report, Cargill admits the venture could “possibly alter the tidal dynamic” and “interfere with fishing activity.” It also states that sand will need to be dredged from the riverbed and that the piers where the vessels dock may “occasionally” affect the speed, direction, and quantity of sediment in the water. In this report, the company does not say what will happen to the lake after the port is built. Based on the plans, the terminal will include a loading system for the grain, which will be stored in metal silos with a 16.8-metric-ton capacity.

The region’s fishing community knows the impacts of the new port will go far beyond what the company states in its report. Cargill fails to mention the existence of rock outcrops, natural structures that serve as spawning and feeding grounds for fish. “The outcrop holds the fish’s food; if they destroy it, the effects on us will be huge. Those of us who live here know how many fish we catch in that area. There’s even enough for the neighbor,” says Vadico.

There are dozens of fishing spots on each of the islands. On Xingu Island alone, there are more than 56, says Deyvson Pereira Azevedo, a resident of Capim Island, which is located near the land purchased by Cargill. The ribeirinhos who live on this island, which has 120 fishing spots of its own, produce açaí, honey, pollen, and academic knowledge: Deyvson researches sustainability and traditional peoples at the University of Brasília, and he feels the study’s failure to consider the outcrops is an “omission” that aims to cause destruction.

“What the company is proposing is to fence off communal property, community forests, and cause destruction,” explains Deyvson’s brother, Hueliton Azevedo. Hueliton, who is also a coordinator in the Movement of Ribeirinhos and Ribeirinhas of the Abaetetuba Islands and Floodplains, continues: “for the vessels [loaded with soy] to pass, the outcrop has to be destroyed, but that’s not what it says in the environmental impact study. They are trying to hide any negative consequences that might hinder the project’s environmental validity.”

Residents point out the technical language in the report hides the full scope of the port terminal’s potential impacts: if built, Cargill could rob the tides of their rhythm—of their ebb and flow. Without it, the ribeirinho way of life is at risk.

In light of accounts that the report downplays the impacts, Cargill told SUMAÚMA that “the documents are under evaluation and that the company remains available to provide additional information to the competent authorities.” As regards the fence, it claimed “there is no reason for the community to be afraid to enter the area which, by the way, is not fenced or otherwise physically protected.” The transnational soy company submitted its environmental impact report to Pará’s Department of Environment and Sustainability in November 2018 and is awaiting the agency’s analysis to move forward with the port. Now it is also awaiting a court ruling.

Sunset on Ilha do Capim, in front of the area where the soya giant intends to build a port terminal for grain exports. Prosecutors suspect land grabbing

Fishermen fear that if the port terminal is built, it could destroy the areas where fish feed and reproduce

Rikelme has fun in the river, which is the source of livelihood of over 7,000 riverside families on Abaetetuba's islands

The house of Seu João, in Igarapé São José, where Cargill built a fence at the back, in an area that had been collectively used by the community

Seu Vadico knows the time of the tides well, but if the port is built, not only will the tides be altered, but also fish reproduction and the way of life of the riverside communities. In the background is the Port of Vila do Conde, in Barcarena

'It was a surprise,' says Dimaiko Marinho Freitas (next to her son, Rikelme), about the community's discovery that the multinational had bought an area on Xingu Island

Mangroves cover the beach of the area claimed by Cargill, on the Igarapé São José - the land should not have been sold, since an agrarian reform settlement was created there in 2005

‘We have no idea how it was done’

The Abaetetuba islands, where the horizon is made of river, is home not only to ribeirinhos but to the 180 families of the Santo Afonso Agroextractivist Resettlement Project. One day, in 2017, they awoke to the news that a piece of their land had been sold to Cargill. “A private area appeared, and no one knows where the documentation came from. Though we’re living in a settlement [made possible by agrarian reform], [government employees] gave authorization for the area to be ceded to Cargill. We have no idea how it was done. It was a surprise,” says Dimaiko Marinho Freitas, a member of the Igarapé Vilar community, which neighbors the area purchased by the company.

SUMAÚMA was able to see the memorandum filed by the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which states that the land was obtained irregularly and that its approval by public agencies seemed suspect. The document concludes that “there are signs of possible corruption, crimes by government officials, and misappropriation of public lands.” The report points to the irregular purchase of 359 hectares to build the port terminal in a location known as Urubueua, on Xingu Island.

It’s not easy to change the attribution of an area reserved for a specific purpose, like the Santo Afonso settlement. This is why the investigation by the Public Prosecutor’s Office is focusing not only on the soy giant but also on the conduct of employees at the Federal Property Management Department and at Brazil’s agrarian reform agency because of “clear signs of irregularities and individual conduct that may constitute misappropriation of federal public lands.”

Lurking behind the story of these 359 hectares is a network of actors—two companies, federal agencies, suspicious government employees, and Abaetetuba’s municipal government. This synchronized act reveals the complexity of public land theft, commonly known in Brazil as grilagem, one of the most common crimes in the Amazon. In 2005, before the settlement was created, the government conducted a study of the area and found no title deeds under third-party names. The land in question was federal property that had been allocated for an agrarian reform settlement.

Nearly two decades later, in 2020, Cargill purchased the land for R$ 53 million (US$ 10.7 million at the current exchange rate) from Brick Logística. Previously called KF Menezes Consultoria Logística, the company claimed to have acquired the land from a female resident of Abaetetuba in 2011, in other words, after the federal government had created the settlement. This woman had in turn purchased the area from a baker and an officer with Brazil’s Merchant Marine. The document showing this pre-2011 transaction only came to light in the last few years, according to the ribeirinhos, and was not on record with the notary public of Abaetetuba at the time of the settlement’s creation in 2005.

On Ilha do Capim (Capim Island), fishermen ‘bump into’ ferries owned by Bertolini, the outsourced company that transports Cargill’s grains

On Ilha do Capim (Capim Island), fishermen ‘bump into’ ferries owned by Bertolini, the outsourced company that transports Cargill’s grains

According to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the document submitted by Brick regarding the land purchase shows signs of being “totally precarious and lacking the minimum requirements to be considered legal.” Despite this initial land purchase document, the company asked the Federal Property Management Department to “remove” the land from the settlement in 2014. The agency fulfilled this request in 2019—with the company paying R$ 1.4 million to the federal government for the area, in a sales and emphyteusis agreement signed by Flávio Augusto Ferreira da Silva, then-superintendent of the Federal Property Management Department in Pará. As a next step, to clear the way for the port, Incra, Brazil’s agrarian reform agency would have to authorize the property’s “disappropriation“—a process used to change the purpose of a federally-owned area.

When approached by SUMAÚMA, Brick Logística stated through its attorney, Pedro Larcher Felix Alves, that the deeds of conveyance issued by the municipal government—the document that transfers ownership of a property—”allowed these private parties to register ownership of these lands in their name” and that “the property originally acquired by Brick was never occupied or used by any community.” The attorney also says that the Santo Afonso Agroextractivist Resettlement Project “never happened,” alleging that Incra did not finalize the process of allocating the land for the settlement—which includes registration with a notary public and a concession contract.

The settlement was created through a directive published in Brazil’s Official Gazette. According to Paulo Weyl, a legal adviser for Brazil’s Cáritas organization, neither of the two companies asked for this document to be canceled. Cáritas, which is connected to the Catholic Church, went to court in 2021 to request nullification of the administrative process granting the area to Cargill.

Brick belongs to Kleber Ferreira de Menezes, who served as Pará’s secretary of transportation from 2015 to 2018 under the administration of then-Governor Simão Jatene (Social Democratic Party). As a secretary in the state of Pará, Menezes was quite aware of the so-called “Northern arc logistics export corridor,” a project of federal government interest dating back to the 1990s that has plans to build grain-distribution structures that would make use of Pará’s rivers. Among them is the port in Abaetetuba. In 2016, one year after his company signed a purchase agreement with Cargill for the settlement’s area, Menezes spoke about the corridor at a seminar held by Brazil’s National Land Transport Agency in Brasília. In another PowerPoint presentation he gave in May 2017, the port in Abaetetuba is not mentioned by name, although the project’s “attractiveness and sustainability” is noted.

Pedro Larcher Felix Alves, an attorney for Brick Logística who is also an attorney for Kleber Menezes, stated that the subject of the corridor “is one of the most relevant and important to the state and has been handled by every state governor, both before Mr. Kleber held the position of secretary and after he left.”

In addition to Brick Logística’s participation, in the fifteen years that have passed between the settlement’s creation and Cargill’s purchase of the land, Abaetetuba’s municipal government has issued two deeds of transfer, at different times, for this same settlement area, which is federal property. The latest one was issued in 2016, on behalf of Brick. “How can the municipal government grant a right to an asset it does not possess?” asks Paulo Weyl, of Cáritas. “They’re forcing the issue so they can have a deed that doesn’t exist.”

THE 359 HECTARES THAT COMPROMISE CARGILL

How federal land ends up being sold to a multinational in the space of 15 years—and gets the attention of the Public Prosecutor’s Office

2005

While creating the Santo Afonso Agroextractivist Resettlement Project in Abaetetuba, in Pará, Brazil’s agrarian reform agency (Incra) conducts a study and finds no title deeds under third-party names

2011

KF Menezes 'purchases' a 359-hectare are of land that overlaps the settlement from a female resident of Abaetetuba for R$ 700,000

2012

KF Menezes hires a company to conduct an environmental study on a port in the area

2014

KF Menezes asks the Federal Property Management Department (SPU) to 'remove' a certain area meant for the settlement

2015

Cargill enters into a 'purchase and sale agreement' with KF, now called Brick Logística

2016

SPU surveys the area and determines that there 'is no demand for land title regularization,' disregarding the existence of a settlement in that location

2016/Dec

The Abaetetuba municipal government expedites a deed of conveyance, transferring the land to Brick Logística

2017/Apr

Incra confirms that the area disputed by Brick touches on the settlement but claims 'there is nothing to prevent the area from being excluded.'

2017/Oct

An environmental impact study on the port is published under the Cargill logo a month before the multinational’s 'purchase' of the land is formalized

2017/Nov

Cargill files a preliminary license request with Pará’s Department of Environment and Sustainability. The project awaits an analysis to move forward

2019

SPU agrees to remove the (settlement) area and award it to Brick, which paid the government R$ 1.4 million. All that’s left is for Incra to authorize the area’s 'disappropiation,' i.e. formalize another use for the property

2020

Brick transfers the deed to Cargill for R$ 53 million, at a 3.153% increase

2021

The settlement association and the Abaetetuba federation of rural workers put in a request to suspend the disappropriation process on the 359 hectares

2021/Jun

Incra hears the demands of the ribeirinho organizations and orders the suspension of Brick’s request pending further clarifications

2022/Feb

Ribeirinhos investigate the property’s purchase by Brick and Cargill and report the irregularities to the Public Prosecutor’s Office. In their report, they include a 2003 deed of conveyance wherein the municipal government 'sold' the property to private entities

2022

Without appending an explanation to the proceedings, Colonel Neil, then-superintendent of Incra, and current state representative for the Liberal Party, authorizes the disappropriation of that area of the property

2023/Jun

The Public Prosecutor’s Office files a legal motion to suspend the port’s installation and requests further investigation into suspected grilagem

Swipe right

Swipe right

Sources: Incra, Public Prosecutor’s Office, ribeirinho organizations, and Tatiane Rodrigues de Vasconcelo’s master’s dissertation

When questioned, Abaetetuba’s municipal government stated that the ownership processes “were based on documents that are presumed to be authentic, issued by the competent agencies.” Nevertheless, the municipal government said it sent the documents to the municipal attorney’s office, nothing that “if any defects are found in issuance of the title, the municipal government will act immediately.”

Regarding the news of Cargill’s “purchase” of the area, in 2021 the settlement’s association and the federation of rural workers of Abaetetuba asked Incra, Brazil’s agrarian reform agency, and the Federal Property Management Department to suspend the disappropriation process for the 359 hectares. INCRA granted the suspension three months later, stating the need to assess the report related to the purchase of federal land. But less than one year later, without appending any explanation to the proceedings, Neil Duarte de Souza, then-superintendent of Incra, authorized the disappropriation of that area of the property.

Colonel Neil, as he is known, was appointed superintendent of Incra in 2019 through a directive signed by Onyx Lorenzoni, then-chief of staff for President Jair Bolsonaro. The appointment was criticized at the time due to his lack of experience in the area. Colonel Neil had been a member of Pará’s Military Police force for decades and served as a representative in the state’s lower house of congress in 2014. After his time at INCRA, he was once again elected to Pará’s legislative assembly as a Liberal Party candidate. “INCRA is not investigating the case and is washing its hands. The result is a serious omission aimed at facilitating the procedure. It’s a violation of extractivist rights,” says Cáritas’s legal adviser.

When asked why he authorized the disappropriation of these areas, Colonel Neil responded that “all actions appropriate and pertinent to the case in question were adopted, based on stringent and responsible technical analyses, founded on a robust collection of documents that came from the Federal Property Management Office as well as Brick Logística Ltda and the 1st Notary Public Office of Abaetetuba/PA.”

In a statement, Incra said that it is monitoring the action brought by the Public Prosecutor’s Office, affirming that it “will establish a commission to reopen, analyze, and provide an opinion on the disappropriation process.”

The Federal Property Management Department did not respond to questioning from SUMAÚMA. Neither Flávio Augusto Ferreira nor his attorneys could be reached.

Considering the shaky documentation pertaining to the 35 hectares, the Public Prosecutor’s Office went so far as to question Cargill’s “good faith”: “Given the chain of ownership submitted for the purchase of the property in question, any claims that it acted in good faith are, at minimum, a demonstration of a level of naiveté that cannot apply to legal persons with the corporate structure of the parties under investigation,” the report said.

In a statement, Cargill said that it “did not find any irregularities in the property’s title deed” when analyzing the documents to purchase the land from Brick Logística. The company also reiterated that it does not tolerate “violations of human rights at any stage of its operations, whether in Brazil or around the world.”

If it is built, the Abaetetuba terminal will receive an investment of R$ 900 million (US$ 180 million), according to Cargill, and it will move around 2 million metric tons of grain annually. This capacity could reach 9 million metric tons—equal to eleven ships per month.

Edwiges says she’s only ‘mad’ in name (her last name, Bravo, means mad). Her granddaughter intervenes: ‘she’s mad at Cargill’

Edwiges says she’s only ‘mad’ in name (her last name, Bravo, means mad). Her granddaughter intervenes: ‘she’s mad at Cargill’The people whose lives depend on the forest are not impressed by these figures. “This land has an owner,” says Edwiges Bravo, who lives in the Igarapé Açu community, near Xingu Island. The diminutive 80-year-old woman with steady eyes raised her thirteen children by collecting açaí and catching fish and shrimp, “which is the ribeirinho way of life.” Edwiges fears that if the port is built, she will be forced out of the island where she was born. She doesn’t like the city. Once she had to go there with her daughter for an emergency and, only three days later, she couldn’t wait to get back home. She is categorical—she wants to continue living on her land: “for those who grew up here, there is no other life.” Quick to laugh and surrounded by family in her kitchen, Edwiges says that she is only “mad” in name (her last name, Bravo, means mad). Her granddaughter, listening from the back of the house, categorically intervenes: “she’s mad at Cargill!”

‘There’s no peace, not even for the dead’

The residents of the Abaetetuba islands know the new port will spell the destruction of their way of life. They’ve already seen it happen not too far from where they live.

Santarém, a city in western Pará, is Abaetetuba’s future. Cargill’s first port has been operating there for twenty years. With easy shipping access, soybean and corn fields spread like wildfire through the forest, even over sacred sites. The cemetery on the road that leads to the neighboring city of Belterra is surrounded by corn, which is planted in the off-season between soy harvests. Without fences or walls to delimit the fields, the plants have grown over the headstones. “There’s no peace, not even for the dead. If things go on like this, the bones will end up as fertilizer for the crops,” laments Joycene Nogueira Henrique, president of the Rural Workers Union of Belterra.

Soy monoculture has also exploded in the municipality of Belterra, which has a population of 18,000 and extends to the edge of BR 163, the highway that conveys Mato Grosso’s grain produce to the port terminal in Pará. Before the port opened in 2000, there were 8,000 hectares of soybean fields—the equivalent of eight soccer pitches. By 2021, the fields spanned 24,700 hectares, which is larger than the capital city of a state like Recife. “Various communities went extinct,” the union president says.

Vera Paz beach in 1983, where now stands Cargill’s port terminal. Photos: Edson Queiroz/Instituto Cultural Boanerges Sena archive

Vera Paz beach in 1983, where now stands Cargill’s port terminal. Photos: Edson Queiroz/Instituto Cultural Boanerges Sena archive

The soybean fields paint the landscape a reddish hue. In July, when SUMAÚMA visited the area, the terrain was dominated by the corn crops that are sown between each soy harvest. With no forest cover, the sun beats down on anyone who walks or bikes down the road. The heat is suffocating. The residents point to the fields and sadly explain: “This used to be cassava fields. There was a community here.”

With the arrival of Cargill, the Planalto Santareno, a plateau region that spans the municipalities of Santarém, Belterra, and Mojuí dos Campos, has become the setting of a grain rush, an onslaught accompanied by pesticide use and real estate speculation. In 2000, the median price of a hectare of land in Santarém and Belterra was R$ 50. This figure skyrocketed to R$ 2,500 in 2004 and R$ 4,000 in 2008. The monotonousness of the landscape is broken by “for sale” signs planted on the roadside.

This phenomenon illustrates how animal feed has encroached on family farmland, which is actually responsible for food production in the country. Of the 72.5 million metric tons of grain exported between January and July of this year—Brazil is the largest grain producer on the planet—70% went to China and its pig-farming operations.

“A friend of mine sold his land in the early 2000s, then came the ‘correntão’ [a deforestation method whereby two tractors drag large chains through the forest to clear everything in their path]. The forest was razed to the ground. Four years later, he couldn’t even get a plot of land half the size of his old one for the same price,” said a farmer who asked to remain anonymous. Though he has been harassed about selling his property, he has chosen to stay.

Soy fields are also expanding toward Açaizal, a village of the Munduruku people. “It’s very aggressive. We’ve lost the right to live like we used to, free. They’ve knocked down our forest, destroyed our river,” said Paulo da Silva Bezerra, the leader of Açaizal, while mounting his weed wacker to tidy the land where he grows mango, pineapple, Brazil nuts, and bananas. The route from his house to the village school is dominated by monoculture fields. The community is located in the Munduruku and Apiaká Indigenous Territory, which has yet to be officially demarcated and has been under review—one of the stages of the federal government’s official registration process—since 2018. But according to the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples, there is no timeframe for this demarcation to be approved, leaving the Munduruku people even more vulnerable to the expansion of predatory agribusiness.

Between 2000 and 2022, deforestation in Santarém, Belterra, and Mojuí dos Campos affected 208,900 hectares of land—an area almost twice the size of Rio de Janeiro—according to data SUMAÚMA requested from MapBiomas. In this period, land used to grow soybeans increased by 111,400 hectares, 59% of which was the result of new deforestation while 41% was the result of soy planted on previously deforested land.

The soy invasion in Santarém is primarily tied to Cargill’s suppliers. The international organization ClientEarth filed a formal complaint with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development citing the company’s involvement in deforestation and human rights violations in Brazil. According to ClientEarth, Cargill has not responded to questioning on the issue by human rights organization Global Witness.

“There is no evidence that Cargill has a systematic process to… monitor the risk of causing or contributing to violations,” affirms a document issued by ClientEarth, which also denounces its use of displaced deforestation. In other words, the conversion of old pastureland into soy plantations pushes the expansion of new pastureland into protected areas, triggering more deforestation and exerting pressure on traditional communities. The document in question reveals that Cargill purchased soy from suppliers who are known to participate in deforestation in the Amazon and who plant soybeans in areas located in three of Pará’s Indigenous territories—not to mention offenses committed in the Cerrado, which is home to most of Brazil’s aquifers.

Corn plantations, planted during the soybean off-season, are growing over Belterra’s cemetery – the region’s landscape has been disfigured since Cargill’s port began operating in 2003

Corn plantations, planted during the soybean off-season, are growing over Belterra’s cemetery – the region’s landscape has been disfigured since Cargill’s port began operating in 2003

Santarém: the past repeats itself

Clodoaldo may have learned about the soy invasion from looking into a fish’s belly, but for the fishers of Santarém, this is old news. For twenty years, a Cargill grain terminal in Santarém has worked night and day to transport the grain stored in three silos to ships docked on the banks of the Tapajós River. With a shipping capacity of 5 million metric tons of grain per year, the port welcomes a line of water vessels ready to be loaded.

On its website, Cargill claims the objective of the Santarém Terminal is to “collaborate with Brazilian agribusiness and with the sustainable development of the Santarém region,” a statement that contrasts with a string of complaints and legal questions made since the industrial complex’s construction in 1999.

This project subsumed Vera Paz beach, one of the main leisure areas for Santarém residents. Added to this, the terminal was installed over an archeological site containing traces of pre-Colombian occupation that date back 10,000 years, also the location of an Indigenous burial ground.

A survey conducted by the Terra de Direitos human rights organization affirms that by building the port in Santarém, Cargill breached a minimum of nine laws, conventions, and international treaties. Among these is a failure to first consult the traditional communities affected, beginning operations (in 2003) without an environmental impact study, and flouting four articles of the Brazilian constitution, which enshrines the rights of Native peoples as well as the rights of all Brazilians to health and an ecologically balanced environment.

According to Terra de Direitos, to this day, twenty years into the port terminal’s operations, Cargill has yet to conduct a study on its impacts on Indigenous and quilombola communities, nor has it started a process of free, prior, and informed consultation as laid out in Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization.

So far, 20 years after the Santarém terminal was established, Cargill has not carried out a study on the impacts on indigenous and quilombola populations

In the Boa Esperança community, the plantations are also invading the cemetery. 'They don't respect even the dead,' says Dionéia, from the rural workers' union in Santarém

The Munduruku Raimundo Nonato do Lago, founding cacique of São Francisco Cavada village, has seen his territory changed and devoured by the expansion of monoculture plantations

Archaeological artefacts found in São Francisco Cavaca village, in the Munduruku and Apiaká Indigenous Land

Besides deforestation, the soy industry is also accompanied by another problem: the indiscriminate use of pesticides

Margareth Pedroso, secretary of the Indigenous Tapajós Arapiuns Council, summarizes the situation as follows: “When I go to your house, I don’t walk in any old way, I have to ask permission.” Located in the center of the city of Santarém, the Council fights for the right to consultation and for recognition of the port’s impacts on Indigenous peoples in the area. “The company needs to conduct a study on traditional communities, meaning a study on each and every ethnic group, on top of the climate diagnosis,” insists Pedro Martins, a lawyer for Terra de Direitos. He is referring to Law nº 9.048/2020, which established the state’s policy on climate change. This measure determines it is the duty of Pará’s Department of Environment and Sustainability to “incorporate climate goals into its database and environmental licensing processes.” In August, the Public Prosecutor’s Office opened an investigation into the failure to carry out a climate diagnosis in the licensing process for Cargill’s project.

While the company refuses to examine its operations’ impacts on the climate emergency, the residents feel the effects on their skin. “We used to know when it was time to plant and harvest, if it was going to rain. Not anymore, nature’s behavior has changed radically. We’ve never seen so much deforestation in the region,” said Maria Ivete Bastos, president of the Rural Workers Union of Santarém.

In August 2020, Cargill filed to renew the operating permit for its Santarém port terminal, which was granted by the state secretary in May of last year. Martins, the lawyer for Terra de Direitos, affirmed the permit had been granted despite legislation requiring a study be conducted on the impact on Indigenous peoples. “The Department of Environment and Sustainability has allowed Cargill to operate without imposing any of the necessary obligations. Which isn’t to say the company is any less at fault.”

In May, a committee of the National Council for Human Rights visited different regions of Pará and issued a report noting an increase in deforestation, in pollution caused by pesticides, in grilagem, and in real estate speculation. Among the recommendations the committee made to public agencies is a request for the Department of Environment and Sustainability of Pará to enforce and rescind environmental permits issued to illegal occupants of the Munduruku and Apiaká territory in the Planalto Santareno and to ensure prior, free, and informed consultation before every new project.

The Department of Environment and Sustainability of Pará told SUMAÚMA that renewal of the operating permit for the Santarém port “adhered to the department’s regular administrative procedures and to existing legislation.”

Cargill echoed the sentiment, claiming that “like every environmental permit, this one came with expected conditions that were rigorously met.” Asked whether their impact studies had been adjusted to include Indigenous people, the company said, “there have been no further requests beyond the documents presented at the time of licensing.”

And yet the story keeps circling back. Close to a decade after construction of the Santarém port terminal, Cargill began building another port—this one in Miritituba—repeating the same pattern of violations. The new project was once again carried out without consulting the Munduruku people who lived in the region.

Cargill affirms the impact study conducted on the Miritituba port noted the existence of Munduruku villages in the project’s area of influence. According to the company, in April 2022, the Association of Port Terminals and Cargo Transshipment Stations in the Amazon Basin, which represents the Miritituba port terminals, came up with a preliminary work plan for the Indigenous community. The association is awaiting a response from the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples before continuing their targeted study on Indigenous Peoples and free, prior, and informed consultation.

The port operates day and night, taking the grain stored in three silos to the ships docked on the Tapajós riverfront

The port operates day and night, taking the grain stored in three silos to the ships docked on the Tapajós riverfront“The worst company in the world”

The community is resisting. In March, Eliziane Ferreira, a ribeirinha, left her food cooking on the stove when she heard that a Cargill water vessel was approaching the Caripetuba community in Abaetetuba. She got on a small boat with a few other people—mostly women—and formed a barrier to prevent the company vessel from passing.

Under the hot sun, faced with raised oars and people shouting “Get out, Cargill!” the U.S. giant’s boat had no choice but to turn around and leave. Eliziane’s lunch may have burned, but she savored a small victory.

At risk populations know that they are dealing with a giant corporation with influence in every sphere. The violations committed in Brazil, added to other problems Cargill has encountered in the United States, the Côte d’Ivoire, and Paraguay, have led the international organization Mighty Earth to name them “the worst company in the world.” Based on numbers from the past fiscal year, beginning in October 2021 and ending in October 2022, Cargill, which owns Pomarola, Pomodoro, and Elefante, boasted record-breaking revenues both in Brazil (R$ 126 billion) and around the globe (US$ 165 billion).

This is the sheer size of the shadow expanding into the backyard of a man like Tucunaré, who relies on the forest for nourishment. If the U.S. multinational’s project fails once again to be stopped and a port is built in Abaetetuba, soy will be allowed to invade not only the bellies of the fish that feed his family but also his home and the land where he was born and raised.

‘Cancer in every community’

Besides deforestation, soybean fields also bring pesticides. A study shows that glyphosate residues were found in the urine of the region’s residents

Isabel Harari (text), Alessandro Falco (photos), Abaetetuba/Pará

With soybeans come pesticides, and with pesticides, disease. Farmer Rita Correa de Miranha was harvesting black pepper when she felt an ache near her armpit. A breast cancer diagnosis soon followed. She lives in the São Jorge community, near the PA 370 highway, which connects Santarém and Uruarú, in the state of Pará. Fields of grain stretch down the other side of the highway: “It looks far away, but when they spray [the poison] over there, we can smell the stench all the way over here, our noses burn.”

The tractors spray poison under the baking sun, when the wind is strong enough to scatter pesticides across dozens of kilometers, recent studies show. When pesticides are sprayed on fields, the air can spread the poison to neighboring areas. “There’s someone with cancer in every community,” said Alda Marques da Silva from a village called São Francisco da Cavada. “My brother-in-law died, my godmother’s grandson is in the hospital, my sister has uterine cancer. There’s soybean poison everywhere.” Harvest after harvest, the fields inch closer to Munduruku territory and to other communities in the Planalto Santareno.

Diagnosed with breast cancer, Rita Correa de Miranda has finished the first chemotherapy cycle and is awaiting surgery. On the right, Felipe, Rita’s father

Diagnosed with breast cancer, Rita Correa de Miranda has finished the first chemotherapy cycle and is awaiting surgery. On the right, Felipe, Rita’s fatherIn March of this year, pesticides were sprayed on a soybean field near the Vitalina Motta School in Belterra, a town not far from Santarém, causing students and teachers to fall ill. “They’re used to it,” the school staff implied when asked whether the students were scared. After being fined more than R$ 1 million by Ibama, Brazil’s environmental protection agency, the producer moved their fields a short distance away.

It isn’t easy to show the relationship between disease and chronic exposure to pesticides, but Antônio Marcos Mota Miranda, a researcher at the Evandro Chagas Institute, affirms “it’s impossible for there to be that level of exposure without symptoms and harm to the population.” He noted the situation in Belterra, where he conducts his research, is a case of “chaos in public health.”

Another study conducted in 2019 by the University of Brasília revealed that bodies of water in Belterra, Santarém, and Mojuí do Campos had been contaminated by at least one active pesticide ingredient. Residues of glyphosate, the most commonly used pesticide on soybean fields, were also found in the residents’ urine. Glyphosate consumption accounted for 51% of the pesticides sold in the Planalto Santareno.

Diseases like uterine fibroids and cervical, breast, stomach and mouth cancer have increased since 2008, with women accounting for the majority of cases (65%), according to a doctoral thesis by a researcher at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation who investigated the impacts of soy and corn in Belterra.

Rita, the farmer, has finished her first course of chemotherapy. Surrounded by the cupuaçu trees, banana trees, and sugarcane plants in her backyard, which have probably been contaminated with pesticides, she now awaits surgery to remove the tumor.

As soybean spreads, so do the threats

Much like the soybeans in the Planalto Santareno, the harassment Maria Ivete Bastos began subtly, then grew more and more intense

Isabel Harari (text), Alessandro Falco (photos), Abaetetuba/Pará

The transformation of the Planalto Santareno landscape from Amazonian rainforest to monoculture fields reveals a gradual change in the territory’s occupation that has not always been peaceful. While fields spread across the Amazon, so do threats, encroaching on the lives of residents who report the destruction.

Maria Ivete Bastos, of the Rural Workers Union of Santarém, is one of the loudest voices to decry the violation of farmers’ rights since Cargill first arrived in the region. Because of this, she has suffered numerous threats. Much like soybeans in the Planalto Santareno, this started with subtle harassment, only to grow more and more intense: messages, a suitcase of money, gunmen outside her house, her name on a “list” of people with targets on their backs. “They want us to stop fighting, to leave the land because it already belongs to them,” she said about a conversation she had with one of the gunmen.

Ivete was riding in the passenger seat of a car the union had recently bought when she was once again threatened: “They tried to burn me with gasoline.” The episode took place in a remote community about 300 kilometers from Santarém, where more than twenty houses had been set on fire. The gunmen had left a warning: if Ivete set foot there, she would burn to death. “I dug in my heels and went to the meeting,” she said. Because the union had only bought the car recently, the armed men didn’t recognize her and she was able to get away. Ivete later found out that more houses were set on fire “with the gasoline that was meant for me.”

Though she speaks confidently about her years of struggle, she does not hide her exhaustion: “I suffered a lot psychologically, I don’t know how long I’ve cried.” In 2007, she entered a protection program for human rights defenders, where she remained for ten years. Today, though she is no longer in the protection program, she continues to report irregularities. “There will always be psychological difficulties, but no matter the hurdles, I will never give up the fight.”

The Unsustainable series is a partnership between King’s College London’s Transnational Law Institute and SUMAÚMA – Journalism from the Center of the World

Without forest, the sun punishes those who cross the Açaizal village road, belonging to the Munduruku people, on foot or by bicycle

Without forest, the sun punishes those who cross the Açaizal village road, belonging to the Munduruku people, on foot or by bicycle