Norwegian and French companies turn Barcarena into a city of environmental disasters

The Amazonian municipality has had nearly 30 accidents in two decades, 16 of them connected to Norway’s Norsk Hydro and France’s Imerys, and residents fear contamination from heavy metals and a 636% spike in cancer cases from 2000 to 2022

By Helena Palmquist and Catarina Barbosa, Barcarena/Pará* – 14 March 2024

The trees along the roadside are covered in red dust. It’s residue from bauxite, a mineral used in aluminum production. This is the first sign that Barcarena is near. The highway running from the municipality to the state’s capital of Belém, 100 kilometers away, passes between two enormous tailings ponds belonging to Norsk Hydro, a Norwegian mining company. As we move forward, dust-filled leaves start to give way to the hustle and bustle of trucks loaded with grains, ore, and cattle. On the banks of the Pará River, immense ships are crowded together in the ports and industrial smokestacks pollute the view.

A little over four decades ago, Barcarena was a small city of around 20,000 people who made a living off of small-scale farming, the forest, and fish from a clean river. It was a major producer of pineapple in the Amazon region and its white sand beaches were a popular stop for travelers heading to the capital. Today, the population has grown by six times. And in addition to Hydro, the parent company of Alunorte, the world’s largest alumina producer outside of China, the municipality is home to the world’s largest kaolinite processing plant, a white substance used in a vast range of products (like plastic, rubber, porcelain, glass, paint, pesticides, and cosmetics), run by French mining company Imerys. The city’s industrial hub has another 92 companies.

The water, air, and ground have been brutally altered. And the city now has a new statistic: since 2000, there has been one environmental disaster per year. These include everything from leaks of oil, coal, lye, acids, kaolinite and sewage, to fires in chemical storage facilities, shipwrecks in which thousands of cows drowned to death, and even a cloud of soot that blanketed one of the city’s neighborhoods.

Residents report itching, gastrointestinal issues, negative impacts on childhood development, Parkinson’s disease, and cancer. Although there are no studies proving a direct link between the diseases and the environmental disasters or to the companies’ presence in the city, data indicate the amount of heavy metals found in the bodies of some of Barcarena’s populace far exceeds what is found in people in other cities. These tests have, however, caused little reaction from the government, despite their frightening results. After each disaster, the multinational and domestic companies involved are fined for environmental crimes, but continue to operate.

“We don’t live, we survive in this place,” says Elias de Castro Rodrigues, 39. “Itching, problems with throats and stomachs, everyone complains of the same things. There are days when it’s windy and we feel the weight of the air. It smells like lye, as if we were opening up a bag of cement,” he says. Elias currently works at a meatpacking plant, after being twice driven out of the beachside communities where he lived – the first time, in the late 1980s, he had to leave his childhood home, while the second time was in 2003. Always because of the advancement of industry in the city.

Environmental crimes

The frequency of environmental disasters in Barcarena concerns residents, scholars, and some authorities. There are a variety of studies, lawsuits, agreements and commissions to try to resolve the problems subsequent to each accident. Yet nothing effective is done. The industrial hub continues to grow and the accidents are repeated.

SUMAÚMA surveyed data from four sources. According to the National Committee Defending Territories from Mining, a group formed by social and academic movements, there have been 29 environmental disasters in the municipality since 2000. While the Environmental Police of Pará said it had opened 24 inquiries to investigate 22 accidents that happened between 2003 and 2018 – some related to mining, others to port activities. A report from a Parliamentary Inquiry Commission established by Pará’s legislative assembly, which investigated environmental damages in the region in 2018, lists 25 accidents from 2000 to 2016. While the state’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary said it had issued 185 environmental fines from 2018 to 2023 to ventures in Barcarena.

Timeline of Disasters

In the past two decades, the town’s residents have dealt with 29 environmental accidents—at least seven are connected to Hydro Alunorte and nine to Imerys

2000

The shipwreck of the Miss Rondônia barge causes two million liters of oil to spill into the Pará River

2002

A coal spill in the Pará River is due to a transportation failure between a ship and the Albrás/Alunorte industrial complex, resulting in a black slick two kilometers long

2003

Two red mud spills (April and May) from Alunorte tailings ponds into the Murucupi River tinge the river red and lead to fish deaths

2003

Soot rains down on Vila do Conde, covering beaches, rivers, and houses in a black residue and causing allergic reactions and respiratory issues

2003

One of Alunorte’s caustic soda tanks explodes, contaminating the Pará River

2004

A kaolinite spill from an Imerys tailings pond contaminates the Curuperé and Dendê Rivers

2004

Soot from Alunorte pollutes beaches, rivers, and the environment

2005

The Pará River is contaminated by caustic soda from Alunorte

2006

There is an algae bloom in the Mucuraça River and at Caripi Beach

2006

The spill of a large part of an Imerys tailings pond contaminates waterways and the water table in the area around the industrial neighborhood

2007

A 200,000 m³ kaolinite spill from an Imerys tailings pond travels 19 kilometers down the Curuperé and Dendê Rivers into the Pará River, making the water unfit for human consumption

2007

Fish deaths in the Arienga River near the site of the Companhia Siderúrgica do Pará (COSIPAR)

2008

Kaolinite is spilled into the Cobras River and into the smaller Curuperé, Dendê, and São João Rivers

2008

There is an oil spill at the Petrobras facilities in Villa do Conde

2008

The Jeany Glalon XXXII tugboat shipwrecks near Furo do Arrozal, leading to an approximately 30,000-liter oil spill and an oil slick that stretches close to 17 kilometers

2009

Red mud spills from an Alunorte tailings ponds into the Murucupi River, contaminating the water and causing fish deaths, along with damages to Ribeirinho communities

2010

A soot cloud forms over the entire industrial neighborhood

2011

An Imerys pipeline containing acidic wastewater bursts, affecting the Curuperé and Dendê Rivers

2012

Kaolinite leaks for 24 hours from a crack in a pipeline between the port and the French company’s plant, contaminating the Maricá River

2014

Kaolinite spills from an Imerys tailings pond and contaminantes the Curuperé and Dendê Rivers

2015

Soybeans and cattle feces tied to agribusiness multinational Bunge are dumped into the Arrozal River around the port of Vila do Conde

2015

The Haidar, a vessel carrying 5,000 live cattle and 700 metric tons of oil, is shipwrecked at the port of Vila do Conde, contaminating and causing the closure of Vila do Conde and Beja Beaches in Abaetuba, with serious consequences to residents—still unresolved

2016

Heavy metal and urban sewage waste contaminate beaches

2016

Kaolinite spills from an Imerys tailings pond and contaminates water in the Cobras River and at Curuperé, Dendê, and São João Beaches

2016

Shipwreck of the Ciclope tugboat

2018

Wastewater from Hydro/Alunorte tailings ponds spills and covers the town in red sludge

2021

There is a fire at Imerys’s Rio Capim kaolinite plant

Swipe right

Swipe right

Sources: Report by the Parliamentary Inquiry Committee for the Pará State Legislative Assembly as well as independent research for this piece

Out of the nearly 30 environmental accidents on record in the city, at least half are related to the two multinationals operating in the region. Seven were caused by Alunorte (which was controlled by the Vale company of Brazil up until 2010, when it was bought by Norway’s Norsk Hydro) and nine by France’s Imerys.

In 2018, a leak around one of Hydro Alunorte’s tailings dams polluted the region’s waterways with waste from bauxite refining. On the night of February 17, pictures of rivers and streams tinged red began to circulate among the city’s residents and were sent to authorities. The images were astonishing. With heavy rainfall causing flooding, part of the city seemed to be immersed in the red mud.

Days later, an investigation by the Evandro Chagas Institute confirmed that bauxite tailings were found in the leak. It also contained images showing what it claimed was a clandestine pipeline draining Hydro effluents to an area containing the headwaters of the Murucupi River, which runs through the city before emptying into the Pará River. The company was fined R$ 20 million (around U$ 4 million) by Ibama, Brazil’s environmental regulator, and R$ 33.4 million (nearly U$ 6.7 million) by Pará’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary. One of its tailings ponds, where the waste is alleged to have overflowed, was embargoed. The Norsk Hydro group, in which the Norwegian government holds a stake and which had net earnings in 2022 of 24.15 billion Norwegian kroner (R$ 11.4 billion or U$ 2.3 billion), denies responsibility and maintains there was just an overflow of river water brought about by excessive rainfall.

Three years later, on a night in December 2021, a strong blast followed by a bright flash announced a new environmental disaster. A fire in French mining company Imerys’s facilities released a cloud of smoke that engulfed the surrounding area. Residents in neighboring communities were terrified by the flames, with no idea whether to flee or stay home to try to dissipate the smoke. “We couldn’t even breathe, we started to get headaches. We didn’t know what to do, where to go. We tried turning on the fan to get rid of the smoke in the house. It was suffocating,” said one resident at a court hearing last October 10. After the episode, residents said they felt itchy and were coughing for days. Two months pregnant the night of the fire, the same resident said she was itchy for weeks and says her baby was born prematurely at seven months. After the incident, residents reported coughing that lasted for days, as well as skin issues.

The court hearing SUMAÚMA had access to is part of one of over 30 suits filed by Juliana Oliveira, an attorney with the Office of the Public Defender of Pará, asking for compensation for physical and mental damages for each person affected. The Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará is also suing the French mining company in a civil public action. According to preliminary findings from the two offices, the damage was caused because of deficient storage and handling of a chemical product called sodium dithionite, or sodium hydrosulfite, used to remove impurities from kaolinite. “This product generates endogenous intoxication; in other words, poisoning. The fire occurred around 7:00 PM and people didn’t know what to do. They spent the night in fear,” the public defender says.

Prior to this, kaolinite frequently leaked into the city’s rivers and streams. From 2004 to 2016 there were at least six leaks, leading the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará to file suit with the courts in 2014, asking for an embargo on Imerys pond. At the time, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office said its appeal to the courts was based on the mining company’s insistence that it would “not take responsibility for the leaks” and that expert assessments this office and the Evandro Chagas Institute had carried out indicated environmental damages were more widespread than the French company had admitted.

This suit was converted to a Conduct Modification Agreement that the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará says was fulfilled – while the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office said it “is being fulfilled.”

One of the points in the agreement called for Imerys to carry out an assessment to evaluate the “water quality of the Curuperé and Dendê Rivers and of groundwater around the ponds, to identify and quantify any impacts resulting from kaolinite leaks, while also pointing to possible remedial measures to be adopted, if applicable.”

Imerys stated that the study was done and concluded no contamination.” However, the report does not say which rivers analyzed were not contaminated. Of the 360 analyses done at different points in Barcarena, the levels for 94 exceeded the reference amounts for different heavy metals – including manganese, aluminum, and iron. In its final considerations, the report says, “it could be deduced that the occurrences of compounds in excess of legal standards cannot be related to the leaks of kaolinite waste from Imerys that occurred in the past.” The report provides two reasons for this: one is that similar conditions were identified on the Guajará-Beija River, in the neighboring municipality of Abaetetuba, and the other is “because there are studies indicating that identification of these compounds can be associated with the geogenic [physical] characteristics of the area.”

Simone Pereira, who holds a PhD in Chemistry and is a professor at the Federal University of Pará, looked at the study at SUMAÚMA’s request. She was categorical in her conclusion. “Maybe the anomalous presence of elements like lead, aluminum, iron, and manganese are associated in part with natural occurrences, but it also can’t be said that their source is not connected to human activity. Nothing can be said without a more in-depth study on the composition of waste and effluents coming from the industrial processes in this place.” She adds that she studied the region’s rivers in 2007 and found the pollution of Barcarena’s water after the leaks ended up contaminating the Pará river basin and the surrounding area, including bodies of water in Abaetetuba, because of tidal movements. “It’s common to have iron and aluminum in the Amazon’s rivers at concentrations that do not meet the legal limits, but not at the levels found in the areas affected by the leaks of Barcarena’s industries,” she says. The researcher also questions why there was no analysis of barium, a toxic element directly associated with kaolinite and normally found in very high concentrations in Imerys’s effluent. She says that although barium is not carcinogenic, it is an environmentally important contaminant.

History teacher Roberto Anjos lives in one of the most affected regions of the city, in the Curuperé community, right behind the French mining company’s tailings pond. “There are businesses everywhere, but there’s no paving, no sewerage, nothing. And the pollution?” he criticizes. His wife, activist Eunicéia Fernandes Rodrigues, routinely feels the effects of the contamination. “The company says the kaolinite is found in nature and is not a contaminant. But what about the products they add to make the kaolinite odorless, whiter?” she asks.

Eunicéia says there have been many times when she has seen the stream’s water turn green – the river’s original color is brown. “The fish are all floating, dead,” she recalls. “The state’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary comes and says everything’s OK. But we know this isn’t the natural color. Now we avoid using the water from our rivers,” she says ruefully.

With each environmental disaster in the city, the story is repeated. The population endures the immediate impacts of the leak in the rivers, they go without any access to water, and their livelihoods are hurt. Environmental agencies and the Civil Defense are called, a police investigation begins, technical investigations are done, and emergency assistance is brought in, providing drinking water, for instance, or compensatory funds for those directly affected. “During an episode, there is an immediate effort to provide support, but we don’t have permanent backing to demand health actions, because we don’t have an epidemiological study that determines the causal relationship between the [residents’] health problems and the companies’ activities,” says Renato Belini, a prosecutor working in the city who follows court proceedings on the disasters.

Without proof, simply inferring any relationship between the contamination and illnesses can also make anyone who tells their side of the story into a target. For example, in 2019 Hydro sued Marcelo de Oliveira Lima, a researcher connected to the Evandro Chagas Institute, for defamation. He had coordinated the team that assessed the environmental damages and risks to health resulting from the effluent leak in the 2018 disaster. The company lost its case, with the judge stating in his ruling that the government employee was just doing his job “of informing the population about events occurring in Barcarena.”

Glória is one of the people who fear reprisal. That is why her real name is not being used in this story. The dirt road where she lives in Barcarena is covered in reddish gravel and is located in a small community near the Hydro Alunorte industrial plant. From 2010 to 2023, she lost six family members to different types of cancer: stomach, leukemia, cervical, and now an uncle is anxiously awaiting the results of a biopsy to see if he has thyroid cancer. Next to her is a family member, Maria, also a pseudonym, who is undergoing cancer treatment and who has, in this same period, lost a brother and a nephew to the disease.

Since December 2018, they have both received bottled water from Hydro as part of a Conduct Modification Agreement signed by the company as a result of the tailings leak of 2018. They used to get water from a well, which they said was contaminated by the disaster. “It was a struggle for us to be able to receive this water, I had to fight a lot of people.”

Neither Glória nor Maria can explain why their two families have so many cases of cancer. “Could it be the water, the soil, the air?” Glória wonders. “We know so many people with this disease that it seems like everyone has it. I remember that in one street up there were three kids with lung cancer. Their mom always walked with them to hearings in the city, but I haven’t seen them for a while. I don’t know if they died or left,” she says.

For a decade, Marilza Pereira dos Santos, 69, has fought colon and cervical cancer, forcing her to undergo 37 radiotherapies, five chemotherapies, and six brachytherapies. “Suspicious, people say they’re related, that there have never been so many people with cancer, but how can it be proven? I was healthy as a horse and now I’m like this. I know a lot of people with cancer: stomach, skin, cervical, leukemia… Unfortunately, most have died,” she says sadly. When she and her husband Francisco came to Barcarena in 1992, the situation in the city was completely different. “Imagine a place where fish are abundant. The earth? Perfect for planting. Today it’s all contaminated, the water, the air, everything,” vents Francisco.

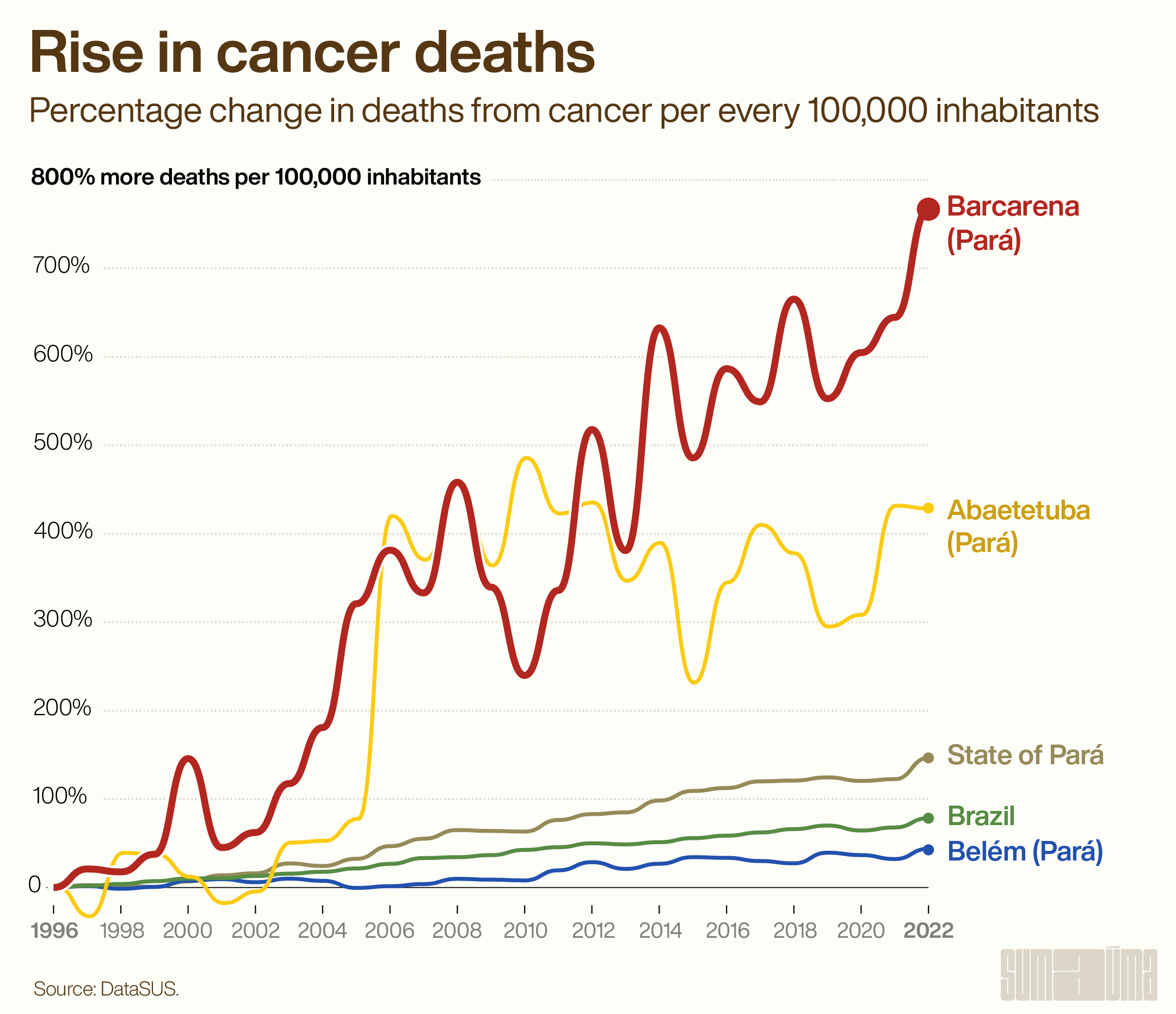

Data collected by SUMAÚMA from the Health Ministry’s Datasus system, which contains epidemiological information, provides evidence of what Glória and Marilza have noticed. From 2000 to 2022, the latest figures available, the number of cancer deaths in Barcarena grew by 636% – a rate exceeding by far the increase in population, which was 100%. For example, over this same 22-year period, deaths from cancer in Brazil rose 102% (the population grew by 20%); in the state of Pará, they climbed 225% (with a 31% increase in population), while the capital city of Belém saw them rise by 52% (with 2% population growth).

In the neighboring city of Abaetetuba, where the population expanded by 33% during this time, the number of deaths from cancer shot up 571%. The municipality, less than 50 kilometers from Barcarena, is also enduring the effects of pollution from companies operating in the neighboring territory. A study by the Evandro Chagas Institute showed the red mud caused by the accident at Norway’s Hydro mining company in 2018 also contaminated Abaetetuba’s rivers and streams with toxic metals. The assessment showed the levels of substances like arsenic, lead, cobalt, and copper found in the water exceeded the limits set by Brazil’s National Environment Council as acceptable for human health.

Ubirani Otero, with the Environment, Labor, and Cancer Technical Area at the National Cancer Institute, thinks care is required when making a direct association between the pollution and cancer cases, since cancer is a multifactorial disease. He says more in-depth studies and statistics are needed – such as taking into account the aging of the population and some issues of gender. Yet he also emphasizes that “the heavy metals, practically all of them, have already been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [under the World Health Organization] as carcinogenic or potentially carcinogenic” and he sent SUMAÚMA four scientific studies on the subject.

One of them, published in June 2021 by researchers at universities in Feira de Santana, Bahia, offers a review of academic literature and states there is usually a relationship between contamination from heavy metals and carcinogenic processes. “Even in low concentrations, extreme exposure to heavy metals promotes chronic inflammation, which triggers oxidative stress and, subsequently, the carcinogenesis process,” reads the text. “The main metals involved in the carcinogenesis process include: copper, mercury, cobalt, nickel, cadmium, chromium, arsenic, silver, and lead,” the scientific paper reports.

Some of these heavy metals are found in amounts exceeding recommendations in Barcarena’s water and its residents’ hair. Simone Pereira, a professor at the Federal University of Pará who ran testing in 2014 and 2015, sees what is happening in the municipality as a “calamity.” Tests done on tap water, the water that people drink, showed lead amounts exceeding the limits legally set by the Health Ministry (which is 10 micrograms per liter) in 90% of samples. Other toxic elements were also over maximum limits. according to the Study on Resident Drinking Water Quality in the Municipality of Barcarena. “Lead is carcinogenic, it causes a disease called saturnism, which is lead poisoning, damaging the central nervous system, and it can lead to death,” says the researcher, who is also the coordinator of the Analytic and Environmental Chemistry Laboratory.

Hair was tested from 90 people living in 11 communities in the region. Contamination levels in Barcarena are dozens of times higher than in 11 cities in Brazil, Bolivia, Canada, China, Italy, the Philippines, Spain, and Taiwan, according to a study published in November 2022. Manganese concentrations were 3.039% over the average, for nickel they were 831% higher, lead was 766% above the average, and zinc exceeded it by 160%. All of these metals likely originated, according to the publication, from activities in Barcarena’s industrial hub.

The metals are considered toxic, to varying degrees. Chromium is associated with high blood pressure, skin infections, respiratory issues, and hepatitis. Manganese, a neurotoxin, causes neurobehavioral disorders, as well as symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease. Nickel can cause lung, laryngeal, and nasal cancer. Lead is recognized by the World Health Organization as one of the most toxic metals to human health and it can, in small quantities, have neurotoxic effects on children, damaging memory and even leading to coma. Finally, excessive amounts of zinc, an essential element for a functioning human body, can lead to heart disease, anemia, gastrointestinal problems, cramping, nausea, vomiting, and damage to the pancreas.

The scientist explains that the most accurate exam when measuring public health risks would be blood tests. In 2018, at the request of the mayor of Barcarena, the Central Laboratory of the State of Pará ran such tests. However, residents who talked to SUMAÚMA said they were never given the results or, when they were, the document had erasures and was illegible.

When asked to respond, the Office of the Health Secretary of Pará, which is responsible for the laboratory, said the results were delivered to the municipal government of Barcarena and to the Office of the Municipal Health Secretary, which are responsible for forwarding them.

After three attempts to contact the city’s government by e-mail and by telephone, no response was provided as to whether the results were received and, if they were, why they were not given to residents.

New chapters may unfold in the controversy over these blood tests, since the Association of Caboclo, Indigenous, and Quilombola Communities of the Amazon (Caniquiama) has filed a lawsuit to force Hydro to perform this type of testing on the affected population. Pará’s courts have already ruled in favor of the association, yet the case remains under consideration following successive appeals by the company.

In addition to the two European mining companies, the city along the banks of the Pará River has an industrial hub with another 92 companies and two port terminals. Photo: João Laet/SUMAÚMA

Maria periodically receives bottled water from Hydro because of the mining company’s tailings pond leak in 2018. Photo: Christian Braga/SUMAÚMA

The shore in Barcarena, a place that was a seaside resort four decades ago is now overrun with ships exporting corn, soybeans, ore, and live cattle. Photo: Christian Braga/SUMAÚMA

Luiz Rodrigues has been uprooted twice because of the industrial hub; although today he lives far from the river, he keeps his fishing boat in the stream behind his house. Photo: João Laet/SUMAÚMA

The Haidar sunk in 2015, killing around 5,000 live cattle; the hull still sits off of Barcarena’s shores. Photo: João Laet/SUMAÚMA

A home located in the Vila Nova community, in Itupanema, Barcarena, one of those affected by the Hydro spill in 2018. Photo: Christian Braga/SUMAÚMA

Elias gathers açaí in the yard of his home, but he says the earth is no longer good for growing; the city used to be a major pineapple and peach palm producer. Photo: João Laet/SUMAÚMA

From seaside resort to toxic city

Barcarena’s transformation from a seaside resort and territory with traditional communities to an industrial and mining hub began at the end of Brazil’s business-military dictatorship (1964-1985), in the 1980s, with a variety of people being driven out to make room for the companies. These forced removals created land conflicts that have lasted to the present day. The state government’s public agencies which promoted these expropriations – the Economic Development Company of Pará and its predecessor, the Industrial Development Company – are fighting the communities in the courts over these lands.

In 1985, in the wake of the dictatorship’s big projects for the Amazon, Albrás, a metal production facility making primary aluminum, opened in Barcarena. Work started on installing the city’s industrial hub that same decade. The Alunorte alumina refinery was opened ten years later.

In 2010, the two European multinationals – Hydro and Imerys – respectively began to control Albrás/Alunorte and Pará Pigmentos, undertaking a social and environmental liability that had been growing since the dictatorship. Even today the industrial hub still lacks the appropriate environmental licensing, as acknowledged by Pará’s Environment and Sustainability Secretary.

When asked for a response from SUMAÚMA, Hydro Alunorte stated that “after heavy rainfall in February 2018, over 90 inspections were done by public entities and all confirmed that there was no spillage from Alunorte ponds or solid waste storage areas” and that “there are no signs of environmental damages or damages to people in the surrounding local communities” caused by the incident.

In a statement, Imerys said “some incidents occurred in recent years” and the company had since reinforced tailings pond and slurry pipeline structures. The French mining company also said that “it’s important to remember that kaolinite is an inert and non-hazardous material.”

‘Death is what we reap’

Maria do Socorro Costa da Silva is Barcarena’s most recognized community leader, because of her historical fight to recognize the rights of Quilombolas, the descendents of rebel slaves, to territories in the region. Socorro says “Hydro carries out its projects on land that has ancestry and inhabitants.” The Quilombola community where she lives, São Sebastião de Burajuba, was recognized by the Palmares Cultural Foundation and is awaiting a title deed. Today, Socorro de Burajuba, as she is known, fights to receive indemnities for the harm to health caused by the industrial activities in the region. She is one of the leaders of the Cainquiama, the Association of Caboclo, Indigenous, and Quilombola Communities of the Amazon, which filed a lawsuit against Hydro with courts in the Netherlands in 2021. A Rotterdam court has agreed to hear the case, but it is being tried under seal. Socorro and the Cainquiama are seeking compensation for damages to the property and health of 40,000 people.

Engaged in multiple struggles over land and the environment, Socorro’s life is currently being threatened and she had to be placed in a program that protects human rights defenders.

In 2023, on All Souls’ Day, in a tradition common to many cities in the Amazonian hinterlands, hundreds of people gathered in the Barcarena cemetery to honor their dead. The air was filled with the smell of burning wax from candles, while workers moved between tombs selling buckets of sand and coats of paint for gravestones. Socorro had gone to visit the grave of her husband, Raimundo Amorim Barros, who died in 2021. “This is the earnings, the compensation from the big enterprises. Death is what we reap,” she said, pointing to the grave of her former spouse, still missing its headstone.

The community leader does not place direct blame on the industrial activity for his or other people’s deaths, because drawing a direct line would depend on a more in-depth investigation that, despite so many years of fighting, they have not yet been able to do. Yet she raises questions about the public health policy related to the contamination problems. “I could have taken my husband to a toxicologist if I had received the tests they did on him,” she says, referring to the results of the 2018 blood tests that were never delivered. “They’re guilty of this. I will fight tirelessly for the government of Pará to bring toxicologists to Barcarena. I lost my husband, I lost my river, I can no longer fish, look at what is left for us from this haphazard development.”

The Office of the Health Secretary of Pará said “the results were delivered to the municipal government and the Office of the Municipal Health Secretary, which are responsible for forwarding the results.” When asked by email, the municipal government did not explain why the people examined have yet to receive their test results.

Lawsuit flood, ruling drought

Stuck between pollution and environmental disasters, the residents of Barcarena have gained allies, but they have come up against the sluggish Brazilian court system. Lawsuits related to environmental disasters, the contamination of water and people, and the removal of communities in the 1980s have been brought by the State Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, and the State Office of the Public Defender. SUMAÚMA asked the Court of Appeals and the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará if any final judgments had been rendered for the company or its executives, but received no response. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office confirmed the lawsuits have either become Conduct Modification Agreements or are awaiting a ruling.

The deluge of lawsuits, the drought of convictions, and the sluggish courts have brought another phenomenon to Barcarena: a profusion of so-called Conduct Modification Agreements, extrajudicial instruments that let faster measures be implemented to resolve problems, but that in some situations end up paralyzing legal actions and taking longer than expected to execute.

In the agreement signed by Hydro in relation to the 2018 accident, it was placed under a mandate to support livelihoods in affected communities by investing a total of R$ 65 million (a little over U$ 13 million) and by funding a series of studies. However, an analysis on the safety of the dams was only ready five years after the disaster. While socioeconomic and ethnographic studies are still in the staff hiring phase – and the environmental study has progressed to technical assessment of proposals, according to the latest meeting minutes on the agreement’s oversight. There are also plans to invest funds in implementing alternative systems to treat and distribute drinking water and to defray costs for a clinical care and laboratory evaluation system for the people affected by the accident – measures that have yet to be implemented.

Both the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará confirmed to SUMAÚMA that Hydro is complying with the Conduct Modification Agreement and that it could result in important studies to improve the problems in Barcarena. The Norwegian mining company told SUMAÚMA that “execution of commitments is monitored by a technical committee,” which is made up of representatives of the residents and organizations involved with the matter.

There is, however, a disadvantage to this type of agreement. “Conduct Modification Agreements are a faster way to resolve a serious matter. We don’t depend on a lawsuit, which always takes longer. But there is this negative effect. To enter into the agreement, there need to be reciprocal concessions and, from the side of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, we forgo the lawsuits filed,” explains Renato Belini, a prosecutor working in the city. “We allow the Conduct Modification Agreement to include that the companies are not culpable for what happened, so the scientific reports, the analyses done by experts, it all loses its usefulness. It’s a tough situation because we want to make the agreement to be able to take care of people as quickly as possible,” the prosecutor says.

Federal prosecutor Bruno Valente sees it similarly. “It’s hard to get fast results in the courts, and this ends up factoring into the equation. If the legal proceedings were more effective, it would change the correlation of forces,” explains Valente, who followed some of the environmental accidents and land conflicts in Barcarena from 2011 to 2015.

After the events of 2018, a Parliamentary Inquiry Commission was established by the state of Pará’s Legislative Assembly, which recommended 48 measures to control the situation in Barcarena, some directed at the company and others at the State Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary, which is responsible for authorizing and overseeing the industrial hub. One of the recommendations was made to the Norwegian Corporate Governance Board, a body enforcing good practices at Norwegian companies, so Hydro’s activities in Pará would be investigated.

Another conduct modification agreement, executed in 2016 between the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará and the government of Pará, stipulated the Economic Development Company of Pará and the State Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary would be responsible for a series of studies and diagnoses related to pollution and social impacts, by holding public hearings, promoting monitoring and, finally, fully licensing the industrial district. The government has still not fulfilled this commitment.

Federal prosecutor Bruno Valente feels the lack of full licensing for the industrial hub is a serious irregularity – only individual licenses are currently given to each company. Another federal prosecutor, Igor Goettenauer, who is currently handling the investigations into Barcarena within the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, makes a similar assessment. “These various economic enterprises form a synergy among themselves, so a joint license is needed, for the whole district,” he says. For Goettenauer, issuing environmental licenses company by company, regarding it as if it were an isolated impact, is part of the problem. “A structural view is needed, that considers the synergy of the different environmental impacts,” he states.

The State Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary said, “the environmental licensing process for the Barcarena industrial hub is still ongoing and is currently in the phase of drafting Terms of Reference for environmental studies and plans.”

Public defender Andreia Barreto feels there is also a problem with the licensing for Hydro’s slurry pipeline, which crosses the Quilombola communities of Jambuaçu, Nova Betel, and Amarqualta, in the municipalities of Moju, Tomé-Açu, and Acará, Pará. According to the defender, the company has an irregular license because no studies were done, nor was there prior consultation of the communities affected in the state’s interior when the structure was built. “Because there were no studies on the impacts to these communities, there is neither compensation, nor mitigation,” criticizes Andreia.

In a statement sent to SUMAÚMA, Hydro said the slurry pipeline passed through every stage of licensing established by law. “Although its installation and startup on its operations preceded ministerial directive 60/2015 [which stipulated the need to consult traditional communities], the company is carrying out the Quilombola Component Study and the Quilombola Basic Environmental Plan in all of the communities located in its area of influence, as established in the norm.”

Each time a colleague dies, Socorro calls for three days of mourning, closing the doors of the association she coordinates and sending comforting messages to those they knew. “It hasn’t been easy. Here in the Burajuba Quilombola community and in other communities, our lives are spent holding wakes, going to the cemetery with the deceased,” she laments. “People call it development, I call it a slow death. Every day we die a little bit. We just want to live, but it’s hard.”

*Álvaro Justen contributed reporting

‘If you don’t leave, the tractor will run you over’

The displacement of traditional communities to make way for industry and mining companies started during Brazil’s business-military dictatorship – and continues to this day

By Helena Palmquist (text) and João Laet (photos), Barcarena/Pará

In addition to health problems and the loss of a traditional way of life, dispossession is a common topic in conversations with residents in the Barcarena region. According to public defender Andreia Barreto, these forced removals, which began in the 1980s and have been carried out without compensation or respect for collective rights, have become a struggle that involves reclaiming these territories, even as European mining giants file for eviction.

Carlos Espíndola, 53, remembers the moment, at the end of the business-military dictatorship (1964-1985), when the police informed his aunt that everyone in the Tauá region would have to leave. He was only 12 years old. “‘If you don’t vacate your house, the tractor will run you over.’ And she turned to my uncle Castanha and said, ‘Castanha, aren’t you going to say anything?’ He was a big man. But he kept quiet. Can you imagine living on the land where you were born and raised and suddenly being told you have to leave or a machine will run you over?” he asks. Carlos says they were given 15 days to move to a small house with a bedroom and living room in a faraway neighborhood built by the Industrial Development Company. “Uncle Castanha was a strong man, but he fell into a depression. He didn’t make it. He died.”

After more than three decades of longing and struggle, in 2016 Carlos joined forces with his former neighbors and, together, they decided to take back the land where they were born. “There are 182 families, and that land is ours,” he affirms. Before this, he worked as a builder and hotdog vendor. But his dream was always to go back to working the land. Today, in Tauá, Carlos and other residents grow large quantities of cassava, flour, Brazil nuts, açaí, and several fruit varieties.

This region, which for years sat beside one of Hydro’s tailing ponds, was subject to unregulated, illegal logging. Yet, the moment the families returned, the company alleged it owned the land and the farmers would destroy the nature reserve. Pará’s courts granted a repossession order to Hydro and, according to residents, in 2017, police officers once again evicted the families and destroyed the small farms, bridges, and shacks they had slowly been building. The following year, the families returned.

They recovered their land in response to a decades-long lawsuit. Since 1989, 450 people, including several families from Tauá, have been suing the Pará and Barcarena Industrial Development Companies, both responsible for displacing residents from the area, for damages. There have been rulings for and against the residents, but in 2014, the lawsuit was stayed, and to date they have not been compensated.

Although there is a lingering fear of new evictions and environmental disasters, the abundant harvests and joy of returning to their land keep the community vibrant. Manoel Raimundo Furtado Dias, aged 71 and nicknamed Lambreta—or scooter—for his light-footedness, is the group’s elder. His umbilical cord is buried at the foot of a tree there. “We don’t regret a thing. When we were evicted, all we did was cry, so many people died, including my father, who was still talking about Tauá on his deathbed. He died of sadness from being evicted.”

Even though it’s very close to one of Hydro’s tailing ponds, Tauá is a place whose forests are still conserved. There are dozens of fruit trees, and residents are proud to subsist on them. The bridges and roads that were razed when they were evicted in 2017 have been rebuilt. When the news team arrived at the community, they were in the midst of building the Ulisses Manaças Community School—named in honor of the leader of Pará’s Landless Workers’ Movement. They were also constructing another building where they planned to hold meetings to draft protocols for prior consultation, discuss problems, or simply chat about local history.

The Economic Development Company of Pará told SUMAÚMA , “the information about the eviction of residential communities from areas belonging to the Barcarena Industrial District is without merit, and the company has always recognized the legitimacy of these communities and their rights, including their decision to leave their property when offered compensation calculated on the basis of appraisals drawn up according to criteria and requirements determined by governmental bodies.” The Economic Development Company of Pará affirmed that “residents only leave their property in the Industrial District after negotiations have concluded and been formally accepted by the families in question.”

A similar story is, however, unfolding across seven Barcarena communities visited by SUMAÚMA: people are being removed from their property without compensation, residents are being evicted, attempts are being made to take back the land, and there are lawsuits that demand travel to and from Court.

In September 2021, Imerys was ordered to pay damages to the Dom Manuel community, evicted from their property to make way for construction of the tailings pond for the company’s kaolinite processing waste. A Pará trial court ruled that the company had engaged in dispossession—in other words, it had unduly evicted the residents—and had caused damages to the community. In August 2023, the appeals court upheld this sentence. Because the territory is contaminated with industrial waste, it cannot be returned to residents, and the courts will have to determine how much compensation is due.

Neighboring the bygone Dom Manuel community, and living in the shadow of the Hydro’s tailings pond, the residents of Curuperé—where the house of teacher Roberto Anjos and activist Eunicéia Fernandes Rodrigues is located—fear they will be next. Andreia Barreto wants to ensure no more rights are violated and has filed another lawsuit with the Castanhal Agrarian Court asking that the Economic Development Company of Pará not expropriate the area unless minimum requirements are met. Among these is the option to resettle, fulfillment of prior consultation, and prior assessment of improvements.

According to the lawsuit, seven years after the agreement was signed, the company continues to harass families, entering communities and advising people not to improve their houses or farmland because they will not be compensated for these updates in the event they are expropriated. If the Court agrees with the public defender’s allegations, these violations would need to cease immediately. Until then, the fate of the Curuperé community may be the same as that of countless others in Barcarena: families who had lived on the same land for generations and taken part in a traditional way of life have lost their homes and been separated, unable to reproduce their former ways of living.

A different passion

The trauma of these displacements has led to a curious term—one related to the word paixão or “passion”—to crop up in conversation with interviewees. “He became impassioned,” “she was very impassioned and died,” “my mother was so impassioned that she withered away.” The use of this word to describe the suffering people from Barcarena feel due to industrialization probably has the same meaning as in the expression “the passion of Christ.” It comes from the Latin word passio, which means suffering.

“These days we say someone’s depressed, but back then we used to say they were impassioned. In the 1980s, a wave of suicides hit the town when construction started. Because people couldn’t come to terms [with the change to their way of life]. They were used to living in the backcountry, the forest. Then these companies arrived and kicked everyone out,” says Sandra Amorim, a leader of the Sítio São João quilombo, a community of descendants of enslaved Africans, a place from which she was removed and to which she returned. “People who were evicted would say they became impassioned. Because a person was born and raised in a place like this and then sent to hell,” continues Manoel Lambreta, the elder of the Tauá community. Sandra and Manoel have both held out on their reclaimed land because they survived the harrowing passio of dispossession in the name of progress.

The Unsustainable series is a partnership between King’s College London’s Transnational Law Institute and SUMAÚMA – Journalism from the Center of the World