Vale usurps 24,000 hectares of public lands in the Amazon

With the agrarian reform agency’s failure to act, a Brazilian multinational, that irregularly bought federal lands a few years ago, is now pressuring landless rural workers and striving to demobilize social movements in southeast Pará. Reporting done in partnership between King’s College London and SUMAÚMA

By Sílvia Lisboa (text)* and João Laet (photos), Canaã dos Carajás, Pará – May 2, 2024

“You know that this will all be destroyed?” says 62-year-old landless rural worker Valdecir Moreira Leite**, looking out at the forest-covered hills of the southeast portion of the Carajás Mountains, in Pará. The imposing forest rises over Valdecir’s orchard, where fruit trees form a cover so thick it keeps the sunlight from entering and plants from growing on the ground, leaving the moist red soil exposed. Water flows from the summit to a 500-liter water tank that overflows with the abundant discharge. The noise jumbles the senses: it sounds like it is raining, even on a sunny day. The clear icy water supplies the home where Valdecir and his wife live and it runs through hoses attached to the ground that irrigate the orchard, packed with banana, mango, and moriche palm trees. “It’s all going to turn into an immense hole, and the mountains, a pile of tailings,” says the resigned voice of the former accordian player and Paraná native who came to Pará 1980, his wavy gray hair covered by a cowboy hat. This was the first of many times that Valdecir, a member of the Rural Landless Workers Movement, would repeat the same phrase while visiting his grain and vegetable crops, which blend into the forest.

Valdecir and Inêz de Sousa, his companion of 51 years, live with over 131 families who are under threat of being expelled from public lands that Vale – a Brazilian multinational and the world’s largest producer of iron ore – claims to have purchased from 2008 to 2011 to implement its Cristalino Project for mining copper and gold. Documents are currently being assessed to issue an environmental license, according to Pará’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary. If approved, the surface mine will deforest nearly a thousand hectares of conserved forest, according to a technical note from Pará’s Public Prosecutor’s Office, based on a study and on the mining company’s own environmental impact report. Half a million trees will be culled. At least three caves, whose archeological riches have yet to be studied, will be destroyed to make way for a cavity from which 16 million metric tons of copper will be drawn – with twice as much in tailings waste. Sediments that Valdecir predicts will take the place of the hills, whose streams of clear water irrigate the orchards and crops of over a hundred landless rural workers.

Since 2015, groups of landless rural workers who had been resettled through agrarian reform in Canaã dos Carajás have been waging an unequal battle in the courts against one of the world’s largest mining companies for the right to land. They have occupied these areas in response to Vale’s growth in mines and territory over the last two decades that is encroaching on public lands in the Carajás Mountains. An advancement seen as illegal in some cases, since the mining company’s main strategy was to purchase agrarian reform resettlements, something the law does not allow – a resettlement area is classified as a land user and its lots may not be sold to third parties for a ten-year period after definitive possession has been gained, which may take decades.

An exclusive analysis by SUMAÚMA of the Environmental Registry of Rural Properties, a public database where all rural properties must register, shows evidence of Vale’s greed. Using seven corporate taxpayer identification numbers active in Pará, the mining company registered 182 rural properties covering 62,000 hectares in total, an area nearly equal to the urban area of the city of Rio de Janeiro. Of the 182 properties the company claims it owns – registrations in the Environmental Registry of Rural Properties are self-declared – 46 overlap other properties and ten are in resettlement areas, conservation units, or Indigenous Territories, in violation of the law.

The property overlapping public areas totals 17,000 hectares. Pará’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary, which is responsible for the system, has said it is investigating this case. The ten registrations overlapping resettlements and other public areas are listed in the system: six are classified as pending; two suspended; one canceled; and one active. If the information provided is found to be false, misleading or missing, the Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary says the registrations will be canceled. Environmental Registry of Rural Properties data was obtained in December 2023.

According to a survey done by the Pastoral Land Commission based on data from Brazil’s agrarian reform agency, Incra, and on court proceedings, Vale supposedly purchased 58,800 hectares of land in the Carajás region from 2000 to 2011. At least 41% (24,000 hectares) are federal public lands and agrarian reform resettlement lands belonging to Incra. These include lots currently occupied and claimed by Valdecir and another 131 families in the area where Vale wants to mine copper and by 447 families in Planalto Serra Dourada, where the company intends to mine nickel. The three areas currently occupied by farm workers, covering a total of 6,395 hectares, belonged to what were resettlements.

In 2008, the land and agrarian reform agency received reports from resettled rural workers in Ourilândia do Norte, also in the Carajás Mountains region, that the company was pressuring them to sell their lots. At the time, Vale recognized of its own volition that the purchase was irregular and it signed an agreement with Incra. Other lands were purchased and given to the federal government to resettle the families. Yet the unbridled thirst for public lands has not stopped since this report. In a report from the El País newspaper, whose reporting covered the start of the landless resistance in Canaã, resettled rural workers who sold their lands to the mining company prior to 2016 were interviewed. They said the company was asking whether the rural workers held the titles to their land, but “if they didn’t have them, they would buy it too.”

Vale makes billions from its three large-scale projects in Canaã dos Carajás: Sossego (copper), Onça Puma (nickel), and S11D, the world’s largest open-pit iron mine. In 2022, six years after the S11D began operating, it took in earnings of R$ 95.9 billion (U$ 18.6 billion), the third best result ever on the Brazilian stock exchange, trailing only gains posted by Petrobras and Vale itself the year prior. In the last year, profits fell by 53.6%, coming in at R$ 39.9 billion (U$ 7.7 billion) “based on lower average realized prices and the impact of foreign exchange losses,” according to the company

While raking in billions in earnings, Vale has continued actions to evict the rural workers from Canaã who make their living off of small crop areas that blend into the forest, most living in wooden houses. Over eight years, through struggle and hard work, they set up organized and productive camps that now supply fruit, grains, vegetables, and dairy to the residents of Canaã dos Carajás. They fought for electricity, they built schools, a workshop, a warehouse, and a community center for collective meetings – management is shared by four or five leaders in each camp. In the Planalto Serra Dourada camp, tarp tents gave way to a small community of brick-and-mortar structures – most of the landless rural workers already have brick homes and storehouses, as if they had lived there for some time. “We were only in tarps for a couple months. We built everything together,” says a proud Carlenes Pereira Silva, 53, Serra Dourada’s female leader.

After the families’ occupation, Vale filed over 60 requests to recover possession and eject them from these areas. Yet, when it filed the suits, the company did not submit to the court the definitive titles to the areas it claims to own. In the case of the Boa Esperança and Vale do Carajás farms, where it plans to install the Cristalino Project and remove Valdecir and his colleagues from their homes, Vale submitted a deed and a sales agreement binder for the areas, respectively, instead of the definitive titles. In the case of Planalto Serra Dourada, where another 447 families live, Vale supposedly “donated” the land, which belonged to the federal government, to the municipal government of Canaã, but even so it has maintained lawsuits asking for expulsion of the landless rural workers. The lack of titles to these areas is a sign that the mining giant may have purchased public farms irregularly and without the consent of Incra, the agrarian reform agency.

“Even without submitting titles to the lands, as required by Brazilian law, the trial court in Canaã issued injunctions in Vale’s favor,” says José Batista Gonçalves Afonso, an attorney for the Pastoral Land Commission, who is working to defend the rural workers. “I reported this illegal appropriation of lands to Incra [the agrarian reform agency] and to the Public Prosecutor’s Office in 2009, but so far, neither the agrarian reform agency, which could resolve the issue of regularizing the lots or demand compensation from Vale, nor the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office have taken effective measures to protect rural workers.” SUMAÚMA contacted the Judicial District of Canaã and Curionópolis, but the justices who granted Vale the injunctions are no longer assigned to these courts. After contacting the judicial districts where they are assigned, the press agent for the Pará Court of Appeals said that the justices only statements are provided in court records.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has opened an inquiry into the case and has unsuccessfully been asking Incra, the agrarian reform agency, to provide a position since 2020. In July 2022, a second request was made for Incra to carry out a survey of disputed lands, which would establish which lands Vale could have purchased irregularly. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office set a deadline of four months for a response. Twenty-two months and one presidential administration later, neither the federal government nor the agency responsible for agrarian reform resettlements have replied. “We want to meet with Incra, but we’re looking at taking the agency to court to demand this inspection be done,” prosecutor Rafael Martins da Silva told SUMAÚMA. “We are also looking at doing this survey on our own.”

Incra’s Office of the Regional Superintendent in southeastern Pará confirmed to reporters that Vale is arguing in court over federal resettlement lands. “The size of the land structure involved in mining at Vale S/A ends up affecting federal areas in various types of domain, especially in resettlement project areas,” the institute stated through Brazil’s Access to Information Act. The agency claimed it is not currently equipped to perform a survey of the land status of each disputed lot. However, it said that it would begin a diagnosis of the situation in March, through an agreement with the municipal government of Canaã dos Carajás. The agrarian reform agency had yet to provide a response as to whether or not the survey had begun by the time this story was published.

SUMAÚMA asked Vale about the problems found in the surveys done by the Pastoral Land Commission and in the Environmental Registry of Rural Properties database. The company had no response concerning the irregular purchase of lands or the rural properties it claims to own that are overlapping public lands. It only stated that “the processes of negotiation, land acquisitions, recovery of possession, and/or institution of a mining easement by the company are carried out in accordance with the law and are aimed at a fair solution and respect for established rights.” The mining company also said that it “maintains a permanent relationship with [agrarian reform agency] Incra, to stay on the same footing about land management matters, while also maintaining constant dialog with social movements and communities near its operations and projects.”

Vale also said that it “believes in family farming as a potential vocation in the state” and “has acted to drive this and other economic activities, to go beyond mining.”

Its land offensive has, however, swallowed family farming in Carajás. In a thesis paper discussing the mining company’s operations in the region, Bruno Malheiro, a professor at the Federal University of South and Southeast Pará, shows that crops of rice, beans, pineapples, coconuts, black pepper, cocoa, coffee, and passion fruit practically disappeared from Canaã from 2000 to 2015.

Mining designs an economic and political geography that goes beyond the areas mined, says Malheiro. When it opens a mine, Vale immobilizes large areas, which will be turned into roadways, railroad extensions, or export zones. In the book Quatro Décadas do Projeto Grande Carajás [Four Decades of the Grande Carajás Project] (2021), Malheiro and Fernando Michelotti provide a map of the region where Vale’s properties, its title deeds, areas of interest, and mining easements overlap a variety of resettlement areas.

“The mining dynamic employed by this company today in the Carajás region can be seen as a type of continued war, no longer between powers, but a war on the material conditions of the lives of a variety of peoples, groups, and communities affected by mining and all of its social metabolism,” the researchers write.

The promised land

Landless rural workers began to occupy the Carajás region in the 1980s, encouraged by the business-military dictatorship (1964-1985) as part of the supposedly nationalist ideology of the Brazilian military to “integrate so as not to surrender” the Amazon to foreigners.

At the time, Vale was already mining the region, which had gained international notoriety for what was then the largest illegal mine in Latin America: the Serra Pelada. Mined by thousands of illegal miners, Serra Pelada became known for its frightening images of a human anthill. It was at this same time that the mining company began to tear the forest apart with the expansion of the Carajás Railroad. At 972 kilometers, today the railway crosses through 27 municipalities, 28 conservation units, and 100 communities where rural workers, Quilombolas (the descendents of enslaved rebels), and Indigenous people live, to distribute tons of ore from southeastern Pará to the Ponta da Madeira terminal, next to the Port of Itaqui, in Maranhão – and from there mostly to China.

From agrarian reform to the world's largest open-pit mine

Vale's growing mining operations in the Carajás region are encroaching on resettled areas in Pará and ringing in a new chapter of land conflict

1982

Still operating under the business-military dictatorship, Brazil's agrarian reform agency, Incra, creates three large resettlement projects in the region, the Carajás I, II and III Resettlement Projects, to encourage the migration spurred by the mining industry. They surround mining areas belonging to what was then Companhia Vale do Rio Doce

1983

Mining activities at Serra Pelada, carried out by independent artisanal miners, reach their peak and gain international notoriety in images of a ‘human anthill’ (the mine closed in 1992)

1990

Plans for agrarian reform grow as democracy opens the country. Yet in the end, most of the resettlement areas are not given regular legal status, causing uncertainty and land conflicts

1996

The region becomes the setting of the Eldorado dos Carajás Massacre (124 km from Canaã dos Carajás), where 19 landless rural workers were murdered by the Military Police, with international repercussions

1997

Companhia Vale do Rio Doce goes private

2003

Taking advantage of an omissive agrarian reform agency, Vale begins to purchase settled rural workers' lands to expand its mining projects. It had purchased lots inside the Tucumã and Campos Altos Settlement Projects, in Ourilândia do Norte, and in the Carajás II and III Resettlement Projects, in Canaã dos Carajás and Curionópolis, a transaction that, by law, can only take place after 10 years of definitive ownership

2009

The Pastoral Land Commission reports Vale for irregular land purchases from the federal government (24,000 hectares). The Federal Public Prosecutor's Office opens an inquiry to investigate the mining company's appropriation of public lands, which is still ongoing

2012

Vale obtains a preliminary license to explore the S11D mine, considered the largest mining project ever at the time

2015

Noticing that resettlement areas are slowly being dissolved, four groups of landless rural workers occupy the public areas Vale is claiming to possess in Canaã dos Carajás and Curionópolis. A legal dispute begins that continues to this day

2016

The S11D mine is opened, kicking off a new era of soaring profits for Vale

2017

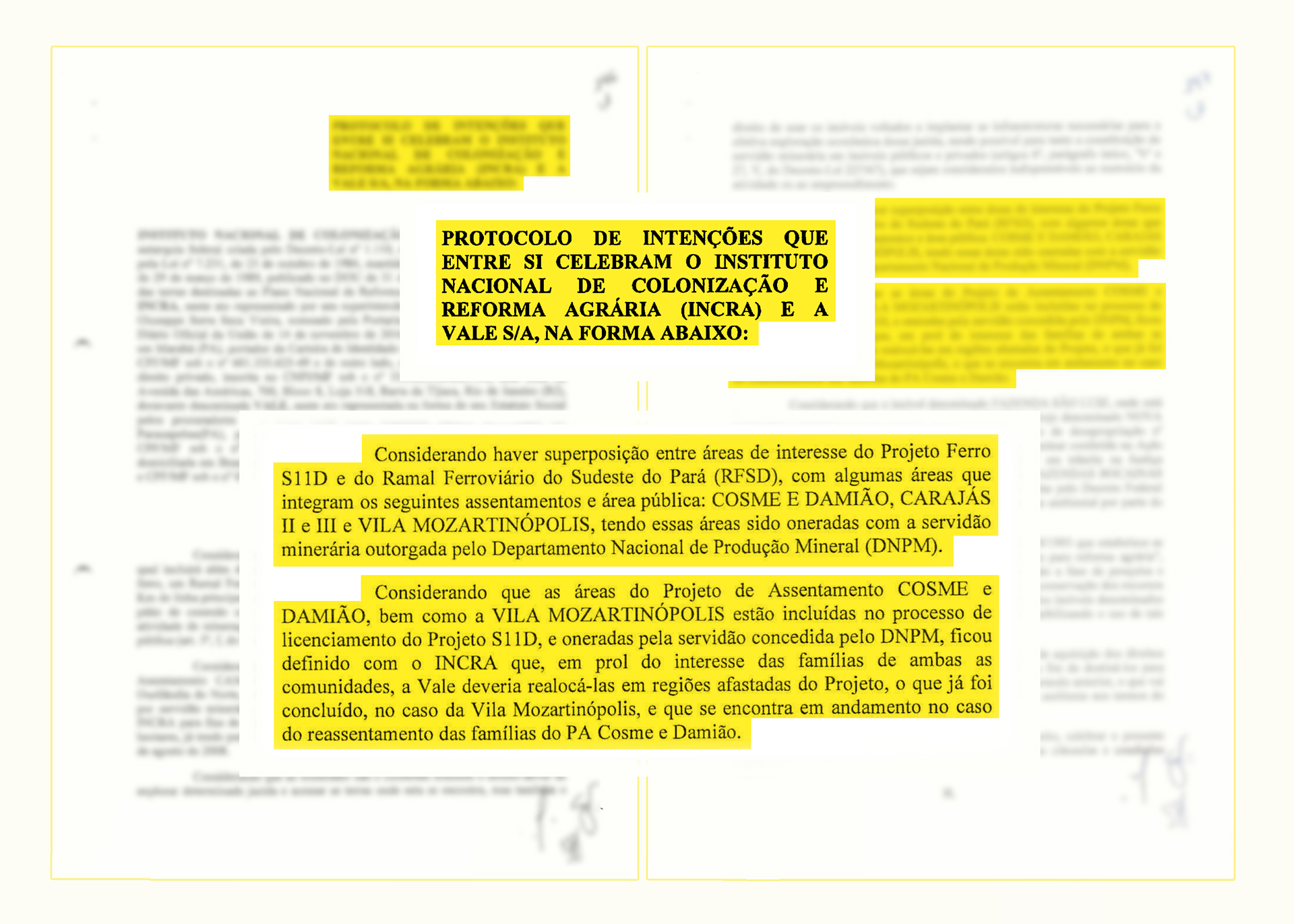

Vale recognizes that resettled lands were purchased irregularly and starts negotiations with Incra to purchase new lots and resettle the families, with the participation of the Pastoral Land Commission

2019

The Bolsonaro administration staffs Incra and halts agrarian reform. Vale stops negotiating land purchases with the agency and changes tack: it starts to demobilize the region's social movements and continues to threaten rural workers with actions to recover possession of properties

2020

The Federal Public Prosecutor's Office asks the agrarian reform agency, Incra, to survey the lots and lands in dispute – this request goes unfulfilled by the land management agency

2022

The Federal Public Prosecutor's Office sets a four-month deadline for Incra to perform the survey – to no avail

2024

In January, Incra told SUMAÚMA that “the size of the land structure involved in Vale's mining operation ends up affecting federal areas in various types of domains, especially in resettlement project areas,” and it says that it will start a detailed survey of the lands in dispute in March of this year

Swipe right

Swipe right

Sources: Pastoral Land Commission surveys and documents sent to the Agrarian Development Ministry's (Incra) ombudsman; court proceedings against rural workers from the Cristalino region and from Serra Dourada; ‘O que Vale em Carajás? Geografias de exceção e r-existências pelos caminhos do ferro na Amazônia’ – a doctoral thesis by Bruno Malheiro (Universidade Federal Fluminense); recommendation sent by the Federal Public Prosecutor's Office to Incra; Incra's response, obtained through the Access to Information Act; Federal Public Prosecutor's Office Inquiry no. 1.23.001.000318209-77; ‘A ação do Getat na região sul e sudeste do Pará,’ a thesis paper by Wilson Corrêa (Universidade Federal do Sul e do Sudeste do Pará)

Eyeing the potential billions to be made from its state-owned enterprise, the dictatorship outlined an occupation plan to favor what was then Companhia Vale do Rio Doce (the mining company’s name prior to 2009). It decided to create settlements to replace people holding lands illegally and large landholders who had arrived there earlier, encouraged by the same dictatorship that now wanted to drive them away. In the military’s eyes, the settlements would ensure greater State control over lands, which would remain under federal possession.

The military dictatorship’s ideology for the Amazon, which was responsible for the abuse and massacre of Indigenous people, massive deforestation, the contamination of rivers and agrarian conflicts that are unresolved to this day, then turned to the creation of three enormous resettlement projects in the 1980s: the Carajás I, II, and III Resettlement Projects. They covered 75,000 hectares, an area larger than the urban area of the country’s second largest city, Rio de Janeiro. They were so large that they had administrative centers, known as regional development centers. The region became known as the “promised land” for the landless, and in 1982 the development centers gave way to the municipality of Canaã dos Carajás, whose name alludes to the biblical region of Canaan.

To resolve the problems specific to Pará’s south and southeast, which was at this time was already a violent region because of land disputes, in 1980 the dictatorship also created an arm of its agrarian reform agency, Incra, that could exercise police authority: the Araguaia-Tocantins Lands Executive Group. Connected to the office of the National Security Council Secretary, the agency worked with land regularization to alleviate conflicts and protect mining activities, acquiring illegally-held lands, which were passed to the federal government for agrarian reform purposes.

The resettlements saw resistance from large landholders and many farmers were threatened or expelled. Starting in 1985, with the country’s redemocratization, Incra began to take on the power of large rural property owners, who had now organized around the Ruralist Democratic Union, a sort of militia created in response to the emergence of the Rural Landless Workers Movement. The resettlement projects in the Carajás region, along with many others, fell into an administrative and legal limbo because of how long they took to implement, while at the same time continuing to attract new farmers. The largest was never totally regularized, which continued to fuel tensions. In 1996, the Carajás region saw one of the largest massacres in recent decades: 19 landless farmers were brutally murdered by the Military Police in an episode known as the Eldorado dos Carajás Massacre, which gained international notoreity. The crime was committed at the S-curve of the PA-150 highway, 124 kilometers from Canaã.

In 2012, Vale obtained a preliminary license to explore the S11D mine, part of which is located inside of Carajás National Forest, created in 1998, the year after the company was privatized. At the time, the mine was considered the company’s largest project to date, as well as the largest private investment in Brazil during that decade. Opened in 2016, it kicked off a new era of dizzying profits for the mining concern.

Ever since, Canaã dos Carajás has been experiencing a demographic explosion: it is the fastest growing municipality and has Brazil’s second highest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita: R$ 894,806.28 (U$ 173,400) – more than 20 times the average in Brazil of R$ 42,247.52 (U$ 8,200). The population shot up from 26,700 in 2010 to 77,000 in 2022, an increase of 189%, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Most of the money raised from mining royalties (Financial Compensation for Mineral Exploration) is used to defray the costs of government machinery and pave the roads accessing the mines. Taxes from mining activity accounted for 66.3% of the city’s total revenue in 2019, according to a study by the Institute for Socioeconomic Studies, with little social investment: only 0.32% went to environmental management, 0.44% to culture, 1.8% to social assistance, and 4.61% to basic sanitation. The study concludes that the city is not looking to overcome its dependence on mining activity – and the S11D mine may be exhausted by 2060.

Although it lies in the middle of a forest area, Canaã is an arid city with few trees. The municipality grew outward from a large avenue and it now has a bike path, dozens of stores selling clothes, mobile phones and furniture, supermarkets, and gas stations. White trucks and people wearing the uniforms of the third-party companies that provide services to Vale pass along its paved streets. Residents praise the hospitals and everything seems organized to the standard of a mid-sized city in the middle of the Amazon. The urban sterility is, however, at odds with the imposing forest surrounding it and with the cultural riches of the rural camps. That is where the contrasts are: while a high percentage of Canaã has basic sanitation, the rural zones visited by SUMAÚMA have septic tanks.

‘Cash cow’

Vale, control of which is now spread across the market, has an appetite that is the result of an aggressive policy of growth and cost-cutting. Researchers point to this impetus as being behind the Mariana disaster in 2015 (in a consortium with Anglo-Australian group BHP) and the Brumadinho disaster in 2019. A total of 289 people died in the two environmental disasters and a sea of toxic sludge contaminated the rivers and ground in Minas Gerais, swelling beyond the state’s borders, in two of the biggest ecological crimes in Brazil’s history.

“Today, Vale is considered a ‘cash cow,’ that is, a company geared toward generating dividends for shareholders,” says Thiago Aguiar, a doctor of Sociology, a researcher at King’s College London, and the author of the book “O Solo Movediço da Mineração” [Quicksand of Mining] (Boitempo, 2022). Previ, Banco do Brasil’s employee pension fund, is its biggest shareholder, along with Japanese mining company Mitsui and the BlackRock investment fund. Nevertheless, these three only hold 21% of the company. The rest is held by countless stock market investors. Bolsonaro reduced the federal government’s controlling share in Vale, but the company benefited from hefty tax breaks that totaled R$ 19.2 billion (U$ 3.7 billion) in 2021 alone, according to calculations by Fiquem Sabendo, an organization specialized in accessing public information. “We don’t even know who owns Vale” is said repeatedly by the farmers of Canaã, who are accustomed to the company’s veiled actions. In Carajás, mining is hidden behind the mountain ranges – the only part visible is the intense movement of trucks and machinery along recently paved roads.

All of this hunger for profits has impacted Carajás. Vale expanded its geographic domain by irregularly purchasing four areas to implement two projects: Red Nickel (now abandoned) and Cristalino, a copper and gold mine. Along with the expansion of the Sossego mine, operational since 2004, the Cristalino mine is part of a strategy to boost the production of basic metals in the Canaã dos Carajás region to supply the industry with raw materials for the energy transition, such as producing electric car batteries. If approved, Vale will excavate the still-conserved southeast portion of the Carajás Mountains over 24 years. Those buying CO2 emissions-free vehicles may, ironically, believe they are investing in environmental conservation without knowing about the land, environmental, and human rights problems behind the production of these batteries.

The lands Vale purchased irregularly would, according to the company, give it ownership over the Vale dos Carajás, Boa Esperança, Serra Dourada, and São Luiz farms, which sit over the old resettlement areas or on public property belonging to the federal government – the Carajás II and III Resettlement Projects and the Buriti Parcel. These are the areas the Pastoral Land Commission considers to be the fruit of illegal appropriation of public lands and that were occupied by landless workers and people who were formerly resettled, in a unique movement of resistance in Pará’s southeast.

The company immediately reacted to the farmers’ occupation and filed dozens of court requests to recover possession. The courts authorized one of them in 2015, which was carried out by police and resulted in violence. The crops of 150 families – who occupied lots on the São Luís Farm within the Carajás II Resettlement Project – were destroyed using tractors on loan from Vale, according to the farmers evicted. “I remember women fainting while watching crops of ripe tomatoes and corn being crushed,” recalls one of the leaders, small-hold farmer Edson Ramos. According to findings by the agrarian reform agency Incra, the São Luís Farm is comprised of lots that were regularized by the old Araguaia-Tocantins Lands Executive Group and of resettled lands in the Carajás II Resettlement Project, federal government property.

The removals were suspended when the Pastoral Land Commission’s attorney began defending the farmers. Batista, as he is better known, helped to create 481 resettlement areas in the Amazon in Pará’s south and southeast. Thanks to the Pastoral Land Commission’s fight in alliance with social movements, over 80,000 families guaranteed their constitutional right to the land in the courts.

To prevent the farmers from being ejected, their lawyer called up the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará to provide notice that Vale was treating the occupations as individual conflicts. However, this case was obviously an agrarian conflict, which should be heard in the Agrarian Court of Marabá. The Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará joined the suit, asking that proceedings be transferred.

It is well-known in the legal area that outside of the agrarian courts, which were created to resolve collective disputes over land possession and ownership, family farmers do not have a chance. The courts granted the Pará Public Prosecutor’s request and the case began to move through the Agrarian Court of Marabá, 163 kilometers from Canaã. The family farmers gained time.

By filing suits to recover possession, Vale gave the farmers new ammunition. The company submitted expired documents to prove ownership of the lands. To prove possession or ownership, Brazil’s Civil Code stipulates that a land title must be registered and, later, a title deed, confirming that the property changed hands.

In one of the requests to recover possession of the Cristalino Project areas, for example, Vale submitted a sales agreement binder to the courts for the Vale dos Carajás Farm. Because the very nature of the document makes this clear, these documents are just promises that, despite being registered with a notary, do not prove ownership. There is even another problem in the contract submitted by Vale. The sales agreement binder attached by the mining company stipulates a one-month term for deed approvals to be finalized. Because they date back to 2011 and were delivered to the court as proof of ownership in 2015, there is a hiatus of at least four years from the date stipulated to approve the deed – which has still not occurred – and submit it to the court as proof of ownership. When asked by SUMAÚMA about the lack of a title and deed on one of the Cristalino areas, for which documents are being considered for licensing, the mining company responded that the area is “duly registered,” yet the document requested was not provided.

Vale only submitted a deed for one of the areas, located in Curionópolis and called the Boa Esperança Farm, yet the land title was not attached. An investigation by the Pastoral Land Commission based on documents from the agrarian reform agency Incra show that its perimeter lies within the Buriti Parcel, which is federal government property. In other words, according to the investigation, Vale had purchased misappropriated public lands. “We asked Incra for the title to this land, but Incra never responded. It’s in Vale’s interest to prove that it owns the land, which is why it should have attached the title to the process, but it didn’t do this,” Batista explains. (In 2009, a commission to fight misappropriation of public lands asked notary publics for all of the deeds for land registered in Pará. It found that the area “registered on paper” was four times larger than the area of the state, providing evidence of landgrabbing and the chaotic land management that favors conflicts.)

Yet Vale continues to fight for ownership of these areas using legal means, and the threat of an adverse ruling is constantly hanging over the resettlement areas. “It’s up to Incra to resolve this conflict,” says Batista, a thin man who bows his head and looks over the frames of his glasses when he addresses someone.

The attorney is currently defending 575 families’ rights to the land in Canaã dos Carajás and Curionópolis. Fifty-seven families occupy the Vale dos Carajás Farm and another 71 live on the Boa Esperança Farm, where Vale intends to implement the Cristalino Project. The Serra Dourada Farm, located in a highland region 11 kilometers away, has the biggest camp, with 447 families. There, the company intends to mine nickel, but it has transferred the mining rights to Horizonte Minerals, a mining company headquartered in London.

In an unusual move, during the legal dispute with the farmers of Serra Dourada, in 2018 Vale “donated” the 1,600-hectare area to the municipal government of Canaã, to “contribute to development of the municipality,” it said in the transfer document. Except this area belongs to the federal government. “The company feels so at ease occupying federal public lands that it uses these properties to negotiate with public and private entities. Taking advantage of the complete ineffectiveness of [the agrarian reform agency] Incra, Vale promoted the donation of these areas to the municipal government of Canaã, as if it owned these properties,” Batista informed the Agrarian Development Ministry in December of last year. Even without any interest in exploration and without ownership of the land, the mining company continues to press requests to recover possession, asking for the ejectment of the families, a community of 1,500 people, including children and the elderly, who built their homes on their own, with electricity, running water, and crop-growing areas that supply the city of Canaã.

In the latest hearing on the case, the company suggested negotiation, which was refused by the small-hold farmers’ attorney. “Vale no longer has the land, it no longer has the mineral rights to mine the land and it wants to negotiate. Negotiate what?” Batista asks. “We are waiting for the courts to finalize this process, and the farmers are staying in the area.” Vale confirmed to SUMAÚMA that it had transferred the mineral rights, but gave no explanation of why it continues trying to evict the farmers in court.

With the small-hold farmers successfully holding back Vale’s legal department, the mining company shifted its strategy starting in 2017. The legal dispute was no longer a priority and instead it began to negotiate with Incra and the Pastoral Land Commission to purchase lands for resettlement in new areas, a sign that it will advance irregularly over public areas. It offered five pieces of land in municipalities near Canaã. The families did not accept the offer, as the land was far away and had no deed, a result of the land management chaos in the Amazon.

In late 2018, an election victory by extreme-right presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro (then with the Social Liberal Party) put an end to direct negotiations between Vale and Incra. Bolsonaro suspended agrarian reform, staffed the agrarian reform agency with cronies and appointed a general to run it. He also named Luiz Antônio Nabhan Garcia, a member of the ruralist bloc and formerly the president of the Ruralist Democratic Union, as special secretary of Land Management Affairs at the Agriculture Ministry.

With Incra paralyzed and negotiations stalled, the mining company began a movement to sabotage the mobilization by the farmers.

Harassment in the forest

On April 12, 2023, Valdecir Moreira Leite received a breathless call from one of his camp colleagues, Adailton. Two Vale employees were having lunch at the home of one of the leaders. Adailton had arrived at the home of farmer Maria Clara Vieira Silva by chance and had encountered the scene.

The two employees began to visit the camp after Incra withdrew from negotiations. They said they wanted to get to know the families, the crops produced, and take a census of who lived on each lot. The farmers welcomed them with cups of super-sweet coffee, a local tradition, but they kept some distance. It was also customary to notify the other leaders each time Vale called or visited.

Maria Clara had not notified her colleagues about this lunch. The evening before, at one of the collective meetings, Valdecir had noticed she was more reserved. She had not agreed to their proposal to close the road to stop Vale’s exploratory incursions, as a way to pressure the mining company. Why would the behavior of such a combative leader change?

Right after he hung up with his colleague, Maria Clara called Valdecir. “She told me she ‘urgently needed to gather the people.’ I asked what it was about, that this wasn’t how things should be done, that she couldn’t make any decisions by herself,” he says. It was then that Valdecir noticed that the leader had “signed” with Vale – a term the farmers use to identify who was convinced by the company to receive indemnification to leave their lands. He said he felt ill and had to seek care at the hospital in Canaã dos Carajás for a hypertensive crisis. When he came back to the camp, Maria Clara had resigned from her leadership position.

The farmer signed a deal with Vale to sell her 22 hectares – after occupying the land in 2015, the small-holder farmers split it into equal lots. Over the next seven months, another 71 families also sold their lots. According to those in the camp, the mining company paid 80% up front and conditioned the final payment on the removal of the shack and wooden sheds. They were ordered not to leave anything behind. The remains of shack boards could still be seen in January, in clearings near the highway, and crop areas were being overtaken by forest.

Nobody knows how much Vale paid each family. The farmers estimate somewhere around R$ 350,000 (U$ 67,800). Maria Clara told SUMAÚMA that she received less, but did not specify how much – Vale also did not wish to share the amount with reporters. “The company calls them one by one, says that it’s a confidential agreement and writes an amount on a little piece of paper. If a settler [a landless farmer] agrees, they sign a contract and aren’t given a copy when they leave,” Valdecir says. “They don’t even know when they’ll get paid. They [the Vale employees] are psychologists. They get into people’s heads. They know how to persuade, make people afraid, confuse them.” What Valdecir said was backed by other members of the camp and by Batista.

Maria Clara told SUMAÚMA that she did not convince anyone to take the indemnification from Vale. “Even before I decided, I left my leadership post. If anyone followed me, it’s because of influence as a leader, but I don’t see this as convincing on my part,” she says. “I decided to go with an individual negotiation because I’d already been in that area for eight years.” The camp’s former leader also said she was paid the amount agreed upon with the mining company. “With the money, I could buy a piece of land, and Vale always said they weren’t going to give [us] any land. So, since I was there eight years, and the binder for the land didn’t have an expiration date, I decided to take it. Thank God I’m on land that I can say is mine, planting, harvesting, and surviving off of it.”

The smallholders say part of the company’s strategy is to pay the leader more, tasking them with the mission of swaying their companions or inspiring others to do the same. After Vale convinced the pastor in what was formerly Mozartinópolis, a community destroyed to make way for the S11D mine and an extension of the Carajás Railway between 2008 and 2014, half of his faithful left with him. “The believers went with,” recalls farmer Marcos Vinício Santos, a former resident of Mozartinópolis, who has since been resettled in the União Américo Santana Resettlement Project, also in Canaã, after a negotiation with Vale that lasted four years.

In the Cristalino region, 132 families are fighting to stay on the land or be resettled in a nearby area. They put up with harassment from the security guards who travel along the dirt roads snaking through the mountains – they call frequently, urging residents to sell. “This here is public land, resettlement land. We have the right to be here. But, in our world, mining royalties are worth more than food and the forest,” laments Manoel Alves, one of the leaders. “This is the ‘problem’ here: it’s lots of wealth together.”

In the Serra Dourada occupation, the farmers said that third-party security guards entered the lots with documents in hand they claimed were “injunctions” issued by the courts. This move caused a general panic, and leaders had to meet frequently to keep things calm.

The Serra Dourada group responded to these intimidations by joining together five times to block the Carajás Railway and the entrance to the S11D mine. “One time, we arrived at the protest and there was already a court official with an injunction to prevent us from shutting down the railway. Vale spies on us,” said farmer Eduardo Nascimento, one of the leaders, and also the victim of a criminal complaint. “We wanted to talk to someone with the power to make decisions, but the company refused. At the last protest, we were able to catch the attention of the agrarian ombudsman.” Over nearly nine years of occupation, the camp has become a reference in agricultural production in Canaã.

The milk produced by Eduardo Silva do Nascimento, who lives in the Planalto Serra Dourada resettlement area, supplies the city of Canaã dos Carajás

Gleide Carvalho and her daughter Tamires say that the structural cracks in their house in Vila Bom Jesus were caused by explosions at the Sossego mine

Rural life resists in Canaã dos Carajás, a city dominated by Vale’s mining operation

The Landless Workers’ Movement’s Terra e Liberdade Camp, with its 5,000 people, is located near the railway in Parauapebas

A railway used by the S11D mine, part of the world’s largest iron mining complex, in Canaã dos Carajás

Waterfalls and caves could be destroyed if the mining company is able to approve installation of the Cristalino Project to mine copper in the Carajás Mountains

Divide to conquer

Vale’s strategies are recurrent. Geographer Bruno Malheiro wrote a thesis analyzing the company’s relationship with the populations around its mines and he identified two areas where the company acts: social demobilization, with individual payments, and by encouraging internal contradictions to emerge in communities. Malheiro interviewed farmers, Quilombolas, and Indigenous people who live near the mines or whose territories were crossed by the railway. Their reports showed systematic methods of persuasion and harassment, like in the Canaã camps.

In a statement to Malheiro, Kátia Silene, a cacique of the Gavião Akrãtikatêjê people, talked about how Vale was able to convince Indigenous people to agree to a doubling of the railway. The action she describes matches what the small-holder farmers in southeastern Pará describe. Train tracks cut across part of the 62,000 hectares of the Mãe Maria Indigenous Territory, 250 kilometers from Canaã dos Carajás: “Vale comes here and negotiates with me, then they go to the other guy and say: ‘Well look, Kátia agreed, she says she’s going to sign over there to agree to doubling.’ Then the other guy calls me: ‘Hey, did you agree?’ Then I say: ‘It’s a lie.’ Then one person calls another and then we find out that nobody agreed.”

Vale used the same tactics to demobilize the people resettled in Ourilândia do Norte from 2003 to 2007 to build the Onça Puma nickel mine, which had its license to operate suspended by Pará’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary in February of this year. The mine had previously been closed by a court order because of pollution in the Cateté River, which supplies water for the Kayapó Xikrin people. Without consulting Incra, the company irregularly purchased agrarian reform lots, according to a document from the agency shared by Folha. At the time, the smallholders said they felt coerced to agree to the proposal. “This situation [of resettlements being dismantled] was triggered by the mining company, which, despite its awareness of the illegality of the situation and without having received formal authorization from this authority, carried out negotiations with the resettled community, with a very tempting proposal,” says one passage from the Incra report.

The tactic of demobilization was even exported. In his book “Solo Movediço da Mineração,” researcher Thiago Aguiar discusses how Sudbury, a mining town in the interior of the Canadian province of Ontario, was disrupted after Vale arrived in 2006. Vale was used to dealing with high worker turnover and weakening unions in Brazil, but there found itself trying to negotiate salaries with the powerful United Steelworkers, the largest private union in North America. There, agreements are made through collective bargaining between the company and the union. Facing an impasse in salary negotiations, Vale refused to sign the agreement and the employees went on strike. For one year.

The company did not give in to the demands and took advantage of a drop in nickel prices on the international market to cut operating costs and contract third-party workers. “Vale surveilled activists and sued leaders for the damages caused by the strike. This disrupted families. There were divorces, debt, and suicide. A lot of people left the city,” says the researcher. “The mining company also brought in third-party workers from Quebec, an affront to the union leaders.”

One of the Canadian miners who spoke to Aguiar talked about how the strikers were persecuted. “[In 2009] They followed us, filmed us, sued us. My family and I are being sued: I think I have three different lawsuits. After the strike ended and when everything was resolved, the lawsuits were finalized. But this was done to stress and put pressure on people and their families.”

Six years later, the strategy would be repeated in Carajás. Farmer Edson Ramos and nine other farmers were sued by Vale after they protested to remain on what is public land, the São Luiz Farm. In the criminal complaint filed with the court, lawyers for the mining company laid the corporate espionage bare. They attached long forms on leaders, with names, photographs, profiles, and license plates, as if it were a police investigation. “They do everything they can against us,” Edson says. Critics are charged with possessory usurpation, a legal term referring to the act of taking possession of property without due entitlement or authorization. When asked about the farmers’ report of espionage, Vale said it makes legitimate use “of the means and resources provided in Brazilian law when legal proceedings are moving through the courts.”

After retaking the area (still belonging to the federal government, according to agrarian reform agency Incra), the mining company promised those evicted that it would include them in other resettlement projects negotiated with Incra and intermediated by the Pastoral Land Commission. None of this happened. Raimundo de Sousa, 67, still keeps a plastic folder with the piece of paper Vale distributed to resettlement members in 2019. It contains the farmers’ profile and a promise that they would receive a piece of land and a two-room house. “Vale didn’t come to negotiate, it came to take land from us,” says the farmer, who lives in a wood house in the center of Vila Bom Jesus, with no crops and no orchard around it, two kilometers from the Sossego mine’s tailings dam.

Reports of espionage have been made since 2004, when a head of security at what was then Companhia Vale do Rio Doce confessed to the Federal Police that he had a database on Gavião Indigenous people and on prosecutors in Marabá. In 2013, one of the company’s former employees testified before the Federal Senate about how Vale inspected the communities near projects by using wires, tapping phones, infiltrating communities, and producing dossiers. Even when it loses its lawsuits against leaders, Vale usually appeals to the court of last resort.

‘We lack for nothing’

Less than one kilometer from Valdecir’s shack in the southeast part of the Carajás Mountains lives Silvanete Alves de Souza, 51, and her husband Divaldo de Jesus Nascimento, 39. They live on the highest lot in the Buriti Parcel, one of the public areas coveted by Vale for copper mining.

Silvanete and Divaldo grow rice, beans, corn, bitter cassava, pineapple, and a wide variety of fruits and vegetables. Except for the evident rows of corn, the other crops mix together with the trees in the forest and are irrigated by the water that pours down from the mountains and flows through hoses attached to the ground. “We lack for nothing,” says the 51-year-old Maranhão native, who is also a teacher at the camp. Her husband adds: “When we climb the mountain, we start to breathe better. There’s something there that makes you want to stay forever,” he says.

Silvanete and Divaldo also came to the area in 2015, hailing from another resettlement project, and they dream of staying there. Gustavo, their nephew, spent some time with his aunt and never went back home. And four years went by.

In their forays into the forest, Divaldo and Gustavo usually bring back orchids for Silvanete, which she ties with wire to the trees in the orchard. It is not rare for them to return ecstatic with the discovery of a cave.

The Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará is recommending caution in analyzing the environmental licensing documents for the Cristalino project, a job given to Pará’s Office of the Environment Secretary. “We’re therefore dealing with property that is unique in the nation, whose size and importance have yet to be investigated, whether due to matters of time, scientific methodology, financial resources, political interest, or any other causes (…) There is no question that in this case the ‘Precautionary Principle’ applies,” recommends a technical note from the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará.

The region’s archeological wealth sprouts from the land like trees. While cutting back weeds, farmers have found artifacts that they believe to be traces of the Amazon’s ancestral peoples. Gustavo carries with him a polished gray stone with black tips in the shape of a three-leaf clover that he found near the where the corn grows.

If it moves forward, the Cristalino project will put not just caves, archeological objects, and the countless more-than-human lives at risk in the region, but also the forest itself. Valdecir, the farmer, can not wrap his head around it: “I don’t know why the government asks for foreign money to conserve the Amazon if the government is the one authorizing its destruction.”

*Data contributor: Reinaldo Chaves **Correction: This report was updated on May 2nd, at 2:00 PM Brasilia time. The first and last name of farmer Valdecir Moreira Leite were corrected

Fear of another Brumadinho, this time in Pará

Two kilometers from the Sossego mine, a copper mine in the Carajás Mountain Range, trembling floors and cracked glasses are part of everyday life for the 1,200 residents in Vila Bom Jesus

Por Sílvia Lisboa (texto) y João Laet (fotos), Canaã dos Carajás/Pará

On Mondays, around two in the afternoon, the sound of a stampede echoes through the air. The ground shakes, cups crack, pots fall from the shelf. A gray cloud rises from the earth and covers the crops, the animals, and the nearly 300 homes in Vila Bom Jesus, one of five rural communities in Canaã dos Carajás, located 21 kilometers from the entry to the municipality. White trucks disappear over the horizon as they move toward the Sossego mine, a copper mine run by Vale with a tailings dam that sits just two kilometers from the community, 397 meters from the resettlement’s nearest lot of land, and a mere 115 meters from the Parauapebas River.

The weekly explosions occurring over the last 20 years to open more holes to excavate Vale’s Sossego mine, in Canaã dos Carajás, have also chipped the tile floors of two rooms in a home belonging to Maria de Lourdes da Silva, 68, a native of Pernambuco who lives two kilometers from the mine. Outside, the walls are cracked, which has loosened the tiles. Vale says it is not the explosions causing the damage. The problem, the mining company says, is that the house is old. “They come here and say they have nothing to do with the explosions, that everything is broken because it’s already so old,” says Maria.

The hamlet is home to a community of rural workers who mostly came from Brazil’s northeast region in 1984. The main streets are paved. There is a school, a health post, shops, a bar, and an Evangelical church. The 2010 census showed that its 1,200 inhabitants make their living off the land, supplying a local market that operates seven days a week out of a pavilion built by the municipal government.

Despite its infrastructure and proximity, for Vale, Maria and the 1,200 residents of Vila Bom Jesus do not exist. The rural community was not included on the Environmental Impact Report submitted when the project was approved in the early 2000s. There is no mention of the community and its small farms among the 21 social and environmental impact indicators listed in the report. According to residents, the company’s relationship with the community expresses this disdain. “We weren’t supposed to be trying to get their attention. They were supposed to be concerned about us,” says José de Souza Barroso, 52, who is better known as Tio Julio. In 2021 alone, copper sales from Vale mining operations brought in R$ 14 billion (U$ 2.7 billion).

After lots of complaints from residents, Maria says some mining company employees came out to measure the decibels from the explosions and the dust that covers the crops and animals. “That day, the explosion was pretty weak,” she said. “I wonder why?” she asks sarcastically. Her daughter-in-law, 40-year-old Francileide da Silva, cuts in: “The worst, for me, is the sirens. The siren rings every month on the eighteenth as part of an accident drill. It’s so we can prepare for a break in the tailings dam,” she explains. “If it breaks, we have to run to three points in the community. I’m not sure why, maybe so we all die together.”

For five years, ever since the Brumadinho tailings dam broke in the state of Minas Gerais, killing 270 people and blanketing rivers and forests in 300 kilometers of toxic sludge, the residents of Vila Bom Jesus have been on high alert. The siren rings out every eighteenth of the month, but Francileide says it rings in her head every day. “Once it rings on a different day, then it’s for real. How do we live with this? I want to get out of here. I can’t take it anymore, my son is filling sheet after sheet [of medical records] at the [health] post because of breathing problems from the explosions, and I’ve got this anxiety,” she unloads.

The land on which Maria de Lourdes and Francileide live is near Vale’s easement area. Their homes are so close to the Sossego mine that they fall inside of a zone where Vale could, at any moment, ask to install infrastructure for mining activity. In addition to being ignored by the company, Vila Bom Jesus could be the second rural community to be engulfed by the forward march of Vale’s mining operations over resettled lands – the first was Mozartinópolis (read more below). Maria de Lourdes was unaware of this until a community meeting on January 10 where José Batista Gonçalves Afonso, an attorney with the Pastoral Land Commission, read off a list of rural workers whose properties were inside of this perimeter. “Vale always said there was no interest at all in our area. Now I find out that yes, there is. You can’t believe anything they say,” she says. “The other day, they even said the pollution from the explosions won’t reach here because of the direction of the wind. Now they control the wind?”

She is talking about the Bacaba Project, an extension of the Sossego mine to increase the amount of copper mined and that, if approved, will turn the community into a green island surrounded by gray holes. The Office of the Environment Secretary of Pará said the request to license Bacaba is still being considered. “We’re already surrounded. We can’t fish in the [Parauapebas] river anymore, because Vale’s security personnel take our boats, hooks, even the fish,” says Edson. “Even so, the fish aren’t edible anymore because of the contamination.” The residents lament no longer being able to raise chickens because the eggs fail to hatch – they go rotten inside.

Edson saw the Parauapebas, known for its fast-flowing waters, turn a phosphorescent blue color and he sent a picture to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office. A pipeline coming from the mine releases water into the Parauapebas River near a side-road entrance to the Sossego mine. One year ago, after noticing backhoes around the community, he registered a trench being built. “Vale made a trench to separate its land from the rural workers’ land. The animals fall in and die,” Edson says. The other barrier is a dike over 20 meters tall to prevent any river flooding from running into the mine. “Know where this water goes? On top of our crops.” Vale had no response when asked why it had dug a trench and about water pollution.

The inquiry by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, which is looking into Vale’s purchase of resettlement area lots, will also, along with the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará, enlist the Federal University of Pará to produce expert evidence to assess the social and environmental impacts of the Sossego mine on Vila Bom Jesus. “In 2009, I asked the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office to take measures because of the proximity to the mine. Fourteen years later, the inquiry has yet to finish,” says Batista. “The population is very vulnerable, but we have to insist.”

Vale denied that the Sossego mine had any relevant environmental impacts on Vila Bom Jesus. In a statement sent to SUMAÚMA in January, it said the company “maintains the environmental controls set forth in environmental licensing and monitors air and water quality at its operations.” The company also stated that “all of these controls and this monitoring are overseen by Pará’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary and were subject to an inspection by the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará in 2022, which concluded that Vale is operating within legally established environmental standards.”

However, one month after reporters visited Vila Bom Jesus, the Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary suspended environmental licenses for the Sossego and Onça Puma (nickel) mines. The Secretary’s office told SUMAÚMA the order was given “because of nonconformance in annual reports on environmental information and a failure to comply with actions to mitigate impacts resulting from mining activities, resulting in conflicts in communities near the operations’ area of influence.” Vale was able to resume operations at the mines after filing for injunctions in civil court in Canaã dos Carajás and in Ourilândia do Norte. On April 4, Pará’s Court of Appeals struck down the injunction that authorized operations to resume at the Onça Puma mine and, on April 15, at the Sossego mine, after considering appeals filed by the state of Pará. The two mines are not operating at the moment.

Like in the Cristalino (copper) and Planalto Serra Dourada (nickel) regions, Vale kicked off its strategy of demobilizing resistance in Vila Bom Jesus. It negotiated individually with two rural workers and went to court to ask for the lot belonging to José Barroso, aka Tio Julio. “A young man from the company was here surveying to appraise my land. He said he would be back later with a proposal. But he never returned. I just received a court summons,” says the resettled rural worker, who has lived in the community since 1984.

Tio Julio has, along with his neighbors, organized resistance to call attention to Vale’s disregard for the community. After being visited by the mining company employee, he split his lot with other rural workers to gain more leverage in negotiations. It was no use. Now he will have to negotiate in court to sell 60% of his 48-hectare lot, in the community where he has lived since he was 13 years old – the company argues that his lot is in the mining company’s easement area. Vale asked for the part of farm that is near the Parauapebas River. Without access to the river, farming is not feasible.

“They watch us, they know we are organizing. Vale hates organized workers. That’s why they took me to court, and the courts didn’t listen to me,” he says sadly. Before Vale arrived, the small rural community was known for its vegetable production, chicken farming, and dairy. Vale provided no response as to why it went to court to ask for the rural worker’s land without attempting a prior negotiation.

Tio Julio and the residents of Vila Bom Jesus who spoke with SUMAÚMA want to be resettled in a new area far from the mines. The start of individual negotiations has, however, made this alternative less likely. Hope now lies with the independent investigation by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, which can provide evidence of the socioenvironmental impacts reported so long ago, and with action by Pará’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary, which has shown the Sossego operation’s nonconformance and failure to comply with environmental parameters. If environmental damages are proven, making agriculture and fishing non-viable and harming residents’ health, Vale may be forced to move the population to a new resettlement area. “We see our wealth leaving here every day on the truck, and all we’re left is illnesses and destruction,” says landless rural worker Edson Ramos. The company is not, however, considering any type of move.

Racha Placa: 50 families standing against Vale

The impact of mining in Vila Bom Jesus is mirrored in the destruction of another rural community, Mozartinópolis, located along one of the side roads accessing the S11D mine in Canaã. A community of rural workers from Brazil’s northeast who arrived in the 1980s, it was prosperous until the mine began to be installed, three decades later. There was electricity, running water, a school, and buses running to the city and to an office of the Agricultural Defense Agency of Pará.

When the installation began on the S11D mine, third-party employees working for the mining company started visiting the community. First, they hung up signs prohibiting hunting and fishing in the area, which was considered an outrage, since it was a community based on extractivism. The residents would then move the signs back, but they would return to the same place the next day. This dispute went on for weeks, until one resident took an ax to the unwanted notice. Hence the name Racha Placa, Portuguese for “sundered sign,” bestowed to the community that would be victorious in taking on one of the world’s largest mining companies.

Following the Vale social demobilization handbook, the company first took a census of the families in Racha Placa, promising to move them to other lands. While doing this, residents were notified that they could not make improvements to their homes or expand their crops, since they would not be indemnified beyond what had been provided. This recommendation sounded like a threat, and nothing ever came of the promise. Two years after the census, with no news of a move, Vale shifted to stage two: individual negotiations. The company persuaded the local pastor, who gathered up half of his flock. “They wanted to remove us from there at all costs, they even offered to give us a house in Canaã. But we’re rural workers. We want land to plant. We stood our ground,” says Marcos Vinicios Santos, 38, who came to the community from Bahia when he was seven, with his parents and six siblings.

Those who remained began to protest. Five times they shut down the Ferro Carajás, a secondary railway that follows a pear-shaped curve. Vale agreed to negotiate with the resettled rural workers, with Batista intermediating, and with Incra. In 2015, after almost 20 years of fighting and four years after the final resettlement, around 50 families were moved to the Américo Santa Resettlement Project, near Vila Ouro Verde, 45 kilometers from Canaã dos Carajás. The rural workers were each given a lot of around 22 hectares, with a two-room house, corral, and an artesian well – providing the community with water was one of the stipulations in the license to operate the S11D mine. All that was left of Racha Placa was the cemetery. Vale only lets former residents return on the Day of the Dead.