Prohibited outside of Brazil, multinationals’ agrochemicals contaminate the Amazon

SUMAÚMA obtained reports by the country’s environmental regulator, Ibama, which show the world’s biggest pesticide producers, like Syngenta and Bayer, keep “highly toxic” products, or considered carcinogenic by the European Union, in circulation

Rubens Valente, Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, Buriti River, Sapezal, Amazon

The village of Serra Azul sits a few meters from the Buriti River, in the heart of Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, in the municipality of Sapezal, around 510 kilometers from Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil. The river is calm and deep, its banks protected by dense vegetation and immense trees, including the species of palm tree that gives the river its name. At a few points, the clear water provides glimpses of schools of fish and rocks at the bottom of the river. Yet seven months ago, local Indigenous people stopped using this water for any of the village’s day-to-day needs. They don’t drink it, they don’t do laundry in it, they don’t bathe in it. Last September, for the first time, they had to bring in a 5,000-liter tanker to fill the water tank that supplies the community. The river washing onto the village’s banks had become dangerous.

The Indigenous people’s loss of trust in the Buriti River’s water was based on science. A wide-ranging study finalized in 2022 by the Collective Health Institute at the Federal University of Mato Grosso analyzed samples from medicinal plants the Indigenous people in the Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory grow, such as the white breu tree, Brazilian orchid tree, negramina tree, birici tree, mangava-brava tree, and licorice tree. The investigation, which was supported by the Native Amazon Operation), an Indigenist organization active since 1969, found agrochemicals in 88% of these samples.

“It would be hypocritical for us to keep drinking water that we know will… will cause something bad,” village leader Cleide Adriana Terena, the daughter of a Nambikwara father and a Terena mother, said. The study found 11 different agrochemicals in the samples, with four found per sample on average. Most are classified as insecticides (45%), followed by fungicides (36%), and herbicides (18%).

Exposure to agrochemicals is, according to the study, “associated with neurological diseases, cancer and birth defects, in addition to worsening respiratory and endocrine conditions.” In Nature, “the biggest impacts concern water contamination and high toxicity in bees and other pollinating insects.”

The discoveries went further. The study concluded that of the 11 agrochemicals found in the Indigenous Territory’s plants, five “are prohibited in the European Union (atrazine, carbofuran, chlorpyrifos, thiamethoxam, and acetamiprid).” The conclusion was unequivocal: “The presence of these agrochemical residues indicates environmental contamination inside of Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory.”

A study by non-governmental organization Public Eye shows countless reasons why these agrochemicals are banned in the European Union. In 2018, products were prohibited for posing risks of “death from inhalation, birth defects, reproductive or hormonal disorders, or cancer” (read more below). Despite their prohibition in the European Union, a range of agrochemicals are authorized for export, something studies out of Europe label as “hypocrisy.”

Research confirms agrochemicals banned in the European Union are widely sold and used in rural areas of Brazil. These products are made by behemoths like Syngenta, founded in Switzerland and acquired in 2017 by government-owned company ChemChina (China National Chemical). With operations in over 100 countries, Syngenta says it has 4,000 employees just in Brazil, where it has three factories. The company declared global earnings of 28.8 billion dollars last year alone. In 2024, as an investigation by SUMAÚMA showed, Syngenta was spared from paying the Brazilian government 4 billion reals through tax breaks, the same amount as the Environment and Climate Change Ministry’s budget for that year. The company has registrations for at least three acetamiprid-based products, as well as for ten others based on atrazine and another 22 based on thiamethoxam, three active ingredients banned by the European Union that were found in Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory. Acetamiprid is found in 62 products authorized in Brazil, while atrazine is in 85, and thiamethoxam is in 26 – these products are made by a variety of national and international companies, including Basf of Germany (a large company that uses acetamiprid), according to data from Agrofit, a database of information on agrochemicals registered with the Agriculture Ministry, and to data from the companies themselves. Syngenta is regarded as the biggest company in the Brazilian agrochemicals market. Basf is the world’s largest chemical group.

Another industry power player, Bayer, which was founded in Germany in the nineteenth century, sold a total of 6.2 billion euros of products to Latin America in 2024 alone. This figure relates to the Bayer Group’s “crop science” division, which involves “crop protection and seeds.” Worldwide, Bayer sold a total of 46.6 billion euros of goods in 2024, including its pharmaceutical division.

Brazil has played a fundamental role in the company’s bottom line in recent years. “The very positive overall sales development was mainly attributable to price and volume increases in Brazil at Fungicides, where business benefited particularly from the launch of FoxXpro™. We also posted an increase in sales at Herbicides,” Bayer’s report for 2019 reads.

Through Brazil’s Access to Information Law, SUMAÚMA was able to obtain the results of an assessment done by the country’s environmental regulator, Ibama, on the potential environmental hazard posed by FoxXPro™ fungicide, which is used on crops ranging from cotton to corn to soybeans. Ibama found FoxXPro™ is “very hazardous to the environment” and listed the following warnings: “this product is highly persistent in the environment; this product is highly toxic to aquatic organisms (algae, microcrustaceans, and fish).”

FoxXPro™ fungicide is made using the chemical ingredients bixafen, prothioconazole, and trifloxystrobin. SUMAÚMA found no records indicating the fungicide is prohibited in the European Union. Yet in 2024, the EU approved a regulation aimed at establishing “new Maximum Residue Levels for trifloxystrobin […] in various food products.”

Up until a few years ago, one of Syngenta’s most popular products in Brazil was paraquat, sold under the name Gramoxone 200. However, in 2017 the government prohibited sales of this product in the country from 2020 on. Since then, Brazilian farmers have begun to replace it with Diquat, which is sold under the name Reglone. An Ibama analysis of this product from early 2024 said it is “very hazardous to the environment.” The agency said it is “highly persistent in the environment” and “highly toxic” to worms and aquatic organisms.

By law, environmental regulator Ibama is responsible for assessing environmental impacts whenever a company registers an intent to sell an agrochemical in Brazil with the Agriculture Ministry. The country’s health surveillance agency, Anvisa, is tasked with evaluating impacts on human health – the agency did not, however, respond to requests made by SUMAÚMA through the Access to Information Law.

The European Union did not renew the license for use of Diquat in October 2018, after the health authority identified “a high risk to workers, bystanders and residents.”

Following an Access to Information Law request for environmental agency Ibama to provide the processes used to authorize agrochemicals indicated as being “highly toxic,” the Agriculture Ministry refused to release this information, alleging it is under “legal confidentiality of an industrial and business nature.” SUMAÚMA appealed, arguing the data holds an evident public interest, given the possible consequences these products have on human health, but the request was denied by the deputy secretary of agricultural defense, Allan Rogério de Alvarenga.

Fines and adulterated agrochemicals

Syngenta was in the middle of a scandal made public by Ibama in 2024. The environmental agency petitioned the courts, through a lawsuit brought by the Attorney General’s Office, to block 90 million reals of company money for the purpose of indemnifying environmental crimes as part of reparations for the alleged sale of adulterated agrochemicals.

According to the Attorney General’s Office, the company supposedly used the preservative bronopol “at levels nearly three times above the authorized amount” in producing the agrochemical Engeo Pleno, at the Syngenta plant in Paulínia, in the state of São Paulo. A product used on a variety of crops, including soybeans, corn and cotton, the Attorney General’s Office says bronopol “was also illegally added to the Karate Zeon 250 S and Karate Zeon 50 CS products, whose formulas did not even call for bronopol usage.”

In the lawsuit, environmental watchdog Ibama wrote in a technical note that the European Chemicals Agency, the regulatory body in the European Union, classifies bronopol as “very toxic” to aquatic life and warns it “causes serious eye damage, causes skin irritation and may cause respiratory irritation.”

SUMAÚMA asked Ibama about fines given to Syngenta and was told that in May 2024, the company “chose to convert its obligations into environmental services.” The environmental agency said, however, that “one of the suits did move forward, in order to assess application of restraint of right sanctions” – also known as alternative punishments, applied to limit or remove violator rights or activities. In May 2025, Ibama decided to cancel the results of an assessment on any potential environmental hazard posed by Engeo Pleno S.

An environmental assessment is one of the requirements for a product to be sold in Brazil. Ibama decided to do this new study because it found bronopol in an amount different from the analysis done for initial authorization, which is given by the Ministry of Agriculture following input from Ibama and national health regulator Anvisa.

Syngenta then appealed the environmental agency’s decision to cancel the assessment’s result and that appeal “is being considered by the competent authority.” The company is allowed to keep selling this product in Brazil during the appeal. A final decision has yet to be made. In addition to this administrative process, the lawsuit also remains active and has yet to receive a final judgment.

In relation to the bronopol case, Syngenta issued a statement in 2022 in which it confirmed a 2021 inspection by Ibama of its Paulínia factory “identified one nonconformance in the production process for specific lots of three agrochemicals.” The company said this is why Ibama decided a recall “was mandatory for the volumes of specific lots produced between September and November 2021,” which had not yet been used. Syngenta decided to include “additional lots in this recall” of the same three products and instructed farmers to return these products.

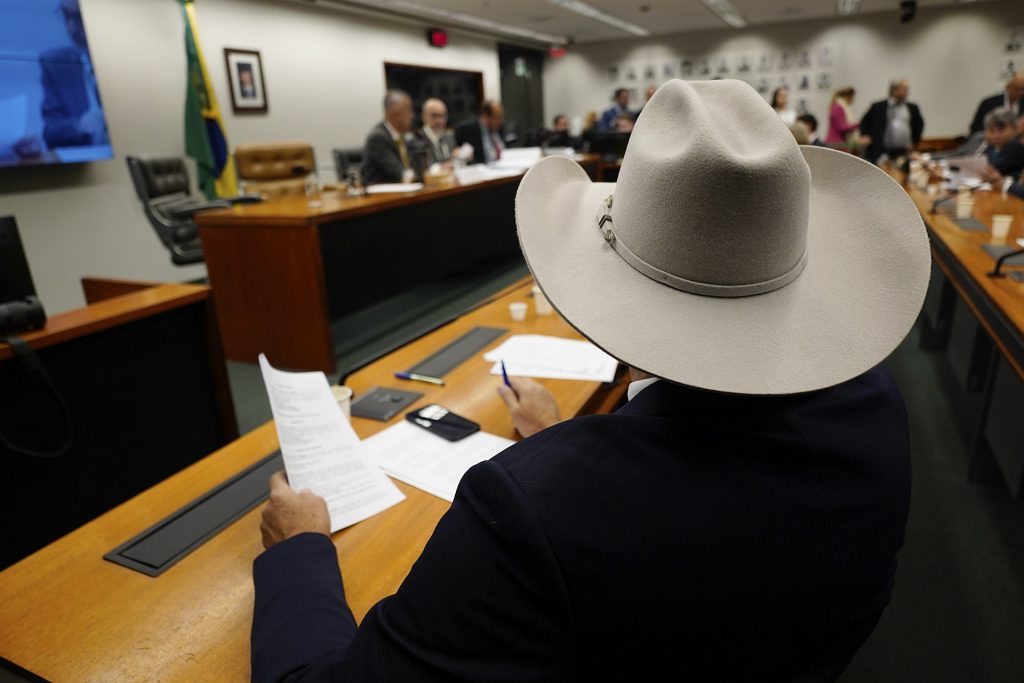

The corporate lobby machine

Maintaining the use of hazardous agrochemicals in Brazil requires significant political strength. In 2019, Syngenta, Bayer, and 50 other pesticide, “germoplasm (seedlings and seeds), biotech and bioinput” industry companies founded the non-profit CropLife Brasil, a lobbying group headquartered in the Chucri Zaidan business district of the city of São Paulo. The team has a total of 27 positions, including “regulatory managers,” and a government relations department. CropLife Brasil says it works to, among other things, “strengthen dialog with consumers, opinion-makers, and governments.”

A study entitled “Toxic Trading,” released by non-governmental organization Friends of the Earth in 2022, defined the entity as “one of the biggest agribusiness lobby groups.”

According to information published by CropLife Brasil on its website, its members represent “71% of the revenue in the agrochemical industry in Brazil.” “CropLife Brasil works to regulate the sector and foster the correct use of inputs for the country to continue moving forward in the agricultural sector,” the organization’s website says.

After being asked to comment on this story, Bayer’s press office in Brazil directed SUMAÚMA to CropLife Brasil, arguing that this would be “a matter involving the sector.”

According to the study by Friends of the Earth, both the Brazilian Agribusiness Association and CropLife Brasil, along with agrochemical trade group Sindiveg, which has 22 member companies, “lobbied in support of the Poison Bill,” a reference to Bill 6299/2002, which made it easier to use agrochemicals in Brazil.

“These companies and their associations lobby by directly targeting the executive and legislative branches of government, including by financing election campaigns for representatives of the [ruralist caucus]. They also lobby through campaigns designed to shape the policy narrative and influence the population at large,” the study’s authors write, which include university professors and researchers Larissa Mies Bombardi and Audrey Changoe.

Since 2019, Bombardi, the author of “Agrotóxicos e Colonialismo Químico” (Agrochemicals and Chemical Colonialism, loosely translated, published by Editora Elefante in 2024), has reported receiving death threats and says attempts have been made to disqualify her work, leading her to leave Brazil and work in Europe.

In a statement to SUMAÚMA, Syngenta responded that it “maintains a constant dialog with authorities, governments, regulatory agencies, the media, and society, aimed at information and debate based on science” and that it “conducts all of its dealings ethically and transparently.”

Syngenta did not, however, provide information on how much it has spent since 2022 on work connected or similar to lobbying. Bayer and CropLife Brasil also did not share this information. According to the “Toxic Trading” study, “major agribusiness associations which represent Bayer, BASF and Syngenta contributed around 2 million euros to support the lobby activities of the Instituto Pensar Agro.”

Created in 2011, Instituto Pensar Agropecuária, which currently has 58 agribusiness association members, is connected to the ruralist caucus, or Agricultural Parliamentary Front, and its goal is to “guarantee technical support and support for specific actions being considered in the National Congress, in addition to promoting interlocution with the judicial and executive powers,” as stated on its website.

Two of the agrochemicals industry’s biggest representatives are Instituto Pensar Agropecuária members: CropLife Brasil and agrochemical trade group Sindiveg.

Carolina Panis, a professor at the State University of West Paraná, is coordinating a study that for 10 years has been investigating the link between contamination from agrochemical use and cancer rates in the populations of 34 municipalities in Paraná. She told SUMAÚMA the agrochemicals industry has repeatedly denied the active ingredients in its products are connected to health problems in the region.

“They’re denialists. They say that’s not what it is, no. It’s pretty famous, this story about how they order studies that deny negative results for the industry, they sponsor researchers who say using agrochemical products is safe, that there’s no problem. This is more common outside of Brazil. Here, things are more hidden. They run free. Denialism exerts an impressive force, on everything. The person believes it as if it were a divine truth. Their advertisements suggest that without agrochemicals, the planet will starve, and farmers will go under,” Panis tells SUMAÚMA.

A recent report by UOL found that 196 of the proposals submitted by members of Brazil’s Congress were actually written by Instituto Pensar Agropecuária lobbyists. In October of last year, SUMAÚMA visited the institute’s mansion headquarters and mapped its lobbying activities through reporting, including the institute’s actions on the Chamber of Deputies special commission that discussed the Poison Bill from 2016 to 2018.

In the statement it sent to SUMAÚMA, Syngenta defended its practices in relation to the branches of government: “Throughout the meetings in which it participates, the company provides information on topics connected to defending the interests of farmers and Brazilian agriculture. This means Syngenta maintains a professional relationship with a wide variety of interlocutors, because it is a company that strives for ethics and to respect people.”

Speaking on behalf of Bayer, CropLife Brasil did not answer a question on its lobbying activities or pressure groups in Brasília (see more of CropLife Brasil’s statement at the end of this story).

‘How can we be free of agrochemicals?’

Around 1,500 kilometers from Brasília’s lobbyists, Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory is experiencing effects from agrochemicals used primarily in cotton production. The landscape along the state highway leading to the territory is overrun by large areas of the bushy crop.

When SUMAÚMA visited the region last September, the fiber had already been collected by machines and packaged into an array of plastic colors. These were then turned into enormous cotton bales, weighing around 2.5 metric tons each. Rows and rows of these blue, pink or green balls spread across the farms, waiting to be picked up by trucks that will carry them to the textile factories.

Cotton production in the Sapezal region relies on “various fiscal incentives,” according to the Federal University of Mato Grosso study, “such as the Fund to Support Cotton Crops (Facual), which provides tax exemptions ranging from 50% to 75%.”

According to the Federal University’s study, Mato Grosso was the Brazilian state “where area planted with cotton and cotton production grew the most in 18 years (from 2001 to 2019).” Sapezal and two neighboring municipalities, Campo Novo do Parecis and Campo Verde, were the state’s biggest cotton producers. From 2010 to 2019, the area planted with cotton in the region grew by 62%, while areas for planting rice fell by 70%.

The landscape abruptly changes upon reaching Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, where the plants typical of the transition between the Cerrado and the Amazon, with gnarled trees, still remain untouched and protected by the Nambikwara, Manoki, Paresi and Terena Indigenous people. All except for a portion estimated by the Indigenous Territory’s inhabitants to cover some 10,000 hectares, which some of the Indigenous people are now using to plant monocrops, particularly soybeans.

It is still a small part when compared to the entire Indigenous Territory, which covers 131,000 hectares, but there are evident economic pressures to increase the crop-growing area. Soybeans crops and other off-season products have become “an important source of income for the communities,” which depend on products like gasoline, diesel, oil, and gas for cooking.

In this context, the Federal University of Mato Grosso study and criticism of agrochemical use by the Indigenous people themselves have led to lots of reflection in Tirecatinga.

Geraldo da Silva Correia Terena, an Indigenous man, says that his activism in the 1980s was a determining factor in the positive outcome of the demarcation process of the territory, which was certified in 1991. Geraldo says that at that time, “all the neighboring farms had gunmen, and I fought with them.” Yet after the demarcation, these kinds of frictions disappeared. There are no more records of the territory being invaded by illegal cattle or crop farming activities, but the presence of the poison in the air and water has become a problem that, for Geraldo, is threatening its future.

“Today, thank God, we’re all neighbors. They [the farmers] respect us, we respect them. But now they’re disrespecting us with this agrochemical business. Agrochemicals are today, for us, a bad business. And now I ask you all, and I ask myself: How can we be free of agrochemicals? Because the cotton is less than 3 km from our area. At the edge of the river, both the Buriti and the Papagaio [rivers]… And now the rains, the downpours are going to start, everything washes into the water, right? And then, what’s going to happen to us?”

Geraldo says the situation grew worse seven or eight years ago, when cotton farming intensified in the region. “The cotton is destroying our fish, our game. Today, we aren’t seeing the game like we’re supposed to see it, like there used to be.” The bees are also disappearing. “Bees need 3 km of distance to look for nectar. I don’t have any more bees. I don’t have any jataí [bees], I don’t have mandaguari [bees], I don’t have borá [bees]. I don’t have a bee we call the arapuã. […] They’re disappearing, they’re all vanishing. Because of what? Because of the poison. And we hear that near the Indigenous Territory, [within] 3 km, 2 km, you can’t use agrochemicals. But what they most use is this. So what can we do?”

Leader Cleide Terena says the decision was made to ask the Federal University of Mato Grosso and the Native Amazon Operation to do the study after health problems appeared that are considered rare in the Indigenous Territory, such as respiratory system diseases, severe headaches, and even cases of miscarriages. “Lots of diseases arrived in our territory without us knowing what caused them. We were very worried about this situation. We saw a need to learn about what diseases agrochemicals could cause in human beings.”

Cleide’s mother, Terezinha Amazucaerô, lives with her husband elsewhere in the territory, along the Papagaio River, in an abandoned building that use to be the headquarters of the Utiariti religious mission, which operated a boarding school for Indigenous youth there until the 1990s. Unlike the residents of Serra Azul Village, the couple has to use the river’s water for drinking, bathing, and preparing food.

“There are lots of farms up there. Of course, everything they plant is washed down here by the pouring rain. But I don’t have any other choice. […] I don’t feel safe [with the water], because during the flood season, this here turns black. It gives you diarrhea, it makes you feel nauseous. But what am I going to do? The agrochemicals come from up there. And it all rolls down here.”

Across Mato Grosso, according to the Federal University of Mato Grosso study, 389 miscarriages were reported from 2000 to 2018 in the Indigenous population and the rate of mortality from birth defects is 3.9%, while in the non-Indigenous population, this rate is at 0.5% – although it is not possible to connect these cases directly to the use of agrochemicals. According to the study, respiratory issues among the Indigenous people, like pneumonia, bronchitis and asthma, worsen in the months of March to June, a period that coincides with “pest” control in the cotton crop (March to May) and the cotton harvest (June).

When the study compared data on kidney diseases in the municipalities in the Juruena River basin, where Sapezal is located, with Mato Grosso’s municipalities in general, it found “a growing and upward trend in kidney diseases, with an annual percentage change of 54% in the period (2008-2018)” for the state and 87% for the Juruena River basin.

Terezinha Amazucaerô, an Indigenous woman, dives into the Papagaio River, in Sapezal, which the community is concerned about using. Photo: José Medeiros/SUMAÚMA

Utiariti Waterfall, at the edge of Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, in the municipality of Sapezal, Mato Grosso. Photo: José Medeiros/SUMAÚMA

An Indigenous boy drinks water carried into Serra Azul Village by a tanker truck, avoiding the poisoned water in the river. Photo: José Medeiros/SUMAÚMA

Indigenous people build a traditional house in Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, in Sapezal. Photo: José Medeiros/SUMAÚMA

Serra Azul Village is suffering from agrochemicals being used near Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, in Mato Grosso. Photo: José Medeiros/SUMAÚMA

An aerial view of Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, in the municipality Sapezal, Mato Grosso. The farms behind the territory are expanding their fields. Photo: José Medeiros/SUMAÚMA

Agrochemicals are ‘a chemical weapon’ in agrarian conflict

The cotton dominating the landscape around Tirecatinga ranks fourth nationwide among the crops that most use agrochemicals, according to a 2021 study.

The Federal University of Mato Grosso study indicates that around 226 million liters of agrochemicals were consumed in Mato Grosso in 2019, 31 million (or 13.9%) were used on cotton crops. The study calculates that in Mato Grosso alone each inhabitant was exposed to 65.8 liters of agrochemicals in 2018. However, in some interior cities, like Sapezal, exposure per inhabitant may have surpassed 300 liters per year.

Some of the most recent cases of poisonings from agrochemicals in Mato Grosso were registered at a camp that is home to around 200 landless farm workers in rural Jaciara, around 150 km from Cuiabá, Mato Grosso. These cases also caught the attention of the Collective Health Institute at the Federal University of Mato Grosso.

In December 2024, Federal University of Mato Grosso researchers made a technical visit to the site. They found residents were suffering from illnesses as the direct result of agrochemicals being sprayed, “whether being sprayed directly and criminally on people, or from the drifting of aerial spray, or from toxic sludge carried into water sources.” People were found with “health problems in the respiratory tract, acute poisoning, skin and eye problems, and allergies, in addition to causing food insecurity and impoverishment based on the fact that the fruits and vegetables they were producing were killed.”

The study contained transcriptions of resident testimonials. “Before, they [the hired thugs] were armed, now they’re killing us with poison,” one person says. “They don’t want to kill pests, they want to kill us,” another reiterates.

The study by the Federal University of Mato Grosso asked for immediate action from the state government regarding health and oversight from the Office of the State Environment Secretary of Mato Grosso “to investigate any environmental crimes, especially in relation to the destruction of wellsprings and failure to comply with laws on minimum distances for spraying agrochemicals.”

The residents in the camp, named the Mestre I Parcel, relayed a series of reports to SUMAÚMA about what they called “chemical attacks,” allegedly perpetrated by neighboring farmers who lease land from an alcohol plant. The land had already been collected by Brazil’s agrarian reform agency, Incra, back in the 1980s, for conversion into the federal government’s agrarian reform program. However, a court ruling prevented the federal government from actually turning the area into a settlement, paralyzed by a legal mess that has dragged on for over 11 years. During this time, most of the land, which covers around 5,600 hectares, was leased to plant soybeans, corn, and cotton. Meanwhile, the landless farm workers continue to hold Incra authorization while they wait in their canvas tents on a parcel of just 500 hectares for the settlement to be established.

Our reporters visited the camp in September of last year. The community risked eviction following a June decision by justice Eduardo Martins of the Regional Federal Appellate Court of the 1st Region, who ruled in favor of a civil appeal filed by the alcohol plant’s owners. He ordered Incra to abstain from “promoting any settlement of landless workers in the Mestre I Parcel until a final judgment” was entered by the court.

The Prosecutor’s Office along with Incra, an arm of the Attorney General’s Office, lodged an appeal with the Regional Federal Appellate Court of the 1st Region against the injunction issued by the appeals court judge. In a hearing to consider the merits on October 15, another appellate court justice took the case under advisement and, with this, the case was suspended. The Federal Public Defender’s Office is also working to defend the landless farmers and is likely to make a statement to the National Council on Human Rights.

“It requires [that] documentary proof be considered that shows the Mestre I Parcel is federal property and that shows the illegal occupation sponsored by the appellees, so as to immediately grant federal ownership of the land in the Mestre I Parcel and the continued implementation of the Settlement Project for landless families of workers who have been camped in the vicinity for over 20 years, ” the appeal filed by the Attorney General’s Office with the Federal Regional Appeals Court for the 1st Region reads.

While the legal knot remains tangled, amidst substantial legal uncertainty, the families camped on the Mestre I Parcel are reporting repeated episodes of poisoning by agrochemicals, coercion, and threats from private security personnel. The landless workers have already filed several reports with the Civil Police, which SUMAÚMA has seen.

Two years ago, the director of the Department of Mediation and Settlement of Agrarian Conflicts at the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Agriculture, Claudia Maria Dedico, visited the Mestre I Parcel and found an “abusive use of agrochemicals, according to photographic records and testimonials collected at the site.” In the report, she also says that “After reports of various cases of diarrhea and allergies among the population, a desiccant agent [a chemical substance capable of absorbing water] was found to have been used at the Fazenda Bom Jesus farm, without any warning or precaution regarding the proximity to the community’s drainage (water source).”

Residents told SUMAÚMA about how uniport sprayers are used to scare and harass them on dirt roads. “It’s a chemical weapon. It was used on purpose. Just like on that day when they stopped in front of our buddy’s house. And the guy with the uniport kept spraying the leftover solution to hit the person living there. They lift the uniport arm up high [and spray a stream],” according to 55-year-old Mario Demko, a resident at the campsite who filed a police report against one of the leased farms in 2023.

In the second half of 2024, another campsite resident, Juliana Antônio de Souza, 42, had just left the camp in a car with her husband and three daughters (two 18-year-old twins and a six-year-old), on their way to Cuiabá. On the road, they encountered a uniport sprayer. Each time Juliana’s husband tried to move his compact car out of the machine’s way, its driver would switch lanes so that he was facing the family. As the vehicles were crossing paths, the uniport sprayed a white substance right on top of their car.

“It left our car all white. And it started burning here [in their throats]. It’s a very strong smell,” Juliana says. Experiencing respiratory problems and nausea, the family headed straight to a healthcare center where they were given prescriptions for medications and anti-allergy drugs. Juliana says that to this day her daughters have skin problems and that just the smell of the toxin makes her head start to “hurt a lot.”

Another camp resident, Maria Verônica Ferreira, 58, says she experienced a similar situation. As she and her husband were driving back from the market where she usually sells vegetables, the couple came across a uniport. For no reason whatsoever, Maria says, the machine shot a white substance onto their car. “They throw poison on us. My head was hurting. Then I just kept going to the doctor. He told me to do some tests, I even had a mammogram. So I could find out, learn what my problem was. I even had a test run in Brasília. The result hasn’t come back yet.”

Juliana’s mother, Catarina Antônio de Souza, 58, says the venom that is sprayed kills the gardens she tries to grow behind her tarp home. “The things planted, everything was poisoned to death. It burned all of our plants. My garden was completely burned by poison. I planted a vegetable garden, lettuce, carrots, beets. There was a time when it grew nicely. But there was a time when they applied poison, even by plane. And the cassava plants in my gardens, the things I planted, I would plant and plant and I could never harvest anything.”

After the episode of the “chemical attack” on the family’s car, Catarina says her granddaughter “was never the same.” “I can see that she isn’t well health-wise, no. She wakes up scared. I don’t know if it’s the poison. She becomes a restless girl, she covers her ears, she doesn’t want to hear a bunch of noise in her head. She cries a lot.”

The president of the União da Vitória Association of Small Farmers, Danilo Antônio de Souza, said the families are concerned about the quality of the water they consume, which is collected by two pipes near corn and soybean fields. The association surveyed 50 of its 160 families in November 2024 and found that 54% of them consumed water from the wellspring and 44% from the stream, with just 2% purchasing bottled water.

The residents surveyed said that they were suffering from headaches (32% of those interviewed), diarrhea (22%), allergies (14%), pneumonia (10%), itching (8%), and nausea (8%), among other symptoms. Through photographs and videos, the association documented how chemicals are sprayed by land as well as by air, using crop dusters.

Danilo says one of the association’s pressing demands is for blood tests to be done on all the families, to “identify the seriousness of the poisoning,” along with a wide-ranging analysis of the water and soil. The association president says the organization has already taken all of the reports to the Federal Police in Rondonópolis, Mato Grosso. SUMAÚMA contacted Mato Grosso’s Federal Police force, but did not hear back by the time this story was published.

Forbidden in the European Union, allowed in Brazil

In a statement to SUMAÚMA, CropLife Brasil argued the standards governing agrochemical use between the countries could not be compared, since there are differences among the “agricultural systems of production, weather and climate factors.” It went on to say that: “In Brasil, in tropical conditions, there is more pressure from pests and diseases than in the European Union, which has a temperate climate. This demands more intense phytosanitary management and the availability of different products to efficiently control pests. Therefore, the absence of authorization for an agrochemical in one country or economic bloc does not, in and of itself, mean that it is unsafe or inappropriate.”

SUMAÚMA looked into the current status of the five agrochemicals that the Federal University of Mato Grosso found in Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory in 2022: atrazine, carbofuran, chlorpyrifos, thiamethoxam, and acetamiprid. Atrazine has been banned in the European Union since the 2000s. It is “a common contaminant of water bodies, including drinking water, and so dangerous to both people and wildlife that it has been banned in more than 60 countries,” according to the Center for Biological Diversity, an organization headquartered in the USA. The center says atrazine “is an endocrine disruptor, meaning it disrupts the body’s hormonal processes. In fact it’s the poster child of endocrine disruptors, demonstrated to affect at least half a dozen hormonal pathways in humans. Its most notorious harm is to human fertility: It’s designated by California as a reproductive toxin, linked to reduced sperm quality in men and irregular menstrual cycles and suppressed ovulation in women. Atrazine is also linked to multiple birth defects in infants, such as gastroschisis, in which a child is born with their intestines protruding through their belly.”

In addition, “Researchers at the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute [also headquartered in the United States] have linked atrazine to multiple cancers, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and aggressive prostate cancer”.

Carbofuran has been banned in the European Union since 2008. A study by six researchers from universities in the states of Missouri and Florida, in the US, indicates contact with and ingestion of this substance “causes high morbidity and mortality in humans and pets.” They go on to say that “carbofuran exposure to eye causes blurred vision, pain, loss of coordination, anti-cholinesterase activities, weakness, sweating, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, [as well as] endocrine, reproductive, and cytotoxic effects in humans depending on amount and duration of exposure. Pesticide exposure to eye injures cornea, conjunctiva, lens, retina, and optic nerve and leads to abnormal ocular movement and vision impairment.” It ended up being banned in Brazil in 2017.

Another agrochemical, chlorpyrifos, was banned by the European Union in early 2020, and in February 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States revoked “all tolerances,” but it was put up for debate again after pressure from local farmers. Scientific studies indicate this substance “may pose serious health risks, including: damage to the proper development and later functioning of the brain (developmental neurotoxicity) from early-life stages onwards. This can translate into neurodevelopmental disorders such as working memory loss, autism, ADHD [or Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder] and decreased IQ.” Chlorpyrifos can also cause damage to DNA (genotoxicity), increasing “the risk of developing cancer.”

The agrochemical thiamethoxam has been prohibited for outdoor use in the European Union since late 2018, with an exception for “crops grown in permanent greenhouses,” with the Court of Justice of the European Union upholding this decision in 2023.

The substance puts bees in particular at risk. A Brazilian study from 2017 found thiamethoxam “reduced the survival of [bee] larvae and pupae and, as a result, lowered the percentage of emerging bees” and it “caused important physiological disturbances,” which could “affect colony development.” The study noted that the species of bee analyzed “plays an important role at the economic and environmental levels,” contributing “to more than 80% of total pollination in agriculture.” It warns of the “growing number of reports about declining bee populations worldwide.”

As reported by the French press last August, acetamiprid is authorized for sale in the European Union, but is banned in France. The substance remains under public scrutiny, with reports that the European Union recently decided to reduce “acetamiprid levels in food, after letters and evidence were sent” by PAN Europe, a non-governmental organization.

On January 7, 2026, France announced it was limiting imports of agricultural products, especially ones from South America, that “receive treatment with agrochemicals prohibited in the European Union.” Observers saw the measure as a response by the French government to pressure from French farmers who are opposed to signing the European Union-Mercosur trade agreement.

What the global agrochemical giants say

In a statement sent to SUMAÚMA, CropLife Brasil said its own survey found that “most of the active ingredients used in the manufacture of agrochemicals are also authorized in the biggest global markets.”

“Of the 319 substances approved in Brazil, just 57 (18%) are not registered for use in the USA and European Union. On the other hand, of the 364 registered in the US – a number higher than in Brazil – 125 (35%) are not registered for use in Brazilian agriculture. The same is true of the European Union: of the 254 approved, 86 (33%) are not found in the Brazilian market. The data strongly shows the decision to approve substances considers commercial factors, local demands, and specific needs in each agricultural context,” CropLife Brasil said in its statement.

According to CropLife Brasil, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations noted that in 2021 Brazil was “ranked 41st globally in application of agrochemicals per hectare – a rate equal to around half of what was found in smaller markets, considering total planted area. This indicator is evidence that Brazil’s proportional use is moderate and compatible with the world’s biggest agricultural powers, in opposition to the recurring perception of excessive use.”

A study done by the Food and Agriculture Organization, which covers the period of 1990-2022, concluded, however, that Brazil “was the world’s largest user of pesticides in 2022, with 801 kt [or metric kilotons] of pesticides applications for agricultural use. This was around 70 percent higher than the United States of America (468 kt), the second largest user.” The 801 metric kilotons cited in the study are equal to 801 million kilograms.

In the same statement given to SUMAÚMA, CropLife Brasil wrote: “The sector is aware of its responsibility to promote more and more sustainable and innovative agriculture, which joins productivity with environmental preservation and the protection of human health, which is why it maintains a continued commitment to promoting good agricultural practices based on the correct and safe use of technologies in the field.”

In a statement, Syngenta also claimed “various factors can determine whether a substance is registered in one country and not in others, such as crop differences, the rate of pests and diseases, the existence of more innovative products, the costs of regulatory studies, rates of registration versus the need for that active ingredient, climate and soil issues, and other particularities.”

The company said “the fact that a particular active ingredient has not been registered or approved in a country does not mean it underwent an assessment that prohibited it because it posed health or environmental risks.” “In most cases, ‘non-approval’ regards three types of substances: those that were never assessed; those for which registration was not renewed; or those for which the applicant company did not meet bureaucratic requirements, such as failing to pay fees to maintain registration. It is therefore necessary to clearly differentiate each situation and its context.”

Basf said all its products are “widely tested, assessed, and approved by the competent authorities, according to official approval procedures established in the respective countries.” The company also said it “stresses the safety of its solutions, when used correctly, according to package instructions and guidelines for responsible use” and it establishes practices that support responsible and ethical management across the lifecycle of its products. “It is important to understand that there are big differences among crops, soil, climate, pests, diseases, and agricultural practices around the world. That is why Basf adapts its solutions to the needs of each region where it operates,” its statement said.

CropLife Brasil, indicated by Bayer to answer SUMAÚMA’s questions, as well as Syngenta reiterated that for a product to be used in Brazil, it must undergo assessment by health agency Anvisa, environmental agency Ibama, and the Agriculture Ministry. “These regulatory agencies can request reassessment of a product at any time, whenever new evidence is found by the international organizations that Brazil is part of. Another important point to note is that after registration is granted by the Agriculture Ministry, Ibama and Anvisa, the state of Amazonas also requires state registrations. However, Syngenta does not register products in the state of Amazonas precisely so that they are not used there,” the corporation says.

In relation to lobbying activities in Brasília, Syngenta stated that it “maintains a constant dialog with authorities, governments, regulatory agencies, the media, and society, aimed at information and debate based on science.” “Syngenta conducts all of its dealings ethically and transparently. Throughout the meetings in which it participates, the company provides information on topics connected to defending the interests of farmers and Brazilian agriculture. This means Syngenta maintains a professional relationship with a wide variety of interlocutors, because it is a company that strives for ethics and to respect people.”

The view of those who should protect life

SUMAÚMA reached out to the Office of the Environment Secretary of Mato Grosso, which said it “works to monitor rivers where water is suspected of contamination by agrochemicals, as well as to combat deforestation and other activities,” but that requests for information on agrochemicals should be directed to the Institute of Agricultural Defense of Mato Grosso. This institute did not, however, comment when contacted.

In Brasília, Indigenous affairs agency Funai said in a statement, “the presence of agrochemicals on medicinal plants in Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory is a reflection of its surroundings, which are highly dedicated to growing cotton and other crops on a large scale.” “Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, as well as the Paresi and Utiariti Indigenous Territories, in an area contiguous to the Tirecatinga Indigenous Territory, are immense ‘filters’ of agrochemical in native Cerrado, in a region rich in wellsprings. The situation would be worse if they were not there.”

The Indigenous affairs agency said it was unaware of the study done by the Federal University of Mato Grosso, but it “sees the situation with extreme concern for the subsistence of the Indigenous populations exposed to completely contaminated bodies of water.” “The increased use of agrochemicals concerns Funai, in the Amazon as well as in the rest of the country. This concern regards not just permitted agrochemicals, but also agrochemicals newly authorized in the country as well as ones that are prohibited, but that illegally enter through border regions, at times crossing through Indigenous Territories.”

In a statement, Ibama said it does not have the “legal competency to authorize the use of agrochemicals in national territory,” since “authorization of the use, sale, and oversight of agrochemical application is the responsibility of state environment agencies, as established by Law no. 7.802/1989 and Decree no. 4.074/2002.”

The agency, which is connected to the Environment and Climate Change Ministry, says it acts “exclusively on the environmental assessment stage for registration purposes.” “This analysis is aimed at identifying the possible impacts the products have on the environment, fauna and flora, before registration is granted by the competent agencies. After this stage is finalized, authorization for use and local enforcement are the states’ responsibility, through their environmental secretariats or institutes.”

In a statement to SUMAÚMA, the Health Ministry confirmed three villages in the Sapezal region “regularly receive a supply of potable water.” “To strengthen monitoring of this topic, the Office of the Indigenous Health Secretary created the Committee on Mercury, Agrochemicals and Other Environmental Contaminants, tasked with coordinating primary care and sanitation actions and strategies related to contamination in Indigenous Territories.”