“The company took our wealth”: the struggle of Ribeirinhos who lost their river to Alcoa

A US mining company with a history of environmental disasters wants to extract bauxite from the Serra do Uxituba, in Pará state, an area of conserved Forest and archeological sites

Hyury Potter (text) and João Laet (photos), Amazon River, Juruti, the Amazon – July 2, 2025

In the Amazonian winter, torrential downpours make for a treacherous climb up the Serra do Uxituba in Juruti, a municipality in the west of Pará state. Dona Maria Auta Garcia’s calm, steady steps help the 69-year-old tackle the trail after the rainstorm. With a straw hat, worn from daily use, and a paneiro—a basket made from the leaf of the ambé vine—the woman, born and raised in the region known as Juruti Velho, walks through a wall of açai and cupuaçu trees in the company of centuries-old Brazil nut, sumaúma, and andiroba trees.

From this spot in the Serra do Uxituba, the Amazon River can be seen 90 meters below, surrounded by Forest with almost no signs of degradation. The conversation stops to make time for catching a breath after the steep hike. Squirrel monkeys are visible in the treetops. The thick woods on the hillcrest give way to a small, planted area, well tended by Dona Maria and her husband, João Felix Garcia, 68, a farmer who spent his whole life eating what grows from the ground.

For as long as they can remember, Dona Maria and João’s lives have been structured around climbing and descending these hills, around the cassava that sprouts and the banana trees that give fruit—a life connected to the rhythms of surrounding Nature, now at risk of disappearing in the face of greed for what is below the soil.

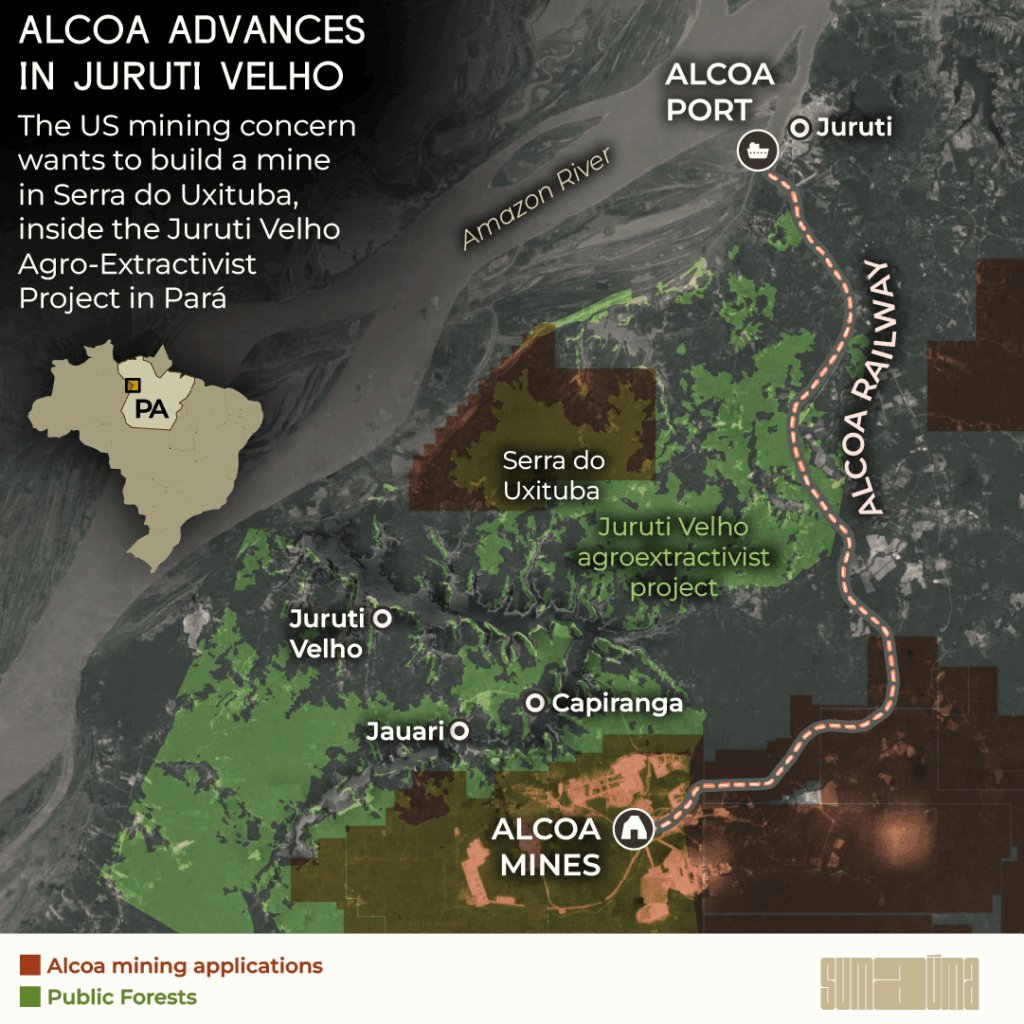

Alcoa World Alumina Brasil, the local arm of the US-based multinational, wants to dig up the soil to extract bauxite, the ore that yields aluminum. If the company achieves its goals, 9,000 hectares of these hill lands, an area larger than Manhattan, will turn into a gaping, lifeless crater. And Alcoa is in a hurry because the bauxite mines it already operates in the area will run out in a few years, according to their projections. That’s why, per an investigation opened by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, there are indications the US multinational could try to override the will of the traditional Ribeirinho communities, though the company denies this (read more below).

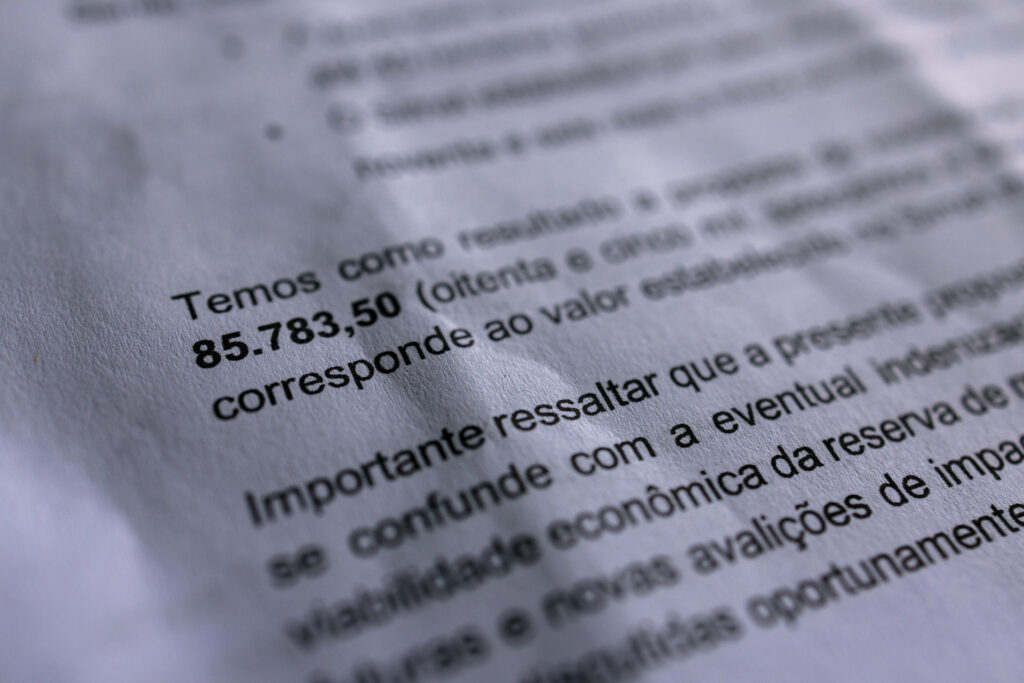

In November 2024, the transnational corporation delivered a proposal to the people of Juruti Velho. It offered $14,800 to explore for bauxite on 45 hectares of the Serra do Uxituba. The money would be given to the Association of Communities in the Region of Juruti Velho (Acorjuve), an organization that represents the 71 communities in the area and around 10,000 individual residents. The search for the ore would mean digging 593 holes, which on their own would already pose a great risk to Nature.

But all 71 communities said “no” and rejected the mining company’s offer. “First [we’d] set fire to their projects and then leave,” Dona Maria joked, imagining the company arriving in her backyard. The community’s resistance was only possible because, two decades earlier, they fought for the creation of the Juruti Velho Agro-Extractivist Settlement Project, recognized by Brazil’s land reform agency Incra in 2009. Since then, in order for anyone to drill even a centimeter into the subsoil, the local population must be consulted.

Dona Maria and those who resist alongside her know what it would mean to allow Alcoa into the Serra do Uxituba. Decades ago, they witnessed destruction that eroded the lives of other Ribeirinhos not far away.

The looming past

Born and raised in the Capiranga community, located on the left bank of the Juruti Grande, Gilson Pimentel, 72, remembers the 1960s, when there were only four Ribeirinho communities in Juruti Velho.

His hands tell the story of his past. There are marks from cuts and calluses from collecting Brazil nuts, his source of income in his youth. Harvest took place between January and May, and the main customers for the nuts were Jewish people who lived in Óbidos, around 100 kilometers from there, recalls Gilson, who everybody calls Lazico. “I’d take my coffee with me [to the harvest site] in a glass Montilla rum bottle,” Lazico said with a hearty laugh. Next, he showed us a straw basket and proudly told us how much he could stand to lift. “I used to carry up to five cans in the basket.” Lazico said. Each can held five pods, the hard shell of the fruit, which contains 12 nuts. He would haul almost 50 kilograms on his back.

In the 1990s, Lazico noticed a change. In addition to the occasional buyers who came to the community, he began to observe the activities of employees from various companies, drawn to the region because geologists had detected ore in the 1970s. The bauxite reserves in western Pará attracted the interest of both public and private mining companies.

But it was only in the early 2000s that things started happening in Juruti. Lazico was told he could make extra money by digging holes for Alcoa—up to 28 meters deep and 80 centimeters in diameter. Workers climbed down with buckets to bring the red rocks to the surface, where they were analyzed by engineers in their search for the ore.

“Inside the well, the smell of gas was really strong. There was a fan to get rid of the stench,” Lazico said, drinking coffee and eating beiju crepes made with cassava he grew himself. He grows serious when he describes the destruction wrought by mining, which he unknowingly helped inflict on his own land for some extra money. “They never told us they’d deforest,” he said. “They started by clearing the land for the mining. They ran tractors through to take out the smaller trees and then collected the hardwood for sawing and storing. The Brazil nut trees were the last to be cut,” he said.

Alcoa’s lights came on in 2009, when the company began producing after the period of exploration. But before that, it faced protests by the people who lived there and, after pressure, had to sign a financial agreement with the communities: compensation for damages of $7 million, or around $1,650 per family—finally paid in 2023—plus royalties that average $45 per month for each of the 4,060 families in Juruti Velho. Despite the trivial amount for the company, families interviewed by SUMAÚMA said they haven’t received anything since February 2024. When asked if receiving money from the mining company was worth it, Lazico brought up the Brazil nut trees that had been cut down. “It was much better before, because no matter how much the money might be, it runs out.”

The Brazil nut grove used to be on the other side of the Juruti Grande, where now the sky is lit up at night. The bright glow could easily be mistaken for a city in the middle of the Forest, but it’s just part of the gigantic complex built by Alcoa, which includes a processing plant and tailings ponds extending across some 10,000 hectares. The noise of the machinery that processes and transports the ore is constant. Analysis of satellite data shows the US company’s site emits more light than Juruti Velho, a community with 7,000 inhabitants, second only in size to Juruti proper. This enormous facility is only two kilometers away from Lazico’s community.

The year Alcoa started its operation, 2009, was the last year that Lazico was able to collect Brazil nuts. Without the income from the harvest, he lives off his minimum-wage pension, but he doesn’t sit idly around. He only had time to be interviewed at night because he spent the day fixing the community’s water pump. Without it, residents can’t bathe or cook, despite living next to a tributary that feeds into the Amazon River.

“The water makes you itch,” multiple people said. According to them, Alcoa spills are the cause.

River dwellers without a River

The tucunaré is a fish native to the Amazon Basin. It grows to between 30 and 60 centimeters, and the fishers of Juruti Velho swear it loves moving bait. That’s why, in order to catch one, fishers throw a hook in the water and go after it in a rabeta, a small motorboat about the size of a canoe. That had been the plan for 42-year-old Beto and Nildo, as Alciberto Sousa and Adenilson de Souza are known, on the morning of December 26, 2020, when, a few minutes after leaving the community of Jauari, also a part of Juruti Velho, they noticed the River had changed. The dark water had been replaced by a “yellowish color, like tucupi [a bright yellow sauce made from cassava juice],” Beto said.

They kept going. First they followed the course of the Juruti Grande and then the Jaurai Central, until they saw mud flowing down the Capiranga Plateau, starting about 90 meters above the water, where Alcoa had built a dam to hold tailings, which the company claims are “not toxic” and “pose no danger to the environment.” Unable to withstand a rainstorm the night before, the structure the company had built failed, spilling red clay into the waterways that feed the Amazon River. “The mud smelled of grease, diesel. I think that’s because of the machinery that goes back and forth over the hills,” Beto said.

The Ribeirinhos said the mud took over the small River, killing tucunaré and other fish they had intended to catch. Furthermore, the water became unusable even for domestic purposes. In the following months, the residents depended on bottled water and food assistance from the company.

Residents avoided swimming because many of them reported itching after contact with the water. Mining turned them into Ribeirinhos without a River.

SUMAÚMA was in the Jauari community after a big day-long storm. When it rains really hard, a group from the community goes together by boat and checks if there has been a new breach in the tailings dam. Five years on, they are still afraid that more mud will choke the River.

The Jauari Central is narrow, and there are many sections where access is only possible by small boats carrying a maximum of five people. Around 30 minutes downriver from the community, the characteristic dark green waters give way to a reddish, muddy tone. Even the foliage is coated in the red dust that falls from the tailings dam atop the plateau. But Nature resists, flaunting her aquatic plants.

Nildo guides the boat along the edge of the Capiranga Plateau and vents his frustration as he points out that the collapse occurred in places where the tailings dam was less than five meters away from the edge of the hill: “The company got rich and took our wealth.”

Beto, who is vice president of the Acorjuve community association, agrees with the criticism. After the residents protested, and four years after the spillage, Alcoa paid compensation of around $20,000 per family in 2024, according to both the residents and the Pará State Public Prosecutor’s Office. The fisher said the money doesn’t come close to covering the permanent damage the mining company did to the region. “It’s not enough because what they’re killing won’t ever recover,” Beto said.

The Jauari and Capiranga communities were the most affected by the spilled tailings, but as the fishers pointed out, the Juruti Grande carried water contaminated with leaked substances to other Juruti Velho communities. A few weeks later, another leak was detected by residents of Capiranga, and slurry consumed another waterway in the region, the Guaraná, where the mining company sources water to wash the ore.

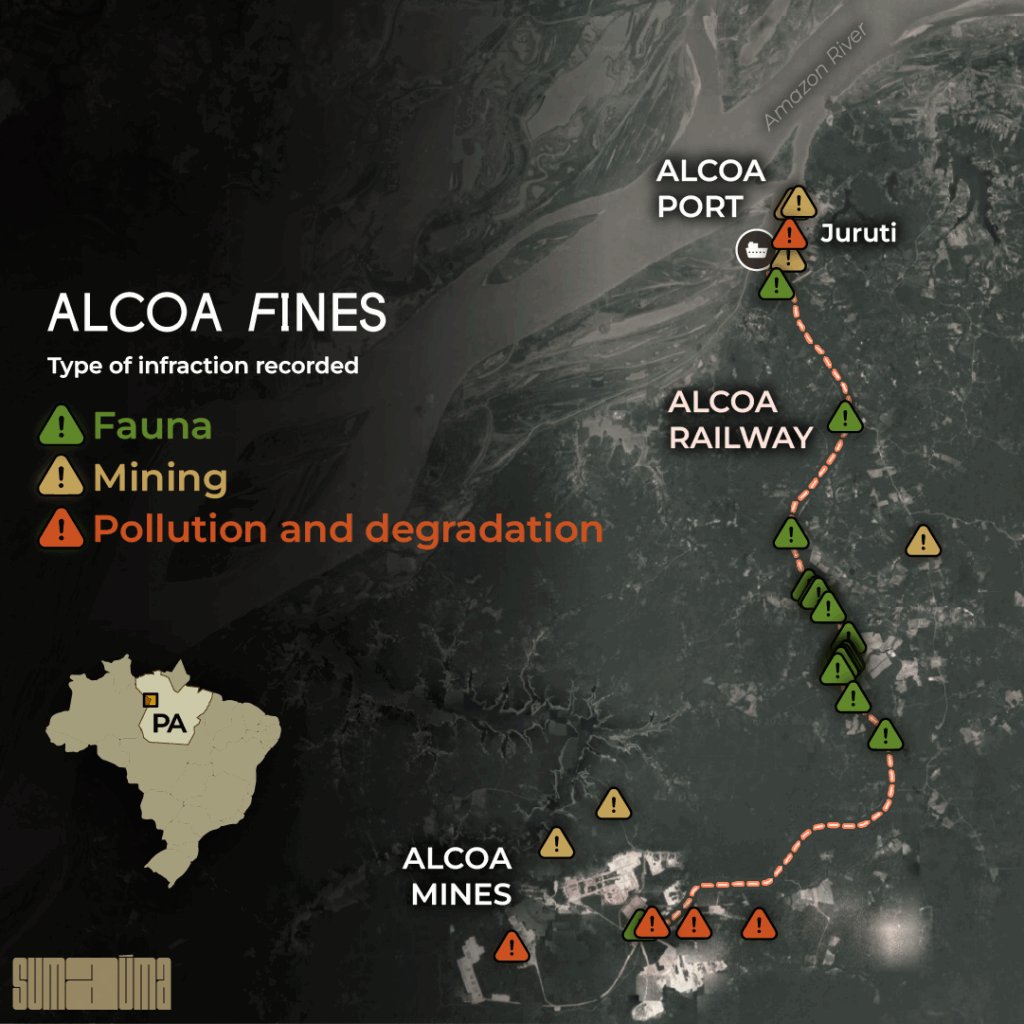

Pará’s state department of the environment fined Alcoa three times for the spills, totaling almost $900,000, but the paper trail indicates the company has still not paid for the environmental damage it caused. According to the state government’s transparency website, the department has imposed 49 fines against the company since 2018, most of them for environmental pollution, such as the cases of the spilled tailings, and for the deaths of animals run over by the train that carries bauxite from the mines to Alcoa’s port.

In a statement, the Pará environment agency said the fines imposed on Alcoa total approximately $1.94 million and that the company has paid less than a quarter of that amount, or around $440,000. Other fines are being appealed, including the three imposed for the 2020 and 2021 spills. Even with a revenue of $2.8 billion since the start of its Juruti operations, the company has resisted settling its environmental debts with the Forest in the Lower Amazon region. Asked about the spills, a spokesperson replied that its “operations in the territory are based on best practices in the sector.”

In a report filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission in May 2021, five months after the spills, Alcoa blamed the tragedy on rain and tried to calm investors by saying they were “disputing these fines at the administrative level” and that the “incidents” were “soil erosion events” that hadn’t “involved or affected bauxite residues [tailings] or impoundments.”

After the “incidents” and “events”—terms used by Alcoa in its official statements to refer to the tons of mining tailings dumped into the environment—the US multinational installed sirens and signs indicating evacuation routes in some communities. All the leaks from late 2020 to early 2021 were discovered by the Ribeirinhos themselves, who had always found the language used by the company peculiar.

“They came to the community calling it an ‘event.’ We questioned that word, ‘event,’ because an event for us is a party,” said Geane de Souza, 27-year-old resident of Jauari. Ever defiant, she inherited her courage from her mother, Robelita Souza, 45, one of the community leaders at the forefront of the protests to get Alcoa to compensate Ribeirinhos for the environmental crimes that changed their way of life.

“We don’t have any more fish or wild game. Things have gotten really hard,” says Robelita, who, despite living on the shores of the Juruti Grande, admits she’s afraid of using the water. “It’s been five years since the accident, five years since I’ve gone in swimming,” she said. She stresses that the problems didn’t only come from the spills: “It’s not as cool as it used to be. It’s really hot here now because of the deforestation done by the mine,” she said. “If only we could go back in time.”

From one hilltop to another

The recent spills in Juruti Velho and the tragedies in Mariana and Brumadinho, Minas Gerais—both of the latter linked to Brazilian mining giant Vale—have served as a lesson for the Ribeirinhos who live near the Serra do Uxituba, the new plateau Alcoa has its sights on and where Dona Maria makes her home. Residents know they won’t be able to go back in time, so now is the time to resist. When the association president submitted the mining company’s offer at a meeting in November 2024, the people in attendance were unanimous in rejecting the US group’s proposal to expand exploration into other hills in the region.

From Uxituba to Jauari and Capiranga, where Alcoa is already operating, it is a 40-minute trip by voadeira, the speediest little motorboat on Amazon rivers. The traditional homes in the area, some standing on stilts, are nestled at the foot of the hills and along the shores of lakes whose waters feed into the Amazon. Some of the homes blend into a mighty wall of açai palms, one of the community’s sources of income. Residents speak proudly of the springs that are born on the hillsides and flow straight into their water reservoirs, no need for pumps. Gravity helps bring them cold, clean water, a luxury in a region where the only way to take a shower or have water in your tap is with a generator.

A son of Uxituba, Rui Matos de Moura, 77, has lived here longer than almost anyone else—so long that the floodplain Forest by his house is known as Rui’s Igapó. A tall jokester with a thin face and Roman nose, he makes hot chocolate by shaving a bar of pure cacao into a pot and heating it up with water, sugar, and powdered milk.

Cocoa is a source of income for his family, who also extract andiroba oil, harvest açai, plant cassava and yams, and hunt and fish. Most of what they collect is for their own consumption, and the rest they sell or trade with neighbors. To this day, the tight-knit community holds puxiruns, a word that means “coming together for the common good” in the Indigenous language Nheengatu, from the Tupi-Guarani family.

The week before, a ten-story-tall andiroba tree toppled onto a section of his son’s home, next to his. Relatives and neighbors quickly got together to fix the demolished roof. “We help each other. Sometimes our community might fight, or gossip, but with something like this, we lend each other a hand,” Rui says.

The kitchen in his wooden house overlooks the Igapó, or floodplain Forest, where Rui claims in jest he can fish. Hanging on the wall among family photos—12 children, 20 grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren—are images of St. George and Pope Francis, placed there by his wife, Maria das Graças, 74. “I couldn’t sleep the night they said they were coming to make the offer [to explore for bauxite],” she says.

For Rui, the water coming from the hills will be the first victim of Alcoa’s ambitions. “If they mine the ore, our water is gone,” he says. “Because water is also created by the Forest. Where you cut it down, it dries up,” he warns. In the early 2000s, the 77-year-old fisher did drilling in Capiranga, alongside his friend Lazico. Today, he looks at that work in a different light: “We were planting a cancer in our region.”

Rui still harvests Brazil nuts in the Uxituba hills but remembers the last time he visited the Serra do Capiranga, where Lazico’s trees used to stand. Now the only thing that comes out of the ground there is red ore. “We used to walk in a huge Forest, go camping there. The trees were really thick,” Rui says.

Herena Maués, a prosecutor with the agricultural tribunal in Juruti, also remembers Alcoa’s impact on the town. In 2006, the municipality’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), based mainly on trade in Forest products, was $46 million but 15 years later had reached $256 million. The city gained more infrastructure, such as a hospital, schools, and new offices for public agencies. However, studies show the economy is highly dependent on Alcoa, which raises concerns about the future of the municipality when the bauxite runs out.

The population also grew during this same period, jumping from 34,000 in 2007 to 54,000 in 2024, and this prompted a series of social problems. In 2007, when the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office filed a lawsuit to have Alcoa’s environmental license cancelled, one of the arguments was the outbreak of viral hepatitis that may have been caused by the lack of sanitation at construction site lodgings. “Juruti is an open vein. If you look at the social disruption the company has caused, it has been tremendous,” the prosecutor says.

Incomplete proposal

The bauxite coveted by the US multinational lies at a depth of around 20 meters in the Serra do Uxituba. The mining application submitted to Brazil’s National Mining Agency on January 31, 2020 (less than four months later, the federal body had granted permission) is for exploration, a phase prior to the actual installation of a mine.

The Serra do Uxituba is Alcoa’s plan for continuing to profit from the region’s lucrative subsoil. Last year alone, Alcoa earned $180 million by extracting 6.2 million metric tons of bauxite from the land—a money mine that seems to be drying up. In late 2024, in a report issued on the US stock exchange, the mining concern estimated that the three mines it currently operates in Juruti hold 64 million metric tons of bauxite reserves. If Alcoa continues to extract bauxite at the current rate, the ore will only last another ten years.

But the exploration licenses granted by the federal government pertain only to the subsoil, without any validity over the surface, where the Ribeirinhos live and raise their crops. For this, the company still needs residents’ permission.

Alcoa’s proposal, which was presented by the community association Acorjuve and seen by SUMAÚMA, offers Acorjuve $14,746.27 to be allowed to deforest 45 hectares on the Medeiros plateau, as the company refers to what the Ribeirinhos—who have lived there for decades—call the Serra do Uxituba. However, nowhere does the text explain that residents would have to leave the homes where they have lived their entire lives, should Alcoa confirm the presence of ore and then put in a mine.

Alcoa’s proposal also mentions its intention to form a working group to “conduct the consultation and consent process for mineral exploration,” which is a legal requirement. However, in an official document sent to the National Mining Agency, the tone is not so warm toward the communities. On March 23, 2023, the mining company cited Acorjuve’s previous refusal to grant access to the area and appealed to the federal agency to “mediate, conciliate, and rule on conflicts between the agents involved in the mining activity.”

The document was attached to a civil inquiry opened by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in Santarém in November 2023 to investigate Alcoa’s offensive on Uxituba lands. Federal Prosecutor Paulo de Tarso, responsible for the inquiry, asked the company for information and highlighted some of Acorjuve’s initial complaints, such as “the lack of concern with the area’s water resources” and the mining company’s plans to keep as an option “the legislative alternative of asking the judge to order an expert assessment to determine the amount of compensation” should it fail to reach an agreement with the residents.

The possible relativization of the free, prior, and informed consultation with traditional peoples, a requirement under Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, shows that Alcoa hasn’t learned from past mistakes. In 2018, the company attempted to explore for bauxite in PAE Lago Grande, an agro-extractivist project in the neighboring municipality of Santarém, but was blocked by the federal courts. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has accused the multinational of entering community areas for exploration purposes without requesting authorization through the proper legal process. Alcoa claimed it had residents’ permission but submitted no documents proving any consultation had taken place, and residents say none ever did.

At the time, the multinational alleged in the 2nd Federal Civil and Criminal Court of Santarém that, in its understanding, the consultation that is provided for under the international agreement to which Brazil is a signatory consisted of a simple “survey of opinions.” In his ruling, published in October of that year, Judge Érico Freitas Pinheiro corrected the company, emphasizing that “the text of the convention is clear in stating that the objective of the consultation is achieving agreement and consent to the proposed measures.”

In a statement sent to SUMAÚMA, Alcoa said “since the beginning of [the company’s] operations in Juruti, it has prioritized open, ongoing dialogue with all communities directly and indirectly impacted by the company’s activities.” The mining concern also said, “the company’s first step toward holding a free, prior, and informed consent with community residents is to issue an expression of interest to the community association.” The company also pointed out that it “has already invested over $14.8 million in initiatives related to health, education, job and income generation, connectivity, public safety, and social assistance in both urban and rural areas” where its mines are operating. This is less than 1% of the $2.8 billion the company has earned from operations in the region.

As to residents’ complaints about not receiving royalties since February 2024, the company said all such transfers have been made.

Acorjuve receives the money from Alcoa and then passes 60% to residents while keeping the remainder to cover the costs of the organization itself and collective actions in the community. However, many residents of Juruti Velho complain they haven’t been paid or given information about what the association does with the money it retains.

These controversies over the lack of transparency on the part of Acorjuve’s management are longstanding. Since the association was founded in 2004, it has had only one president, Gerdeonor Pereira, something criticized even by the Catholic Congregation of the Franciscan Sisters of Maris Stella, who have been active in Juruti Velho since the 1970s and played an important role in the earliest resistance movements against Alcoa in the early 2000s. In 2013, the nuns stopped supporting Acorjuve because they believed the mining royalties were being mishandled.

Despite three weeks of attempts to contact him, Gerdeonor Pereira did not respond to the matter of the residents’ complaints.

1970s

Start of technical studies on prospecting for bauxite in Juruti. The first mining application is registered with the National Mining Agency by US-based Reynolds Metals Company (RMC) in 1975.

Starting in 1975

Through subsidiary companies Mineração São Jorge Ltda and Matapu Sociedade de Mineração Ltda, RMC conducts various studies in the Juruti Velho region. Ribeirinhos even work on the dig sites.

2000

RMC and its subsidiaries are bought by Alcoa, another US company, then facing accusations in the US involving its asbestos production.

2005

Residents establish the Association of Communities of the Juruti Velho Region (Acorjuve). They also begin a territory recognition process with Brazil’s land tenure agency Incra.

2005

The government of Pará grants Alcoa its first environmental licenses. In the same year, federal and state public prosecutors file a public interest civil lawsuit calling for annulment of the environmental licenses.

2007

At public hearings to discuss the impacts of the bauxite mine, residents report pollution of tributaries. Months later, Juruti has an outbreak of hepatitis A, triggered by river pollution allegedly caused by Alcoa’s activities in the region, according to the Pará government. The federal and state public prosecutors again call for cancellation of the mining company's licenses.

2007

A Working Group is formed to monitor the Juruti Project, made up of members of Incra, the Pará environment department, the National Mining Agency (known at the time as the National Department of Mineral Production), and other federal agencies.

February 2009

Residents of Juruti Velho hold a protest against Alcoa's mining operations during the World Social Forum in Belém.

March 2009

After protests, Alcoa and Acorjuve reach an agreement, and communities receive the right to 1.5% royalties on bauxite extraction. They also draw up Terms of Reference for an agreement between Alcoa, Incra, Acorjuve, and the public prosecutor's offices to assess damages caused by the effects of mining in Juruti. The company begins operations.

August 2009

Incra publishes the Rights in Rem Concession Contract, granting residents of Juruti Velho rights to the territory. This collective title to the land is a milestone in the Ribeirinhos' struggle and formalizes the Juruti Velho Agro-Extractivist Settlement Project.

October 2009

Courts ban Alcoa and its subsidiaries from entering the territory of the Lago Grande Agro-Extractivist Settlement Project and oblige the multinational to respect the communities' right to prior, free, and informed consultation, even for the exploration phase. The company had plans to build a new mine in the region, next to Juruti Velho.

December 2020

On the morning of December 26, 2020, residents of the Jauari community in Juruti Velho go to fish and notice river waters are muddy. They find the mud is coming from the tailings pond in Serra Capiranga, less than 3 kilometers from the community.

April 2021

Residents of Capiranga notice another waterway in the region has taken on a muddy color. A new leak in an Alcoa tailings pond pollutes the Chain River. This is the second case in less than four months, both detected by residents.

May 2021

One month later, Alcoa informs investors in the United States that rains were to blame for the spills and that they were “disputing these fines at the administrative level,” and that the “incidents” were “soil erosion events” that had not “involved or affected bauxite residues [tailings] or impoundments.”

July 2021

Residents of Juruti Velho block truck access to Alcoa's mine, in protest at the tailings spills that occurred between December 2020 and April 2021. Three months later, the company reaches an agreement with Acorjuve, under which the company will provide immediate aid equivalent to four minimum wages per month for a fixed period to families affected by the river pollution.

May 2023

After years in a stalemate over how Alcoa would pay compensation for damages caused by the mine, Acorjuve and federal and state prosecutors agree to $7 million, 60% to be transferred to the families and the rest to be retained by the association for collective projects and organizational costs.

November 2023

After receiving a complaint about Alcoa's intention to build a new mine in Juruti Velho, the Federal Public Prosecutor's Office in Santarém opens an investigation to check whether the multinational is respecting articles from ILO Convention 169, which stipulate that any economic activity affecting a traditional community must have free, prior, and informed consent.

November 2024

Alcoa presents Acorjuve with a proposal to access Serra Uxituba to explore for bauxite. According to the proposal, rejected by community residents, the mining company would pay the association $14,800 to drill 539 holes in the hills.

January 2025

Alcoa files an application to explore for bauxite in a region that overlaps with 1,092 hectares of the Maró Indigenous Territory, in Santarém. After being questioned by SUMAÚMA, the National Mining Agency reduces the area stipulated in Alcoa's exploration license request removing the overlap with the Indigenous Territory.

Swipe right

Swipe right

Indigenous lands in the crosshairs

The Reynolds Metals Company (RMC) did the first geological exploration studies in Juruti Velho in the 1970s, around the same time as the Radam Project, implemented by Brazil’s military-business dictatorship. The company then had two subsidiaries, Mineração São Jorge Ltda and Matapu Sociedade de Mineração Ltda. In the 2000s, all three mining firms were bought by Alcoa, which took over exploration work in Juruti.

The US multinational began its operations in 2009, and since then has extracted 83 million metric tons of ore in Juruti Velho. After leaving the mines, the ore travels 55 kilometers by rail to the company port in Juruti, where it is taken to the Alumar complex aboard ships with a capacity of 55,000 metric tons. Owned by the mining companies Alcoa, South32, and Rio Tinto, Alumar has a refinery and port in São Luís, Maranhão. There, part of the ore remains in Brazil while the rest is sold abroad.

All of this infrastructure relates to a steady demand for raw material. Alcoa and its subsidiaries currently have 38 mining applications on file with the National Mining Company, most for exploration licenses; together, these cover nearly 260,000 hectares, roughly the area of Luxembourg. The three most recent requests for exploration licenses were submitted in January 2025, and one of these is of note: 1,092 hectares of the nearly 8,000 hectares cited in the application actually overlap with the Maró Indigenous Territory, inhabited by the Arapium and Borari peoples, in the municipality of Santarém.

In September 2024, the territory was established under a decree published by the ministry of justice. Article 176 of Brazil’s Constitution of 1988 bans mineral exploration on Indigenous territories until enactment of a law regulating such activities, and no such law exists as yet.

Alcoa did not respond to SUMAÚMA’s questions about the mining application involving the Maró Indigenous Territory.

In a written statement, the National Mining Agency said, “there are no legal restrictions on companies applying for areas in any part of the national territory,” and each request is reviewed individually. But it also said licenses are not granted for Indigenous areas. The Federal Public Prosecutors Office, however, considers this type of application illegal in itself, and argues it is the duty of the federal agency to delete all such submissions from the system. Prosecutor Paulo de Tarso, with the Federal Public Prosecutors Office in Santarém, said his agency intends to open an investigation into the case.

The National Mining Agency sent its statement to SUMAÚMA on April 4. Five days later, the head of the agency division in charge of granting authorizations attached a requirement to Alcoa’s application: a 1,092-hectare area—the same area questioned by SUMAÚMA—must be removed, because “the request presented partial interference with Maró Indigenous Territory.”

Odair José Borari, head cacique of the Maró Indigenous Territory, was surprised to learn that Alcoa has an eye on his community’s land. “Until now, we’ve only had trouble with loggers, not with mining. It’s a surprise to me that their application invades our territory,” the leader said.

In the Serra do Uxituba, where the company wants to open new exploration fronts, the soil bears signs of its Indigenous past. Three archeological sites in the region are registered with Brazil’s Institute of National Historic and Artistic Heritage, Iphan. When residents climb the hills, they often find pieces of old pottery left by peoples who lived in the region, probably Munduruku or Muirapinima. These ceramic shards represent another of the region’s endangered treasures. “These pieces are a record of our history, and there is still much to study about this in the Amazon,” says Indira Amazonas, who was born in Juruti and is working on her master’s in anthropology at the Federal University of Pará.

Riches comes from the Forest

A Flamengo fanatic, Marunei Guerreiro de Mesquita, 54, only takes off one of his 20 T-shirts emblazoned with the name of the Rio de Janeiro soccer club when he dons one from the turtle protection project he has been running for 15 years in Miri Centro, in Juruti Velho. To reach this region, which could also be impacted by Alcoa’s plans, it is necessary to go around the Serra do Uxituba.

Marunei’s father, Osvaldo, was the first to teach him about the importance of preserving the Forest. “He didn’t like to see people cutting down trees. He’d say, ‘Why did you cut down the tree, just to hurt it?’” recalls Marunei, who uses what he learned at home to sound a warning about what could happen to the community and the Turtle Project if Alcoa begins mining in the region: “First off, we’re going to lose our River, because the springs will be affected. That’s the saddest thing,” he says.

“The only good legacy we’ll leave behind, that won’t be erased, is what we do for the community; it’s the conservation work,” says Marunei, who in March released more than 7,000 hatchlings of tracajá, pitiu, and other turtles into the River.

In the Serra do Uxituba, Dona Maria Auta Garcia is also taking part in a turtle preservation project. In addition, she tends to her cassava patch, works with açai, and even fishes from time to time.

“I’m used to hard work,” proclaims Dona Maria as she walks through her garden with us and tells us her children keep insisting she shouldn’t climb into the hills, ever since she saw a jaguar prowling around there.

In 2016, Dona Maria’s family held a puxirum to build a flour mill up in the hills, next to her garden patch. “[We] used to come down with cassava on our backs,” says her husband, João Garcia.

Dona Maria is keen to point out that her husband also cooks, washes up, and irons. She doesn’t miss the electricity when the community generator is turned off at ten p.m. and the lights go out. Is anything at all missing for her in Uxituba? “I don’t think so, just good health,” she says, laughing again. Still, at the age of 69, she climbs into the hills Monday to Friday to tend to her crops. No, there really isn’t anything missing for her in Uxituba—but what is ever-present is the danger the Forest will be destroyed by one of the biggest mining companies in the United States.