‘Divide and conquer’ – Belo Sun’s tactics cause consternation along Xingu river

The Canadian gold mining company is accused of stirring up communal strife and other irregularities in an area already impacted by Belo Monte

By Hyury Potter (text) and João Laet (photos), Xingu River, Altamira, Pará – December 18, 2024

The office at number 1989 on Rua Madre Teresa de Calcutá, in the central region of Altamira, welcomes Ribeirinhos and Indigenous people with smiles and handshakes. Help with “public policies” and “support” for community projects are also on offer. Yet there is a catch. This is the Brazilian headquarters of Belo Sun Mining Corp, a Canadian company that intends, over the next 18 years, to churn through 620 million metric tons of ancestral land in Pará’s Amazon – more than the weight of Rio de Janeiro’s Sugarloaf Mountain – to bring in over US$ 10 billion in revenue from gold that now sits an area inhabited by forest and traditional populations. It isn’t the first time these peoples’ territories and ways of life have been threatened. Now, because of the communities’ abandonment, vulnerability, and fatigue, the company is looking to advance its project – amidst a war of unequal forces.

In Altamira, there has been resistance to mega-projects that have jeopardized the lives of humans, more-than-humans, and the planet for at least 35 years. In February 1989 – at the same address where Belo Sun’s headquarters are located – the city hosted the first Meeting of Xingu Peoples to discuss the impact of a huge federal government project to build hydroelectric plants in the region. This event spawned the famed image of the warrior Tuire Kayapó, who died in August 2024, holding a machete to the cheek of Eletronorte’s director at the time, José Antonio Muniz Lopes, a man with connections to oligarch José Sarney, then the president of Brazil. Eletronorte was the government-run company responsible for the project.

Three decades later, the Belo Monte Dam, one of the hydroelectric plants to come out of the project, was built at a cost of more than R$ 40 billion after nearly ten years of construction. Today, it is directly responsible for sequestering 70% of the water in the Volta Grande region of the Xingu River, 130 kilometers containing vast biodiversity that is home to Indigenous peoples like the Arara and the Yudjá/Juruna, as well as to traditional Ribeirinho communities and smallholders. After the dam was built, making a living from fishing became impossible in some regions, and Ribeirinhos are dealing with this scarcity and depression after being forced to move far from the river. During droughts, the Xingu River, which before was the “road” running through these communities, is also no longer so easily navigable. Nor is there basic sanitation, schooling and adequate healthcare. Many of the promises that “life would improve,” made by the government and Norte Energia, the plant’s concessionaire, were submerged as if they were part of the forest. Local Yudjá/Juruna indigenous people often say Belo Monte ushered in the end of the world.

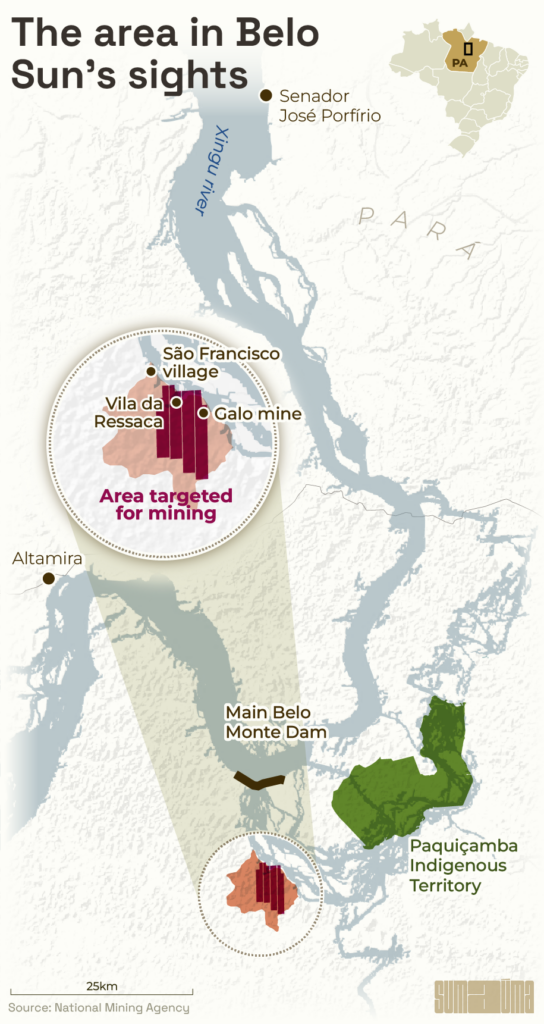

It is in this scenario of destruction, along with the government’s abandonment, that Belo Sun plans to build Brazil’s largest open-pit gold mine. If an environmental license is granted to the mine, two enormous holes, known as mining pits, will be opened in an area where the Amazon Rainforest currently stands. The traditional life of the region’s peoples will be threatened by noise from explosions, earthquakes, dust clouds, construction of new roads, and incessant truck traffic. The project could also be expanded, as the company has 83 mining requests under consideration with the National Mining Agency – spread over 145 kilometers in the Volta Grande region. Not to mention the tailings pond and toxic material used in processing gold – which could contaminate the already-dam-impacted Xingu River. To gain support for this project, the Canadian group is adopting strategies that lead to division in local communities though it starts with smiles, handshakes and “help” for the affected peoples.

“We take part in everything there,” acknowledged Maria Auxiliadora Costa, Belo Sun’s licensing coordinator, summing up the company’s activities in locations where there is a direct interest in opening the gold mine. This participation ranges from “financial support” for local projects to helping the municipal government. According to the mining company representative, “sometimes it’s people who need to be placed in certain public policies,” she said in an air-conditioned room at its Altamira offices, alongside the director, Rodrigo Costa, who is also her husband. The couple gave a lively PowerPoint presentation to SUMAÚMA with general information on the project. There was nothing but smiles until the conversation turned to topics like environmental licensing, allegedly irregular purchases of agrarian reform land, and a failure to adequately recognize original peoples.

This type of “support” the company offers is a common practice used by mining projects around the world, say specialists who have looked into violations committed by transnational companies against traditional Amazon communities.

“What we’ve seen in the Amazon is that groups with foreign investors look for money through projects that would initially be non-viable, but that become viable after taking a series of steps to obtain support from communities, and one of these steps is enticing leaders, even through illegal means sometimes,” says Fernando Soave, a federal prosecutor in Amazonas who has worked in the state for nearly a decade on lawsuits involving mining companies and original peoples. “Unfortunately, in Brazil we don’t have a provision in the Criminal Code for what could be considered a type of private corruption.”

The environmental license for the gold mine project, in which the Canadian company could invest around R$ 1 billion, is pending from Brazil’s environmental agency, Ibama, after ten years of court disputes, conflicts, irregularities, and twists. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has accused the mining company of illegal land purchases, illicit monitoring of residents, and failing to listen to communities. There are also allegations that cattle are being farmed illegally on land coveted by Belo Sun in the Volta Grande region, and communities are being divided so they find it harder to deny the advances of the mine.

The latest twist concerns a community in Belo Sun’s path that has given up resisting. The company denies the irregularities (read more below).

The area of interest for Canada’s Belo Sun, the Volta Grande region has already endured the harsh effects from construction of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant (above). Photo: Lilo Clareto

On the one hand, the plant brought drought to the Volta Grande region, sequestering 70% of the Xingu River’s water; in some stretches, fishers must drag their boats across the rocks. Photo: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

On the other hand, flooding in the area behind the dam killed thousands of trees. Photo: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

Many of the Ribeirinhos who lived along the Xingu’s riverbanks were removed and now reside in Collective Urban Settlements. Photo: Lilo Clareto/Amazônia Real

From resistance to the executive office

In May 2013, construction on the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant was already punishing Altamira with a rise in violence and real estate speculation as a result over 20,000 workers arriving to build the dams. According to data from the Institute of Economic and Applied Research’s Violence Atlas, the number of deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in the city shot up from 12.5 in 2000 to 133.3 in 2017, nearly five times the rate for the city of Rio de Janeiro for this same period.

During this time, according to a report from the Federal Public Defender’s Office and Pará State’s Public Defender’s Office, Belo Sun was allegedly involved in the irregular purchase of areas in the region to make the gold mine feasible. This was when the leaders of São Francisco Village, located on the right bank of the Xingu River, sent a letter to the Indigenous affairs agency, Funai, and to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office asking that 104 hectares of territory be recognized as belonging to the Indigenous people, because of “threats of expulsion from the region by the Belo Sun mining project.”

The document said residents of the village, currently home to 40 Indigenous people, were contacted by “people from the [Belo Sun] company.” The representatives reportedly said they would have to be “removed from the location” because the area “is part of the [mining company’s] project.”

In 2015, the Indigenous agency looked into whether the territory met the requirements to become an Indigenous Territory. Government workers visited the village in 2019 and 2022 to perform interviews and collect more information. They found that the “Juruna of the São Francisco Community vigorously maintain an extensive network of familial relations and of coexistence with their Juruna relatives in the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory and with Arara relatives in the Arara da Volta Grande do Xingu Indigenous Territory,” according to the document.

Also in 2019, the Indigenous affairs agency’s technical staff asked that a working group be formed to carry out an anthropological analysis of São Francisco Village, a stipulation for creating new Indigenous Territories. Five years later, the village’s request remains at a standstill. But not without twists that have surprised employees at the Indigenous affairs agency and the Federal Prosecutor’s Office who have worked on the case.

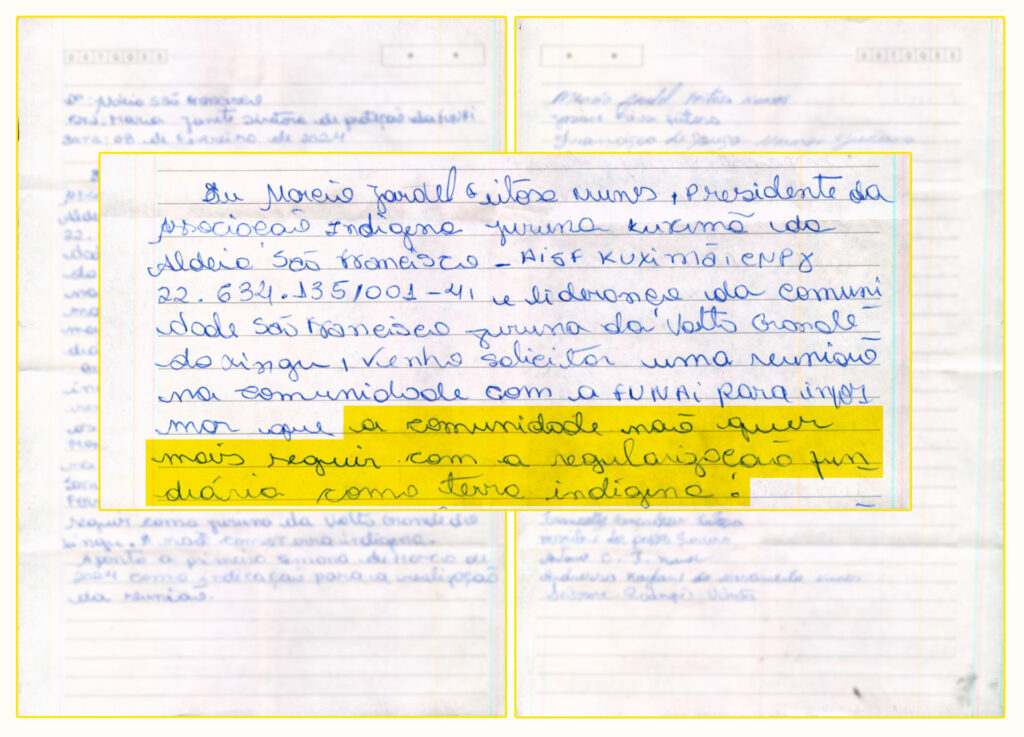

On February 8 of this year, Márcio Jardel Feitosa, the president of the Juruna Kuximã Indigenous Association of São Francisco Village, filed a handwritten letter with Funai, the Indigenous affairs agency, in Altamira: “The community no longer wants to continue to regularize the land as an Indigenous Territory.” The document explains: “We want to strengthen our Indigenous Association and our relationship with the Volta Grande do Xingu relatives and with the Basic Environmental Plans of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant and Belo Sun ventures.” These Basic Environmental Plans are made by the companies and establish compensation when an activity causes environmental and social damage to communities. The letter has one page with a succinct three-paragraph explanation of the village’s new plans and another page with the signatures of 27 local residents.

For Belo Sun, the withdrawal of the request to recognize the area as Indigenous Territory could not have come at a better time. Three months earlier, in November 2023, the mining company was informed of a technical report from Indigenous affairs agency Funai that said licensing for the gold mine would have to wait for the process of creating the São Francisco Village’s territory to be finalized – which could take years. According to an official letter from the federal agency, this measure was necessary because of the company’s plan to “remove the village,” and to “add to studies to include all Indigenous groups subject to impacts by the venture,” as required by national and international law.

The Belo Sun mining company contested the Funai report, but was unable to reverse the agency’s decision. The residents’ withdrawal makes the gold project more feasible – and could spell the end of the community along the Xingu River.

Representatives with Belo Sun told SUMAÚMA that no agreement was made with São Francisco Village’s residents to convince them to back away from seeking recognition as an Indigenous Territory.

The association’s president, Jardel, is the son of the village’s founder, Francisco, and he also signed the first letter – asking for recognition as Indigenous Territory – because he was afraid Belo Sun would expel residents in 2013. Speaking through messages, he also denied there was any kind of prior agreement with the mining company. He explained the decision was made to withdraw the request because of the Indigenous affairs agency’s delay in recognizing the territory, in addition to hardships in the region. According to Jardel, the initiative was taken precisely because the community wanted an “open conversation” with the company and competent agencies. He said the request for recognition has been dragging along for some time, without any measures for demarcation, which is why his people are open to hearing proposals. “The community is tired of waiting,” Jardel said.

The Indigenous affairs agency acknowledges its duty to visit São Francisco Village to investigate the sudden shift in position and talk to residents about the consequences of withdrawing from the process of creating the Indigenous Territory. “Our role is to explain to them what could happen based on the withdrawal. If they were removed to install the mine, there is this possibility that they lose touch with their relatives in the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory and with the Xingu River, since there isn’t a lot of surplus land in the Volta Grande region. This proximity to the river constitutes the Juruna’s very being,” explains Luis Felipe da Silva, the head of Funai’s Environmental and Territorial Management Service in Altamira.

When asked about the delay, da Silva said that to create the new Indigenous Territory, the Indigenous affairs agency needs to draft an Identification and Delimitation Report, something that depends on the creation of a working group at the agency’s offices in Brasília. He says the group has yet to be created because of a high number of requests for recognition of Indigenous Territories (380 in 2013 alone), as well as because of the covid-19 pandemic.

‘Worse than Belo Monte’

At the Belo Sun headquarters in Altamira and at an office in the Vila da Ressaca region, in the municipality of Senador José Porfírio, in the Volta Grande region, the mining company’s representatives claim to serve all residents. Indigenous leaders who spoke with SUMAÚMA say a large company making nice with communities to gain allies seems to be history repeating itself.

“Belo Sun doesn’t open room for discussion with communities, but rather just with the leaders. Even through we filed a collective consultation protocol,” says Bel Juruna, a licensed practical nurse in the Special Indigenous Health District. Bel, one of the main female Indigenous leaders in the Médio Xingu region, spoke with SUMAÚMA from the porch of her home, in Mïratu Village, in Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory, one month after the birth of her fifth child, Aquiles. “They [Belo Sun] come to our door, where there is already no water, where it has already been impacted by another project [Belo Monte]. It seems like there’s going to be an extermination here in the Volta Grande [region]. Not just of the people, but of the entire region. Belo Sun is worse than Belo Monte,” Bel concludes, while rocking her baby in a hammock.

The failure to mandate prior and informed consultation of the Indigenous peoples in certified and de-villaged lands, like the peoples of São Francisco Village, is also the subject of a civil action in the public interest brought by the Federal Public Defender’s Office and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office. Belo Sun says it consulted the peoples in the Volta Grande region about the gold mining project, but the Federal Prosecutor’s Office said this work was “merely primary data collection” that did not comply with International Labour Organization Convention 169, which Brazil has ratified. The consultation mentioned by Belo Sun was done after an advance license was issued, in violation of the peoples’ rights “to truly participate in and influence the decision-making process,” the prosecutors argued, citing a decision by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on this topic.

Bel points to the lack of transparency in the company’s negotiations with community leaders as one concern. She was a direct participant in drafting the protocol on consulting the Juruna people, but she says it is not being fulfilled.

Cacique Gilliarde, Mïratu Village’s leader, is another resident in the Volta Grande region who was initially opposed to the mining company but changed his position in recent months. “I think we prepared ourselves. We believe that if another project comes, the conditions must be met even before the project happens, unlike what happened with Belo Monte,” the cacique says. “I think in the beginning Belo Sun wanted to trample us, not put us on the inside; now we were consulted, heard, and we made our proposals,” says Giliarde. He declined to share more details.

Researcher Elielson Silva, with the Rural Federal University of the Amazon, has spent seven years studying how Belo Sun operates and he describes the company’s tactics as follows: “What they want is to divide [communities] to conquer [territory],” he says. “The violence practiced in the Volta Grande [region] is infrastructural and affects various areas, from attempting to coopt local leaders to pressuring researchers. None of this is random, they are capture tactics,” the professor adds, referring to the company line of “developing the region” to obtain support from the communities.

Elielson is a researcher with the New Social Cartography of the Amazon Project and he was one of the scientists blocked from holding a November 2017 seminar at the Federal University of Pará on Belo Sun’s impacts on the Volta Grande region, as the result of a protest led by Dirceu Biancardi, the Christian Social Party mayor of Senador José Porfírio, the municipality where the mine will be installed if environmental regulator Ibama approves the environmental license.

“They locked us in the auditorium and shouted that we were against development in the region,” the researcher recalls, pointing out that this type of intimidation reaches Indigenous and Ribeirinho peoples in a much more violent way. “There are cases of residents who oppose the mining project who have had to leave the communities because of threats,” he says.

Dirceu Biancardi did not respond when contacted by e-mail. Belo Sun did not comment on the incident.

Divisions are also apparent in Vila da Ressaca, the Ribeirinho community that sits along the banks of the Xingu River and that, around two kilometers from one of the planned mines in the mining company’s project, will be directly affected if Belo Sun moves forward. The Canadian mining company is gaining more supporters there with the strategy of “helping” leaders.

Cleia Juruna is the president of the Juruara Association, whose members are Indigenous Juruara and Arara living in Vila da Ressaca. She is another leader who has changed her mind about Belo Sun in recent years. The organization’s offices are a short five-minute walk from her house. The brief journey is made in part on walkways raised a few centimeters from the ground, enough to keep pedestrians from stepping in open puddles of sewage. There is no basic sanitation.

The association sits next to the Belo Sun offices in Vila da Ressaca and was created in 2020 with the Canadian mining company’s support. Talking about Belo Monte’s impacts on the area, Cleia Juruna calls the power plant, whose name translates to Fine Mountain, a “Fine Monster.” From the veranda of her home, she talks about how the infrastructure in the region, home to around 100 families, is still precarious and water sometimes runs out. “Lots of people returned to Vila da Ressaca because they want the indemnity and reallocation the mining company can offer,” says Cleia. She says that now they are more hardened to dealing with large corporations, after so many problems with Norte Energia, the hydroelectric plant’s operator. “Because now it’s as if we’ve been once bitten. Now we won’t wait anymore. Now we have somewhere to run. If the company says it will do something, we know how to claim our rights.”

In an interview with SUMAÚMA, the mining company’s representatives confirmed they had provided “infrastructure” and “legal” support for the association’s facilities. According to the company, these actions are a way of “empowering” the communities.

Academics researching the impact of large mining companies on the Amazon disagree. “Studies show that companies build ties with leaders, offering advantages, and end up dividing communities. What we see in practice is that protocols on consulting the peoples are not followed,” explains Fernanda Bragato, a professor at Vale dos Sinos University, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. He has been following the legal defense of the Indigenous Mura people, in the state of Amazonas, who are the targets of an exploration project by mining company Brazil Potash, which also operates under the Potássio do Brasil name, and has already been reported to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for hiding information from investors on Indigenous populations impacted by the project, the same charge leveled against Belo Sun before the Ontario Securities Commission.

The similarities between the Belo Sun mining company and Brazil Potash don’t stop at how they are gaining supporters within the Amazon’s traditional communities. At least in official documents, the two companies have received investments from Canadian group Forbes & Manhattan – a billion-dollar fund that raises money on stock exchanges and invests in projects that can earn a profit.

Nevertheless, in an interview with SUMAÚMA, Rodrigo Costa, the director of Belo Sun, said that “in the past the mining company belonged to the Forbes & Manhattan group, but it no longer does today.” Since May 2022, Belo Sun has not been a part of the fund’s portfolio of companies; however, reports submitted to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in October show the billionaire fund’s executives still work for both mining companies.

Contacted by e-mail, the Forbes & Manhattan group did not respond.

Illegal concession and purchase of lands

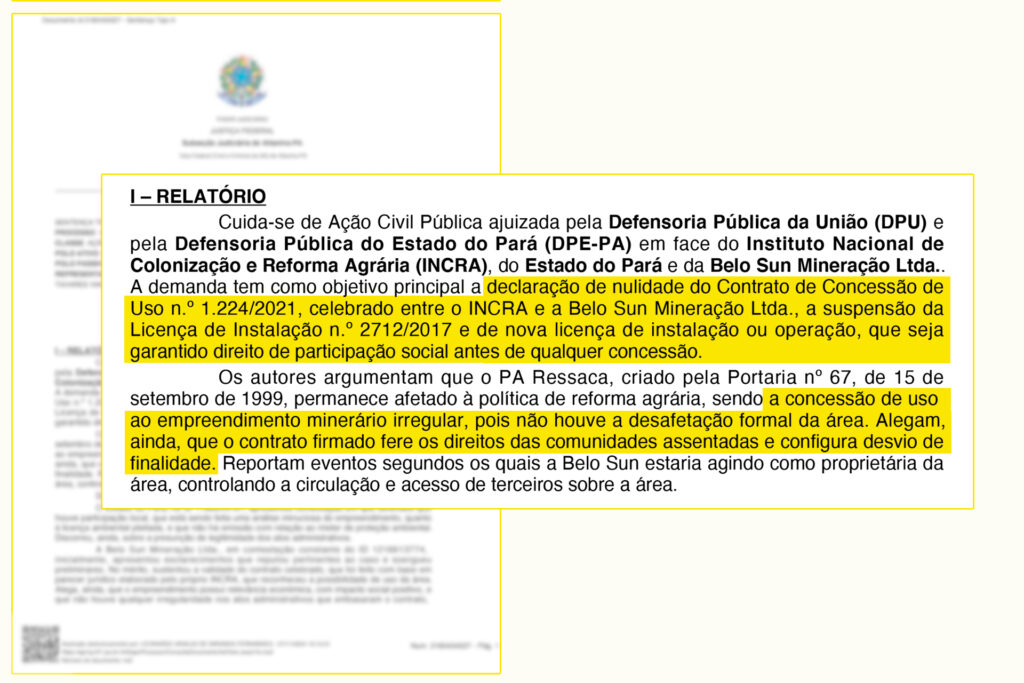

It was in this scenario and taking advantage of the vulnerability created in Volta Grande communities by the Belo Monte Dam that, according to the Federal Public Defender’s Office, the company allegedly made illegal purchases, from 2012 to 2016, of lots in an agrarian reform settlement created in the 1990s, to establish its headquarters and make “space” for the future gold mine. At least 21 lots belonging to families who were settled in the Ressaca Settlement Project, in the municipality of Senador José Porfírio, were sold to Belo Sun at prices of up to R$ 1 million, according to documents published by Estadão. The Federal Public Defender’s Office suspects the transaction is illegal because of the legal restrictions people are under when they receive agrarian reform land. This type of maneuver in agrarian reform settlements has been standard practice for large companies operating in the Amazon and is exemplified by US-based Cargill, in Abaetetuba, and by Vale, in Carajás, as reported by SUMAÚMA through the Unsustainable project.

After purchasing 2,428 hectares in the Volta Grande region (an area eight times the size of Rio de Janeiro’s Ipanema neighborhood), the mining company then tried to receive permission from the government agency responsible for agrarian reform, Incra, to mine some of the territory occupied by smallholders. It was received during the far-right administration of Jair Bolsonaro. That was how in November 2021, Incra’s president at the time, Geraldo José da Camara Ferreira de Melo Filho, signed a concession agreement with the company for “mining exploration.” At the time, officers said there was no provision in the agency’s administrative rules for this type of concession. It was only a month later that the government published a Normative Instruction allowing mining ventures to receive concessions on land designated for agrarian reform. It happened after the then vice president, Hamilton Mourão, a retired general, met with a member of the Forbes & Manhattan group and Belo Sun representatives, at the Mines and Energy Ministry, as reported by Agência Pública.

The Canadian group had long coveted the concession. Danilo Hoodson, an agriculture technician who worked at agrarian reform agency Incra for 18 years and led the Altamira office from 2013 to 2017, remembers the mining company’s insistent requests. “I remember at least two occasions when the mining company’s representatives showed up with draft agreements drawn up, with my name already on them, just needing my signature. But of course I didn’t sign.”

“Not only was there no administrative provision [at the time] for this type of concession, but the company’s compensation was well below the land’s value,” Hoodson says.

A few months later, the Federal and State Public Defender’s Offices filed a civil action in the public interest asking to void the concession agreement to use the land because of the “illegal purchase of lots,” illegal monitoring of residents, as well as an error in the size of the area impacted by the Belo Sun project, which should be 4,131 hectares – and not the 2,428 hectares stated in the agreement.

In 2023, the Agrarian Development Ministry, under which land reform agency Incra operates, added to the chorus of agencies performing investigations, recommending that it void the Belo Sun concession and revoke the Normative Instruction. These would be “essential measures for pacification and conflict resolution in the area of the Ressaca Settlement Project, Ituna Parcel, and surrounding area.” The agency nevertheless ignored this recommendation and kept the agreement intact.

On November 27, 2024, a Federal Court ruling voided the concession agreement made with Belo Sun, saying Incra “modified the designation of public property,” creating “a precedent wherein the agrarian reform policy is exposed to social and economic pressures.”

SUMAÚMA contacted Incra twice for comment on the Belo Sun concession agreement. Prior to the court’s ruling, the federal agency had responded that the agreement “was signed in December 2021, based on the rules in effect under the scope of Incra.” However, the date of signature on the document is November 26, nearly one month before the rule change to permit mining activities in settlement areas, as previously stated. On December 3, SUMAÚMA once again asked Incra about the agreement, with the agency replying that it had not yet been notified of the ruling.

In a statement published on Belo Sun mining company’s website, its president, Ayesha Hira, said the company is “evaluating all the legal options available” and that it is looking “forward to working with Incra on the next steps.” She also added: “We continue to work to benefit the region and all stakeholders as we look to advance [the Volta Grande Project].”

Despite the court ruling to void the agreement, the territory that was allegedly illegally ceded to the mining company is still being disputed. In June 2022, rural workers occupied part of the land given to Belo Sun and created a rural settlement there. The company lodged a complaint with Pará’s Court of Appeals against the settlers, as well as against environmental non-governmental organizations as a result of this occupation.

SUMAÚMA asked Belo Sun about the accusations, but the company did not respond. The mining company did, however, answer the courts in July 2022, denying any illegality in purchasing the lots and in executing the agreement with Incra.

Intimidating monitoring

The illegal monitoring of the residents that the lawsuit mentions is familiar in the Volta Grande region. In 2022, researchers at both the Higher Amazonian Studies Center at the Federal University of Pará and Maranhão State University reported how the security company contracted by Belo Sun uses an “intimidating approach” with residents in the Ressaca Settlement Project.

“During field studies, armed security personnel connected to ‘property security’ were seen performing continuous patrols on ‘side roads,’ imposing extralegal rules, restricting free movement, preventing access to commonly and traditionally used areas, entering areas that have no connection to the mining company in an authoritarian manner, intimidating passers-by, and keeping watch, patrolling social life,” reads the document attached to the suit.

Attorney Diogo Cabral, who is defending the residents of settlements that have been taken to court by Belo Sun, says he is very familiar with the mining company’s monitoring. “It’s normal to see the company’s security team’s car near meeting locations. It’s a form of intimidation,” Cabral says.

SUMAÚMA’s team was not approached while traveling around the region on September 24, but the next morning, Maria Auxiliadora Costa, Belo Sun’s licensing coordinator, sent a message to a local member of the team that said that they had “heard a group of journalists passed through and would like to talk about the project.”

Belo Sun denied it was monitoring residents. Rodrigo Costa, the company’s director, told SUMAÚMA that the security company is “essentially focused on prospectors,” to prevent intrusions by miners who use heavy machinery.

‘Enigmatic’ cattle

Despite the presence of the company’s security personnel in the region, a cattle herd appeared on the land Incra had ceded to Belo Sun without the mining company’s knowledge, according to official statements. A report submitted in May of this year to environmental agency Ibama said there were around 1,000 head of cattle in the Ressaca Settlement Project and alleged that the cattle were from illegal farms targeted by an operation to remove intruders from the Ituna/Itatá Indigenous Territory. Ibama agents found the animals when they visited the Volta Grande region on May 27. They asked the company to provide clarifications, since Belo Sun “is not registered in the Pará State Agriculture System, which prevents it from having a cattle herd,” according to the document obtained by SUMAÚMA.

The mining company sent a response to Ibama on June 12, through its legal team, accusing “opportunists in the region of placing cattle herds [in the area] inappropriately and without company authorization” and saying “Belo Sun does not have police power to remove any person or animal present in the area.”

However, the response from the company’s attorneys contradicts what three Ibama agents reportedly heard on June 28. When they visited the mining company’s headquarters to deliver the cattle notice, they spoke with Maria Auxiliadora Costa, who allegedly said there was a lease agreement to allow cattle in the location. “She even looked for the document right in front of us, but didn’t find it and said that later she would send a formal company response,” Givanildo Lima, one of the Ibama agents carrying out enforcement activities, told SUMAÚMA.

Because the concession agreement granted by Incra is specific to mining, any other type of land designation could be a violation of the agreement, as specified by an item in the contract covering causes for termination.

Director Rodrigo Costa and coordinator Maria Auxiliadora reiterated to SUMAÚMA that the company was not responsible and did not know about the cattle until they were notified by Ibama. They said they executed “bailment agreements” authorizing old residents of the region to remain, from 2012 to 2015. Maria Auxiliadora also said “none of this is valid anymore today” and that the company does not have any kind of cattle lease agreement.

Incra did not respond when asked about the illegal cattle.

In September, when SUMAÚMA was at the location ceded by Incra, near Vila da Ressaca, the cattle had been removed. Residents in the neighboring settlement reported this had happened around two months earlier, right after Ibama notified the company.

In addition to the mysterious cattle, Belo Sun’s area of interest is home to illegal mining operations run by the region’s residents. SUMAÚMA visited the Galo mine, where gold is embedded in the rocks, not mixed with surface mud.

The mine, opened in the 1970s, is reached by traveling along a steep stone and dirt road, along which sits several abandoned homes. The workers who dare to go there now try to extract gold from tailings left from past mining.

“You can get 10 grams a month per person,” calculate the illegal miners who spoke with SUMAÚMA. A gram of gold on the international market is worth R$ 531, but this can vary according to the mine’s situation. They all wished to remain anonymous, since this mining is illegal.

The illegal Galo mine sits in an area covered by one of the mining processes that belongs to Belo Sun. Without an environmental license from Ibama, the Canadian company is unable to get authorization for the mine; yet the illegal miners said they have a verbal agreement with the mining company, confirmed by its director, Rodrigo Costa, to reuse the tailings without using heavy machinery.

In 2023, Ibama and the Federal Police carried out operations at the Galo mine and at other illegal mining operations in the region. Some machinery was burned.

In the last 10 years, various lawsuits have been brought against Belo Sun in the federal and state courts. One of the first questioned the environmental license granted by the state agency, the Pará State Office of the Environment Secretary, in 2013. Because it affects Indigenous land, licensing must be federal and, therefore, granted by Ibama.

Belo Sun's losses in court

The ups and downs of a mining project that, despite not being operational yet, is already damaging communities in the Volta Grande region

2012

Canadian mining company Belo Sun requests an environmental license from Pará’s State Office of the Environment Secretary to drill in the Volta Grande region and create Brazil's largest open-pit gold mine

2013/May

Indigenous peoples from São Francisco Village, residing in the area desired, sent a letter to Indigenous affairs agency Funai asking for the area to be recognized as Indigenous Territory – to prevent their removal from the location

2013/Dec

Pará's Office of the Environment Secretary grants an advance license (the first step in environmental licensing) to Belo Sun

2014/Jun

The federal courts rule in favor of a Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office request to suspend the advance license, ordering a consultation of the Indigenous people affected

2014/Aug

The Federal Public Prosecutor's Office files a civil action in the public interest to ask that environmental licensing be granted by the federal authority (Ibama) rather than by the state's environment secretary

2017

The State Office of the Environment Secretary grants a license to the Belo Sun mine, but this authorization is suspended by the federal courts

2018/Ap

Belo Sun is reported to the UN by Human Rights organizations, who say residents and environmentalists opposed to the project were threatened

2018/Sep

A federal judge granted a Federal Public Prosecutor's Office request to suspend all Belo Sun activities until an environmental license is received from Ibama

2020/Feb

The mining company submitted social and environmental impact studies on the project in the Paquiçamba, Arara da Volta Grande do Xingu, and Ituna Itatá Indigenous Territories. Studies requested by the Juruna were not done

2021/Nov

The president of agrarian reform agency Incra signs a concession agreement for 2,428 hectares located inside of an agrarian reform settlement for Belo Sun to carry out “mining exploration” – despite having no legal provision for it

2021/Dec

Incra issues a Normative Instruction adding “mining ventures” to projects that qualify for inclusion in concession agreements for agrarian reform-designated areas. Signs emerge that Belo Sun may have made illegal land purchases in the region from 2012 to 2016

2022/Apr

The Public Defender's Office sues to void the contract with Incra

2022/May

A state court in Altamira suspends the environmental license issued to the company by the Office of the Environment Secretary until a social and environmental study on Ribeirinhos in the region is done

2023/Sep

The First Region Federal Appellate Court rules that the mine's environmental license falls under federal (Ibama) authority, voiding licenses issued by the State Office of the Environment Secretary

2023/Oct

Funai notifies the mining company that licensing for the mine must await finalization of the process recognizing São Francisco Village as an Indigenous Territory – which could take years

2024/Feb

Leaders in São Francisco Village submit a letter to Indigenous affairs agency Funai to say that the “community no longer wants to continue to regularize the land as an Indigenous Territory” because they want to “strengthen” relations with the “Belo Sun venture”

2024/Nov

A federal court in Altamira voids the mining concession agreement made between Incra and Belo Sun, saying the federal agency “modified the designation of public property

Swipe right

Swipe right

Sources: Funai, Federal Public Defender's Office, Federal Public Prosecutor's Office, Xingu Vivo, Conectas, Ibama, Office of the Environment Secretary of Pará, Pará Court of Appeals, Federal Courts

In 2023, the Regional Federal Appellate Court of the First Region confirmed the project’s license should be issued by Ibama, whose assessment remains pending.

When asked, the Office of the Environment Secretary of Pará did not comment.

One of the few people still resisting Belo Sun mining company’s climate-controlled office, Bel Juruna says she would rather think of her child, slumbering in the rocking hammock on the porch of her home, than imagine the money the gold could bring. “Everything ends. Material goods end, money runs out. So, this decision is on us today to guarantee the future of these children in the next generations,” she says.

The deputy leader of Mïratu village, Diel Juruna, 32, fears for her people’s future. The Juruna are also known as the Yudjá, a word that means “the river’s owners.” If Belo Monte brought the end of the world, the struggle now is to prevent the world from ending again. “If we don’t take measures, a few years from now our children and grandchildren won’t know what our people’s culture is anymore,” he says. The Xingu is Yudjá. And the Yudjá are the Xingu. But the waters have already begun to run dry.

Different companies, similar threats

What can the history of Belo Monte teach the resident’s of the Volta Grande region about the risks posed by Belo Sun?

By Hyury Potter (text) and João Laet (photos), Altamira

If São Francisco Village chooses to negotiate with Belo Sun and ends up leaving the Volta Grande region, it wouldn’t be the first time that Ribeirinhos lost touch with the Xingu River, which is fundamental to their way of life.

At least 260 Ribeirinho families were removed from their homes because of the Belo Monte Dam and were forced to live far from the river that had given them life – and peace. Today, many of them are living in cities in the region.

Back in 2012, the 67 families of Vila Santo Antônio were the first to experience this trauma of being removed from their homes. Elio Alves da Silva, 69, was the president of the community’s residents’ association. He says that instead of proposing a joint solution for the entire community, Belo Monte’s concessionaire chose to hold individual negotiations – which ended up leading to division between residents. “They gave you the money and the family had 24 hours to vacate. Many agreed and now nearly all of the town’s past residents live in different locations. The community ended,” Elio laments. “It was little money, but we didn’t care because there was joy in the town”, says Elio, who now lives off of retirement payments and income from the fish he catches in an artificial lake in Altamira. When talking about his old fishing colleagues, he says many became depressed after being forced to live far from the river.

Those who managed to remain near the Xingu River went on to have a “harder life,” as Jardel mentioned, in São Francisco Village. There are almost no fish to eat and many have deformities. Areas that used to bespawning grounds have become egg cemeteries. Even the ornamental fish that the Ribeirinhos sold for subsistence have seen their populations reduced. Beyond the impact on aquatic animals, changes in the hydrological rates on the Xingu have brought another problem to the peoples in the Volta Grande region: a lack of mobility. If before the Indigenous peoples in the villages in the Trincheira/Bacajá Indigenous Territory took six hours to travel to the city by boat, now, with the river dry, the trip is no longer feasible because of the many rock outcrops along the way.

The roads became the most viable option, but for this they need fuel, which is supplied by Norte Energia – the company that owns the concession to the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant. Since 2015, the concessionaire has given allotments of fuel to villages in the Volta Grande region, the result of an agreement made with the peoples, which establishes the benefit until 2045.

Yet in September, the Indigenous peoples of the Volta Grande region were surprised by a notification from Norte Energia ending the supply of fuel. Protests by the Xikrin, Arara and Yudjá/Juruna peoplesblocked the Trans-Amazonian Highway and the avenue accessing the airport in Altamira. They also occupied the headquarters of the Indigenous affairs agency, Funai, for a few days.

“The Bacajá River, that we used to get around, is dead,” explains Kataprore Xikrin, the leader of Mrotidjãm village and the president of the Bebô Xikrin do Bacajá Association. Kataprore helped to translate the interview with Nhakmaiti Xikrin. Ever with a machete in hand, the warrior with a determined demeanor didn’t let Norte Energia’s representatives intimidate her at a meeting held over video at Funai’s headquarters in Altamira. Speaking in Mebêngôkre, she stood up in the auditorium and complained of the company’s contempt for her people. The next day, she stood firm in the Amazonian sun of Altamira during protests against the company. “We have the right to demand what they took from us. This is my fight,” she said during a blockade of the entrance to the airport.

In a statement sent by e-mail, Norte Energia said the supply of fuel “was discussed and resolved during a recent meeting in Altamira with Indigenous leaders, Funai, the Indigenous Peoples Ministry, and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office.” The statement does not mention the result of the meeting, but sources at Indigenous affairs agency Funai said fuel should only be supplied for two more years.

Anthropologist Thais Mantovanelli, an analyst at Instituto Socioambiental, followed the protests and saw that the concessionaire installed iron gates in front of the company’s headquarters in Altamira two days before the protests. It is, the anthropologist notes, quite a different attitude from the one the company had in 2015, the year the license to operate was issued. “During the project, Norte Energia made various parallel agreements with the Indigenous people, they had a space at headquarters just to serve them. It was like a service desk. Today you can’t even get in there,” Mantovanelli says. Once the protests were over, the company removed the gates.